The three-day conference was headlined by lawmakers, diplomats and rabbis from around the world

The legacy of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—whose 120th anniversary of birth will be marked on April 12, wasn’t taken for granted by pundits and academics in the period following his passing in 1994. Sociologists and religion experts predicted that the Chabad-Lubavitch movement would hemorrhage and dissolve.

In reality, as the three-day Washington, D.C., conference showcased, the Rebbe’s impact on generations of Jews and non-Jews alike has never been felt more.

The event drew almost 300 legislators, diplomats and rabbis, including 25 members of Congress from both sides of the aisle—a novelty in today’s partisan politics.

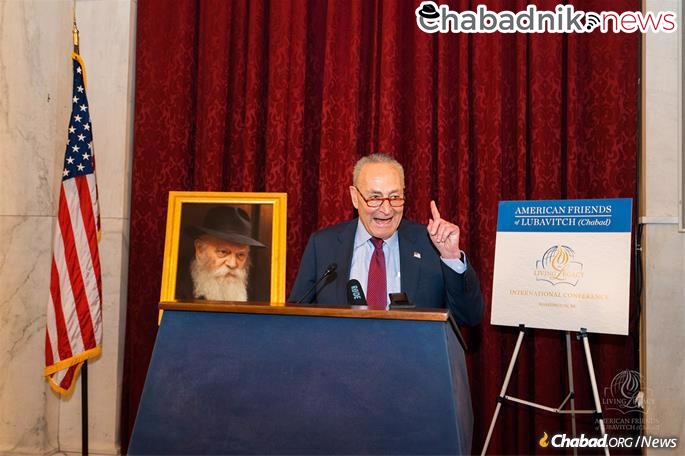

The conference, titled “Living Legacy,” ran from March 29 to March 31, under the umbrella of American Friends of Lubavitch (Chabad). Featured presenters included former Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman, Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer and Western Australia Supreme Court Justice Rabbi Hon. Marcus Solomon.

Like Moses when he reached 120 years, and the Torah attests that “ … His eye had not dimmed … ,” Lieberman declared that the Rebbe’s influence has not waned after 120 years. “Because of the work of the shluchim and because of the followers that you have gained, in some real sense, the Rebbe and certainly his vision, his leadership is still alive and he will go on living well beyond 120.”

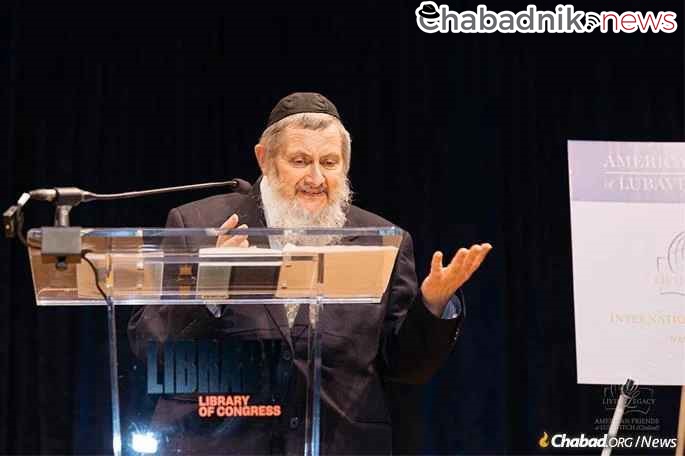

Solomon’s life story demonstrates the impact the Rebbe had on a young teenager, on the remote Perth, Western Australia Jewish community, where Solomon is a rabbi, and on the Western Australia Supreme Court, where Solomon says he would have never been if not for the Rebbe’s personal guidance. Noting how it usually isn’t advised to begin a speech about someone else’s greatness by speaking about oneself, in this case, Solomon told the conference at a lecture held at the Library of Congress, “I can think of no more effective way to convey the depth of feeling and the breadth of admiration for the vision and the leadership of the man that this conference celebrates—Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Rebbe.”

Solomon, an ordained and practicing rabbi is a graduate of Chabad-Lubavitch yeshivahs in Australia, Israel and Brooklyn, N.Y. Alongside that, after a successful legal career in Perth, he was appointed as a justice on the Supreme Court of Western Australia, the first observant Jew to serve in that role. The two paths, he acknowledged, are “in isolation, quite uninteresting. It is the combination that appears to inspire some interest—a combination which I believe would not likely have happened without the radical vision of Rabbi Schneerson.”

Solomon delivered a lecture on the Rebbe’s approach to Judaism’s contribution to the values and morals of a secular country. Explaining the conventional stance of the American Jewish community, whose zealous rejection of religious involvement in the public sphere was rooted in centuries of religious persecution in Europe, Solomon presented the Rebbe’s position.

The Rebbe, he explained, “who rejected the conventional and perfectly understandable stance of the Jewish community, was a man who himself was a product of European Jewry—the very community that for centuries had suffered so horrifically from the failure to separate the exercise of state power from religious doctrine, and a man and whose own world and family had been the brutalized victims of state discrimination against his religious community.”

How, asked the justice, could the Rebbe champion the dilution of the apparently sacred divide between church and state?

The Rebbe’s focus, Solomon said, was not only the Jewish people but humanity at large.

“The Rebbe was more concerned with the threat to humanity of rampant materialism—of the corrosion of community through a G‑dless individualism—than he was concerned by the threat to the Jewish people from a government’s benign endorsement of religious symbols and principles,” Solomon opined. “The Rebbe perceived a far greater danger to society in suppressing the expression of faith from the public sphere than in giving a public civic voice to religious belief.”

As Rabbi Dr. Naftali Loewenthal, an acclaimed scholar of Chassidic thought, put it: “The Rebbe’s goal was that we should all be educators, and in a positive sense, we should all be leaders.”

That concern for the wider community expresses itself in a variety of arenas, as Stuart E. Eizenstat, a career diplomat and currently chairman of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council, highlighted, praising Chabad’s humanitarian work around the world in times of crisis. Eizenstat pointed to Ukraine—where the Rebbe was born, in Nikolaev (Mykolayiv)—where Chabad has spirited more than 35,000 people out of the country and set up refugee camps and shelters throughout Europe.

Schumer, the Senate Minority Leader, spoke of his long-standing relationship with the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and his efforts to posthumously award the Rebbe the Congressional Gold Medal in 1994. “When I was a congressman and not yet a senator,” he told the audience, “I was honored to be a lead sponsor in awarding the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rabbi Menachem Scheerson, of blessed memory, with the Congressional Gold Medal, in recognition of his outstanding work.”

Texas Sen. Ted Cruz said he was “honored to be here to recognize and reflect on the legacy of the Rebbe. I am grateful to stand with the Jewish people. I am inspired by your courage. I am inspired by your steadfastness.”