Thousands of manuscripts at Chabad-Lubavitch Library now readily available to the public

In a move that is making waves in academic and lay circles, the Chabad-Lubavitch Library has created a new site with high-quality, full-color scans of a vast collection of thousands of precious manuscripts that have never been seen by the public—until now. Overnight, scholars and enthusiasts have been poring over the rich content, examining page after page, and sharing their thrilling discoveries with the public.

“The Chabad Library holds one of the richest collections of Judaica in the world, including many thousands of rare books and manuscripts,” says Elly Moseson, visiting professor in Eastern European Jewish Studies at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and an expert on the history and literature of the Chassidic movement, explaining the significance of this moment.

It’s another step for the library that had already gone above and beyond in their efforts to make the collection accessible, Moseson tells Chabad.org. “The library had already revolutionized Jewish learning and scholarship with its digitization and online publication [in partnership with Hebrew Books] of thousands of rare titles from its collection of printed books,” says Moseson.

“This collection contains almost 3,000 volumes of manuscripts,” says Rabbi Shalom Dovber Levine, the library’s director. Levine says this digitized collection will allow students to look back to the source manuscripts of the works they are studying, to resolve questions in the text and correct printing errors.

Some precious artifacts in the new collection have broad appeal, such as the siddur (“prayerbook”) of the saintly Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Chassidic movement, known simply as the Baal Shem Tov or “Master of the Good Name.” “Even non-specialists will be interested in perusing such precious items as the siddur used by the Baal Shem Tov,” says Moseson.

A Vast Archive Precious Books, Photographs and Documents

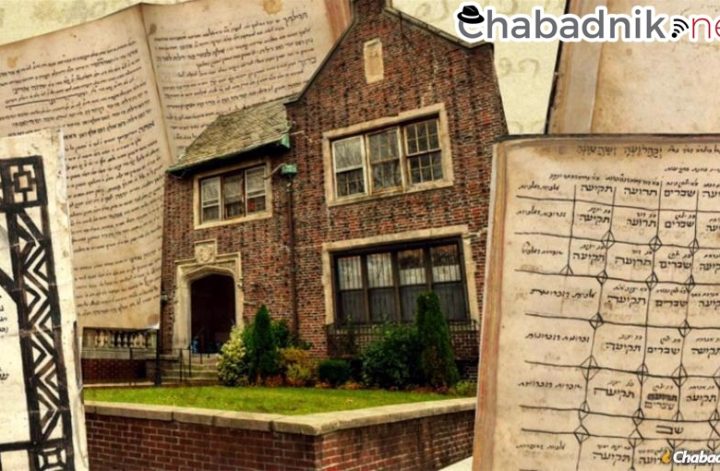

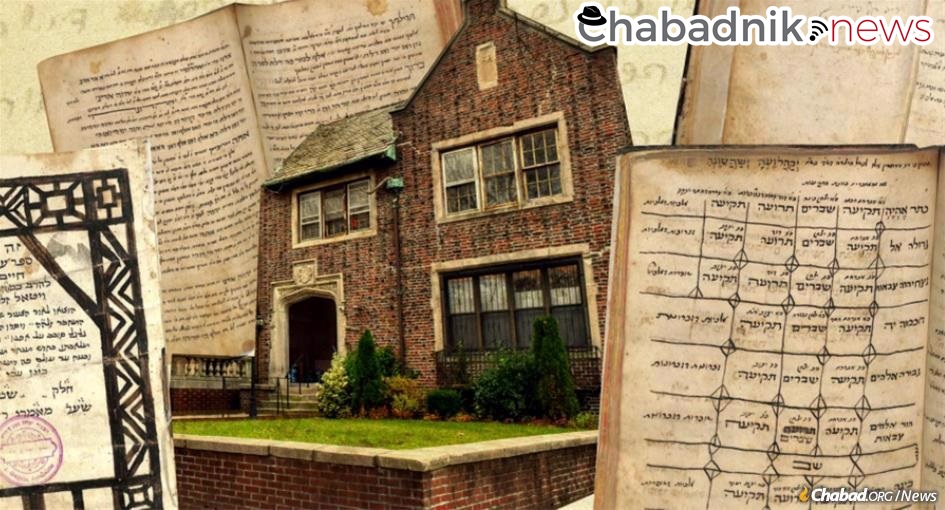

Located adjacent to the iconic tri-peaked facade that occupies 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad headquarters in Brooklyn, N.Y., the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad has long been a haven for researchers, bibliophiles and history enthusiasts. Housing one of the largest Judaica collections in the world, the library always made its extensive print collection available to the public, whether in its reading room or by using their website to browse through some of their 300,000 books or vast archives of photographs and other documents.

It’s not common for a private library to give such unfettered public access to their troves, acknowledges Michelle Margolis, librarian for Jewish Studies at Columbia University Libraries and vice president of the Association of Jewish Libraries. “I’m excited. The digitization of a private library is the exception rather than the rule,” she says. “Putting it all online in a clear way will allow more people to engage with the materials; it’s a really important step.”

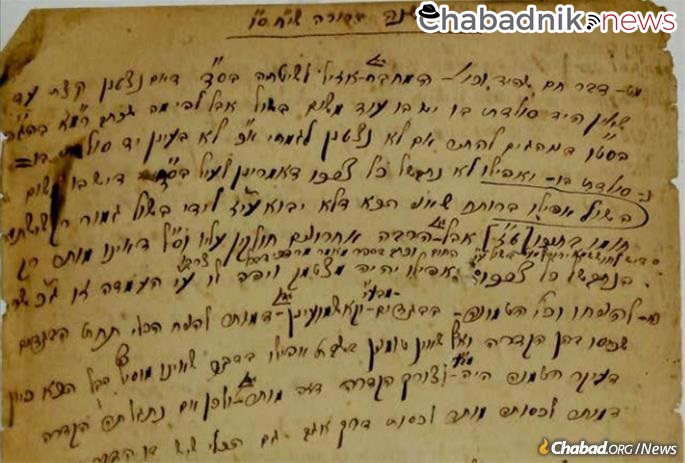

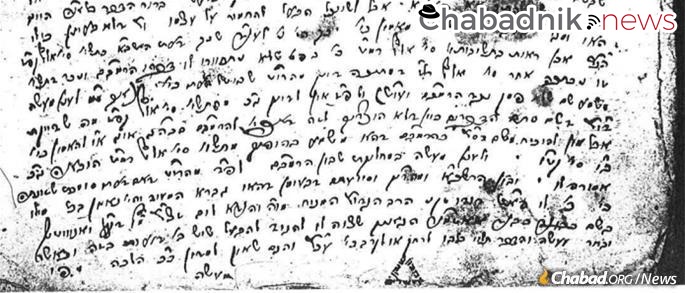

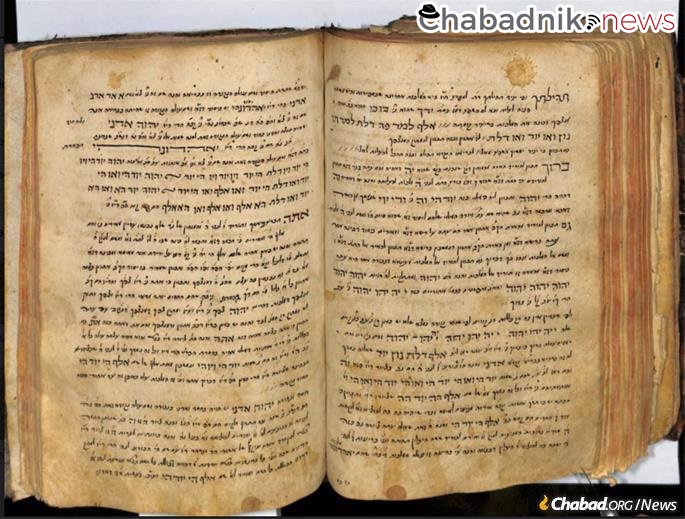

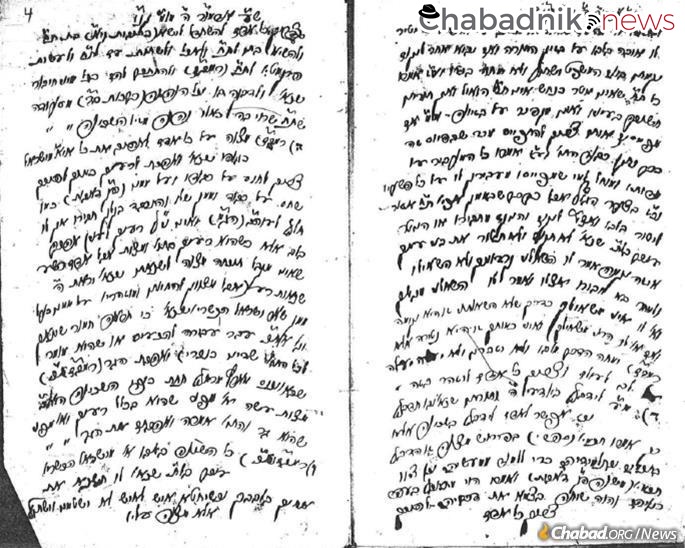

For Moseson, one item that stands out has been hidden from the public eye for centuries, with few ever laying eyes upon it: the siddur(“prayer book”) of the saintly Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov. This priceless manuscript, believed to have been written by the Baal Shem Tov’s brother-in-law, Rabbi Gershon of Kuty (Kitov), has been treasured for generations for its holiness.

The siddur offers us a glimpse into the Baal Shem Tov’s prayer experience, with lofty kabbalistic intentions inscribed within its pages, and his blood and tears staining the Rosh Hashanah prayers.

One of its most striking features are the many names that the Baal Shem Tov’s disciples and their family members wrote in the prayerbook’s margins, with requests that the Baal Shem Tov beseech G‑d on their behalf during his prayers. Names of men and women are inscribed for a variety of blessings, ranging from spiritual needs to blessings for healthy children, and for one woman, “so that she doesn’t miscarry.” “Pray for Chaim the son of Devorah and his wife Chana the daughter of Kreina to be blessed with children,” reads one supplication. Another student asks that his teacher pray for him “to be taken out of the diaspora and to ascend to the Holy Land imminently.” A note written on behalf of the famed Chassidic master Rabbi Yechiel Michel of Zlotchov asks the Baal Shem Tov to “remember” him, and his wife and daughter, in prayer, “that G‑d strengthen his heart to serve Him, and may his children live.”

The story of the siddur’s travails are cloaked in mystery, but what is known is that the Baal Shem Tov’s grandson, Rabbi Yisrael “the Silent,” inherited the siddur from his father, Rabbi Tzvi, the Baal Shem Tov’s only son. During one of Rabbi Yisrael the Silent’s journeys, he stopped in the village of Yarivitch (Yurovichi, Belarus), where he suddenly fell ill. The Baal Shem Tov’s grandson knew his death was imminent and summoned the village’s community leaders, telling them about the precious siddur he had with him. He then requested that they pass the holy artifact to Rabbi Mordechai of Chernobyl (1770-1837). Rabbi Yisrael the Silent passed away, and after burying him, the community representatives traveled to Chernobyl. “We have the Baal Shem Tov’s siddur,” they informed the tzadik, saying they’d give it to him only on the condition he spent a Shabbat with them in Yarivitch. Rabbi Mordechai acquiesced, and the siddur was his.

Somehow, the siddur came into the possession of a wealthy man, Rabbi Yitzchak Lipson, possibly by inheritance. He had it for years, but sometime in the 1920s sold it to the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, who was also a descendant of Rabbi Mordechai of Chernobyl. The Sixth Rebbe brought this priceless possession with him to New York after escaping Nazi-occupied Europe and it was kept in his library. Though portions of it have been reproduced in the past, the siddur’s digitization as part of the Chabad Library’s project marks the first time it is available to be viewed in its entirety.

A Treasurehouse of Kabbalistic Insights

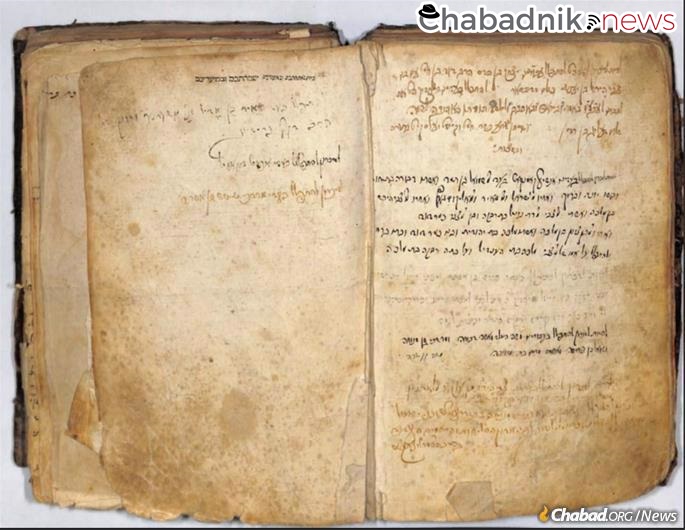

Other rare, handwritten manuscripts that were digitized include the kabbalistic text Ohr Yakar by Rabbi Moshe Cordovero (1482-1570), known by his initials as the “Ramak.” The Ramak was the greatest kabbalist of his day and studied under the famous Rabbi Yosef Caro, who codified Jewish law into the Shulchan Aruch. He studied Kabbalah under his brother-in-law, Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, author of the Lechah Dodi prayer chanted every Friday night. The Ramak authored many deep, mainly kabbalistic works, and his lengthiest is Ohr Yakar, a commentary on the Zohar.

The Chabad Library houses the original manuscript of the Ramak’s commentary on the first section of the Zohar, three volumes of writing that total almost 400 folios.

After the Ramak’s passing, his colleague, Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (1534-1572), headed the circle of kabbalists in the holy city of Safed, Israel. Known by his initials as the “Ari,” or after his passing as the “Arizal,” he taught what became the pre-eminent school of kabbalistic thought. The transcripts of his leading student, Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620) were accepted as the authoritative teachings of the Arizal. These manuscripts were arranged by his son, Rabbi Shmuel Vital in the latter’s handwriting, and became known as Kitvei haArizal, “Writings of the Arizal.” Of the eight manuscripts, six are housed in the Chabad Library.

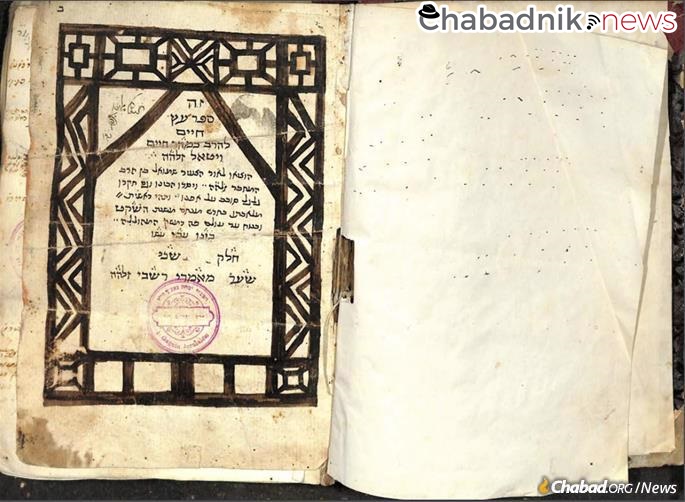

Another manuscript of note is the Mishnah Berurah, the classic 19th-century commentary on everyday parts of Jewish law by Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (1838-1933). His rulings and explanations on Jewish law are widely studied today in many Jewish communities. The Chabad library houses 13 chapters of his handwritten manuscript containing some of the most widely studied sections of the laws of Shabbat.

New Insights into Shulchan Aruch Harav

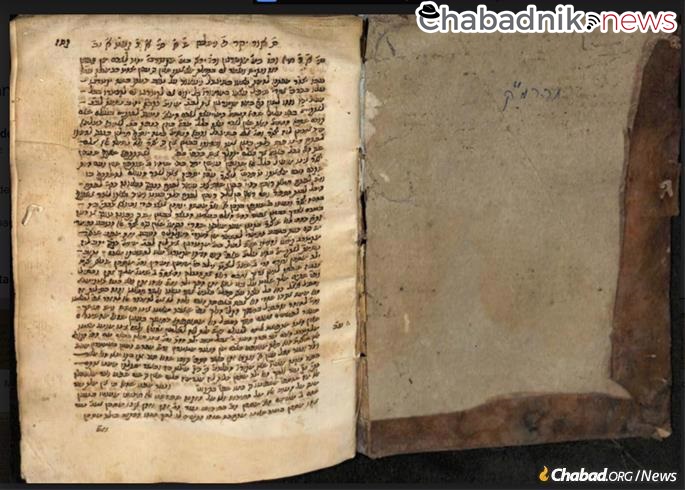

More than a century before the Mishnah Berurah’s publication in 1884, a ground-breaking code of Jewish law was written by the Alter Rebbe—Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1813)—at the behest of his teacher,Rabbi Dovber of Mezritch, the Baal Shem Tov’s successor. It was known as Shulchan Aruch Harav, or the Alter Rebbe‘s Shulchan Aruch. For years, scholars had thought that all of his extant rulings had been published. Large parts of his code were burnt in a fire that ripped through the village of Liadi in the early 1800s, but of the surviving manuscripts, all were thought to have been published in the Zhitomir edition of 1856.

That changed when the digitized archive was released this month. Scholars, researchers, manuscript experts and laypeople spontaneously teamed up on an online forum to discuss, catalog and study these newly released texts.

“Democratization of knowledge is a hallmark of the current era. The library making these manuscripts available to the public is an expression of this, and the crowdsourced discovery and cataloging of information is its actualization,” says Shmuel Super, a Jewish-studies researcher who took part in the grassroots effort to study and catalog the works.

Super himself made a remarkable discovery: an unpublished manuscript of a responsum from the third Rebbe, the Tzemach Tzedek—Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Lubavitch (1789-1866).

For Super, it’s his first deep dive into the world of manuscripts. But others who have joined the crowdsourcing effort have years of expertise with Jewish manuscripts, including some of those who edited and published many of these works.

One such expert is Rabbi Avraham Alashvili of Lod, Israel. “Until this week, we thought we had published all extant parts of the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch,” says Alashvili, who served on the editorial board of the 2001 newly re-typeset and annotated edition of the Shulchan Aruch that replaced the 1904 Vilna edition in use until then. “We didn’t think we’d find more in manuscript form.”

But browsing through various collections of handwritten manuscripts on vastly different topics, Alashvili stumbled across what appeared to be a manuscript of never-seen paragraphs of the Shulchan Aruch. Careful examination and collaboration with others on the discussion forum revealed that these paragraphs were previously unknown. “We didn’t have this manuscript in the library when we published the new edition of the Shulchan Aruch,” he explains, noting that even if it would have been in the library then, nobody would have thought to look for it among pages of other material. In fact, a copy of this manuscript, part of the Schocken Institute’s collection, was only given to the Chabad Library ten years ago.

The new paragraphs include a directive to “be familiar with the writings of the Prophets and their guidance, and all 24 books (of the Tanach) to fill the heart with fear of Heaven,” as well as an admonition not to hate your fellow, even in your heart.

“These two ideas that were revealed comprise the two most central objectives for Jews in today’s age: Love your fellow Jew and study Torah,” says Alashvili. “I feel the Alter Rebbe is sending regards from Heaven, telling us to strengthen the study of his compendium.”