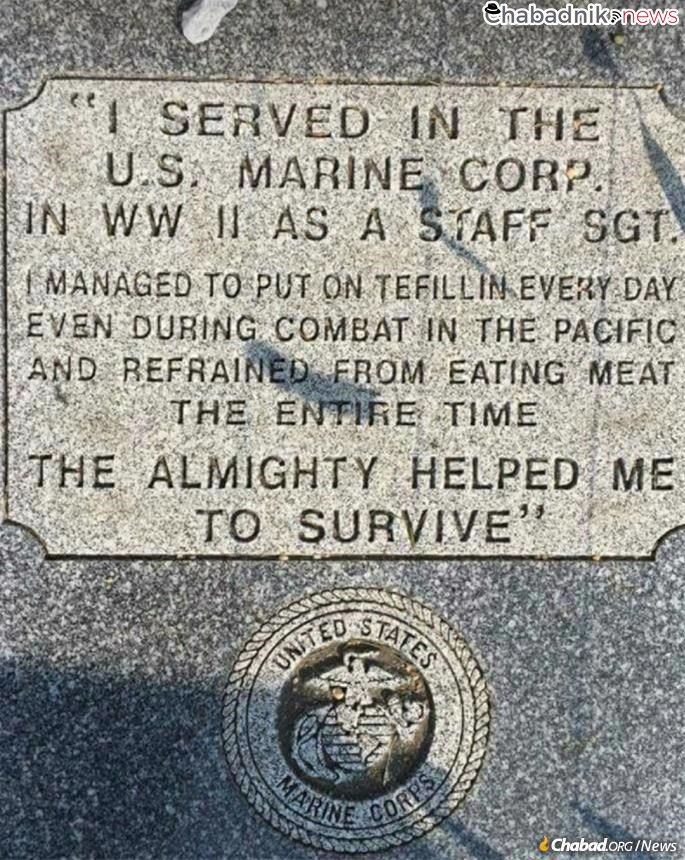

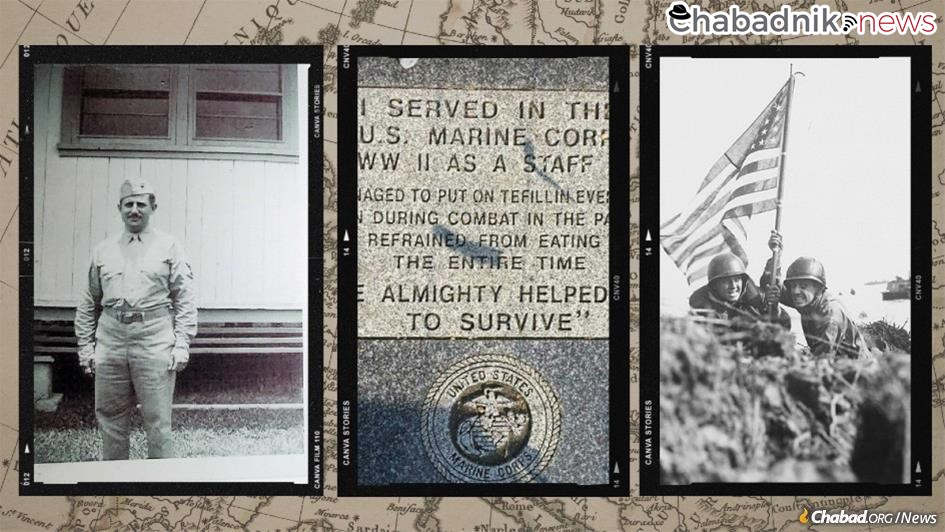

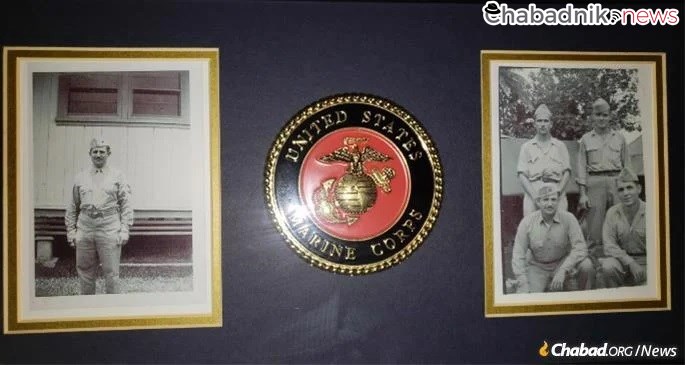

Bernard Haller’s gravestone declares that he never missed a day of tefillin or ate non-kosher meat

When Bernard (Baruch) Haller enlisted in the United States Marines in 1941, he had two goals: to serve his country and to survive. To accomplish these goals, he knew that he’d need the help of a Higher Power. And so Haller, known to friends as Bernie, vowed then and there never to eat non-kosher meat and never to miss a day of tefillin.

So important was this commitment that before Haller passed away on June 29, 2009, he chose the words to be inscribed on his tombstone: “I served in the U.S. Marine Corp. in WWII as a Staff Sgt. I managed to put on tefillin every day even during combat in the Pacific and refrained from eating meat the entire time. The Almighty helped me to survive.”

The epitaph, complete with the Eagle, Globe and Anchor insignia of the U.S. Marine Corps, is one that has gone viral in recent years. Each year, usually around Memorial Day, photos of the moving inscription are tweeted and forwarded on WhatsApp countless times.

“In many ways, I don’t know what my father would think about the attention,” his son Leibe Haller shares with Chabad.org. “He always tried to stay out of the public eye.”

Yet in his father’s story lies a powerful message of Jewish tenacity in the face of all obstacles.

Bernie Haller was born on March 10, 1919, in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, one of second-generation immigrants Wolf and Yetta Haller’s four children.

Wolf, a tailor by profession, bucked the overwhelming tide of American assimilation and fought hard to keep Shabbat.

“The situation was such that if my grandfather had a job on Friday,” Leibe Haller relates, “they’d fire him when they realized he wouldn’t work over Shabbat, and he’d need to find a new job for the next week to come.”

Money was tight for the Hallers, and as a result, young Bernie couldn’t afford yeshivah tuition. Instead, Bernie used to head over to a local yeshivah after school and sit outside the window to catch whatever bits and pieces of the Torah lessons he could.

Courage Under Fire

Despite the struggles, Bernie likewise remained committed to Judaism. When, in 1941, he enlisted in the Armed Forces along with 11 of his cousins, he took the Marine motto, Semper fidelis, Latin for “always faithful,” to heart, both in regards to his country and to his Jewish faith.

Shortly before he was deployed, Haller married his sweetheart, Tziporah Malka Fried. “My mother’s father was a shochet, a ritual slaughterer,” says Leibe. “My father planned on working on the assembly line, removing the feathers from the birds after slaughter. But my grandfather wouldn’t hear of it. He told his son-in-law that he was meant to do greater things.”

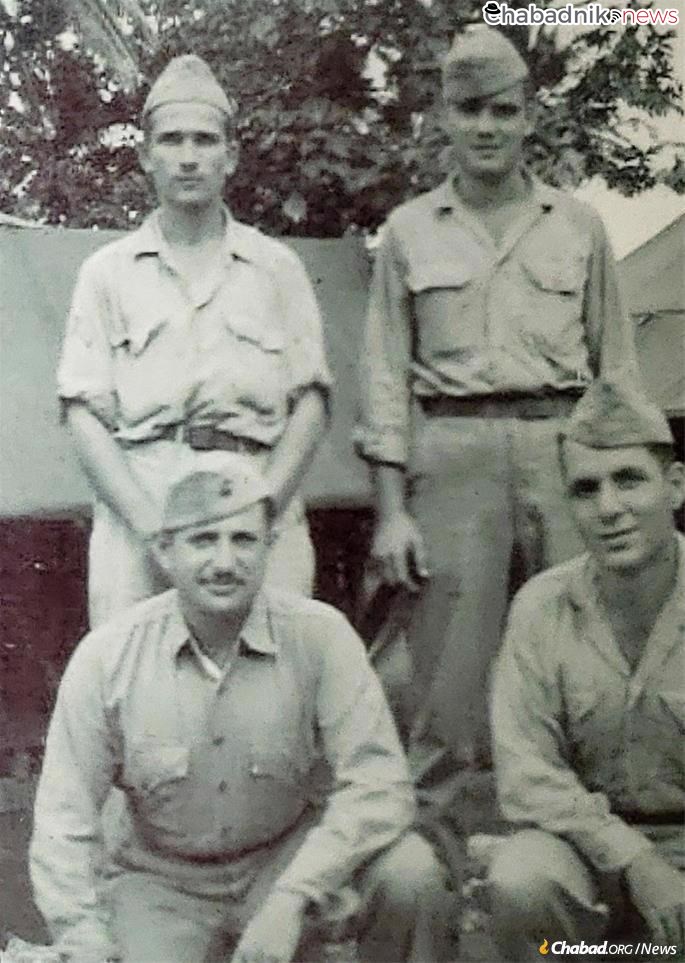

Haller shipped out to the Pacific Theater in 1942, fighting in the Battles of Saipan and Guam. Later, he was stationed in the Philippines.

At one point, taking cover in a foxhole during the heat of battle, Haller counted 10 tracers flashing towards him. Tracers, used to assist in aiming, came on every tenth round of machine-gun fire, which meant that in total, some 100 rounds of fire had passed in the narrow space between his helmet and that of the Marine hunkered next to him.

Haller seldom spoke about his experience during the war, but his son recalls a time when, years later in the Bronx, his father awakened from a traumatic dream in the night and screamed for his rifle. Unspoken was the understanding that this particular nightmare was one of many the elder Haller regularly experienced.

Haller’s religious commitment in the Marines didn’t come easy. When one cook found out that the Jewish staff sergeant was avoiding meat, he began adding lard to the vegetables he served out of spite. When Haller found out, he switched to eating only raw vegetables.

Harassment came in other ways as well. To avoid attracting undue attention from his fellow Marines, Haller would put on tefillin when no one else was around. Still, they taunted him with slurs, referring to him as “Benny the Heeb.” One evening, a group held him down and began to ruffle his hair.

“What are you doing?” Haller asked in confusion.

“We’re looking for your horns,” came the retort. “Jews hide them during the day, but they come out at night.”

But as time went by and they saw Haller’s courage under fire, the harassment faded.

Haller remained ever committed to G‑d, recognizing His works and assistance in the many ways he survived. Like the time his platoon was to be sent to Iwo Jima in the winter of 1945. On the eve of the difficult, bloody battle—nearly 7,000 Americans lost their lives on the island—Haller’s entire platoon developed yellow eyes, a sure sign of yellow fever. Their commanding officer held the platoon back, only for it to later be discovered that the change in eye color was caused by something the platoon had eaten. Because of that, their lives were spared.

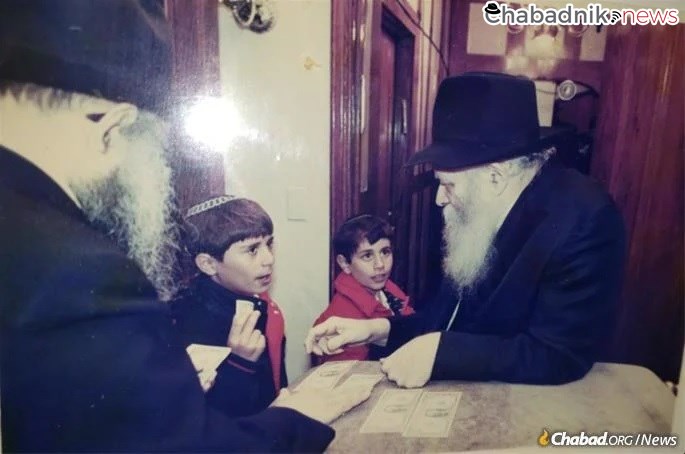

After the war, Haller returned to New York. He and Tziporah Malka settled first in the West Bronx, followed by the Pelham Parkway neighborhood and then Riverdale, all in the Bronx. The couple had three children (Leibe Haller attended Chabad-Lubavitch’s Yeshivas Achei Temimim in the Bronx under the auspices of Rabbi Mordechai Altein) and Bernie worked hard to earn a living, first selling confectionery products and later detergent.

But each morning throughout his long life, he’d rise, put on his tallit and tefillin, and pray to the G‑d of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob—dedicated to the end to his family, his people, his country and to the Almighty, who sustained him through it all.