In honor of 54 years since the reunification of Jerusalem, when the Lubavitcher Rebbe introduced the Tefillin campaign, we are bringing this article out of the archives.

As head of the Mossad, Israel’s national intelligence agency, Yossi Cohen’s routine is anything but humdrum. Beginning his day at the crack of dawn, the recently appointed director is responsible for counterterrorism and the security of the Jewish state. He fields phone calls from parallel agencies around the world, briefs his top operatives, and keeps in close contact with Prime Minister Netanyahu. But before he heads for the office, Cohen takes some quiet time to practice an ancient ritual.

Every morning, the head of Israel’s most important intelligence agency pulls out a satchel containing tefillin (phylacteries), two black boxes with leather straps, and binds them around his head and his arm as he recites a blessing. The small boxes contain scrolls of parchment inscribed with Torah verses, and have been worn by Jewish men in prayer since biblical days. The ritual has a way of centering Cohen, rooting him in his past as he works to stay ahead of Israel’s enemies in a fast moving world of intrigue and espionage.

Chasidic philosophy teaches that tefillin serve as a conduit, linking the physical with spiritual in the Divine service of the Jewish male. But, as with many Jewish traditions that fell out of practice over time, so too with tefillin. When the Lubavitcher Rebbe launched a worldwide tefillin awareness campaign in the days leading up to the Six-Day War of June 1967, the black boxes were an obscure ritual item to many among the largely unobservant Israeli public.

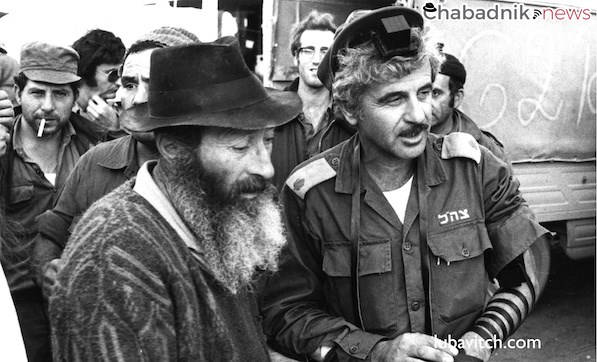

The Rebbe insisted that the mitzvah has deep spiritual potency. “When one puts tefillin on his head,” he said quoting the Talmud, “he projects fear over our enemies wherever they are.” Thus was born a groundbreaking campaign, the first of the Rebbe’s popular mitzvah initiatives, which caught fire in Israel and beyond. Worldwide, Jewish men and boys over the age of 13 responded to the invite to roll up their sleeves and perform the mitzvah for the sake of Israel’s security. The miraculous victory that brought the war to a swift, dramatic end sparked a euphoric feeling of Jewish pride among Israel’s citizens and world Jewry.

In the days following the Six-Day War, Chabad rabbis and volunteers helped thousands bind tefillin at the newly liberated Western Wall. On the streets of midtown Manhattan, in central Paris, London, and a thousand other places, Jews gravitated to the Chabad students and rabbis who were offering them a chance to bind tefillin for Israel’s well-being. With Jerusalem’s reunification, Chabad activists set up a permanent tefillin booth at the Western Wall.

Spiritual Inclusion

Though the daily, weekday wearing of tefillin is among the most fundamental commandments observed by Jewish men, “You shall bind them as a sign upon your head, and they should be a reminder between your eyes” (Deuteronomy), many Israelis may have only performed the practice at their bar mitzvah. According to a Ynet-Gesher poll, some 90 percent of Israeli boys celebrate their bar mitzvah with a traditional ceremony in which the boy reads from the Torah and puts on tefillin. A much smaller segment of the population commits to regular daily tefillin use following the bar mitzvah.

According to an Israeli study from 1965, some 79 percent of Israeli Jewish men owned tefillin, but only about a quarter put them on regularly. About half did not use them at all. Chabad set out to reverse those downward trends, and since the Rebbe’s call to action in 1967, millions of Jews around the world have wrapped tefillin with Chabad.

The offer of sharing the mitzvah with any Jewish male represented a radical shift in philosophy. “The tefillin campaign was revolutionary in the sense that prior to the initiative an Israeli was either religious or not religious,” explains Rabbi Menachem Brod, spokesman of Chabad in Israel. “Chabad came in with a new message that no matter your level of religiosity, you can and should participate in a mitzvah, even just the one time.”

The message was at first greeted with open criticism from certain quarters. Orthodox detractors bristled at the idea of inviting a non-observant Jew to wrap tefillin, and in secular Israeli strongholds such as Tel Aviv, the young Chabad men offering tefillin were seen as a threat to their secular lifestyle. But today, certain orthodox groups are imitating Chabad’s model with their own tefillin stands. And secular Israelis have come to see Chabad’s outreach as an expression of inclusiveness and Jewish unity. The Israeli public, says Brod, has largely warmed to Chabad’s innovative thinking. “Presenting religious experience as a ‘continuum’ was a message of spiritual inclusion that softened the stark divide between the religious and the non-religious in Israel.

Nitzan Dery, a 47-year-old father of three, says that though he is “not exactly religious,” an encounter with a Chabad student who invited him to put on tefillin moved him to connect with his heritage. “I hadn’t put on tefillin since my bar mitzvah,” admits Dery. “Every Friday, I used to pass the Chabad stand and turn down their requests to wrap tefillin, until one day for whatever reason I said yes.”

The simple act struck a chord with him, and he began seeking out the Chabad boys so that he could perform the mitzvah. “Eventually, I realized that though I may not keep other things, tefillin was something I wanted in my life—a point of Jewish connection that I can commit to daily.” The Nahariya native dusted off an old pair that was handed down to him from his father, and has donned them every weekday since.

Go to Where the People Are

The ability to meet each Jew on his own level, wherever he is, may help explain the success of Chabad’s tefillin campaign. Since its inception, the campaign sought to make tefillin easy and accessible to any Jew. Mitzvah mobiles are a standard street fixture and pop-up tefillin booths have become part of the landscape. In Israel, every Friday, waves of volunteers—from students to seniors—encourage men to put on tefillin prior to the start of Shabbat. Many Chabad men carry a pair of tefillin with them “just in case.”

In a nod to the country’s “Start-up Nation” mentality—Israel is one of the world’s most vibrant technology communities outside Silicon Valley—Chabad even developed a tefillin app that reached position #27 in the Israeli app store.

The ubiquitous campaign brought Jewish pride and precepts into public consciousness. The idea, to have “your Jewish blood pressure taken”—a play on the tefillin bindings of the arm—resonated beyond traditional Jewish circles. Today, Israelis can expect to be stopped at a bus station in Tel Aviv, on a college campus in Haifa, or even in their own office, with the offer to wrap tefillin.

Rabbi Mordechai Siev, a Chabad rabbi and American transplant, first started manning a tefillin stand when he arrived in Israel in the mid-80s. The language barrier was a non-issue, as no words needed to be exchanged.

“Often when people see a tefillin stand in Israel, they’ll just come over. They don’t even say anything and just start wrapping,” the rabbi says, estimating that a little less than half of Israelis are able to complete the ritual on their own. “Others know how to do it but if Chabad wasn’t there they may not bother.” One volunteer explains that often when he asks passersby if they put on tefillin they will reply in the affirmative. Yet when he asks if they had put on tefillin that day, many reply “I haven’t had a chance” or “I forgot.” The convenience and accessibility of the Chabad tefillin stands ensure that they can perform the mitzvah on the spot.

Arms for Israel

In late February, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Dan Shapiro ran in the Tel Aviv marathon. During the race, he stopped to don tefillin with the help of Chabad representatives who were present along the route. Upon completing the race, the ambassador proudly broadcast his mitzvah to his Facebook and Twitter followers.

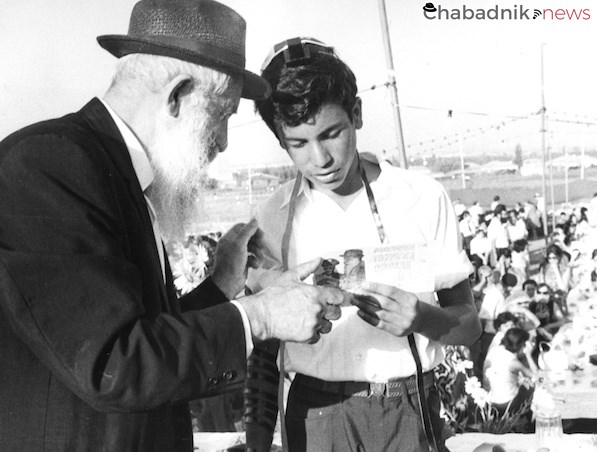

Politician photo-ops with tefillin have become a bit of an Israeli tradition. In an encounter widely publicized in Israeli media, Israel’s late prime minister Ariel Sharon, accompanied by other high-ranking IDF officials, visited the Western Wall soon after the 1967 war and agreed to wrap tefillin with a Chabad rabbi. Sharon told reporters that it was the first time he had put on tefillin since his bar mitzvah. Before long, it was all over the news. Inspired by his act, many Israelis followed suit—some for the first time in their lives.

The Israeli army in particular has become a tefillin touchpoint. Military service in Israel is mandatory, and the IDF is thus fairly representative of Israel’s diverse population. Chabad’s presence at army bases and its volunteer activities with IDF soldiers has given Jews of all stripes a tefillin experience. “Chabad’s tefillin efforts are intrinsically connected to the Israeli army, as the danger facing its soldiers was the impetus for its founding,” Brod explains. “We make a special emphasis to reach out to and engage IDF soldiers.”

And their children. Ever since the Six-Day War, Chabad has hosted an annual bar mitzvah ceremony for the children of Israel’s fallen soldiers. At each emotional celebration, the children are presented with a gift by Israel’s leaders: a set of their own tefillin. This past April, 110 orphan Israeli children celebrated their bar and bat mitzvahs with Chabad in Jerusalem.

Tying the Physical and the Spiritual

With thousands of visitors passing through daily, Chabad’s permanent stand at the Western Wall (the Kotel) has become a landmark at Judaism’s holiest site. Chabad representative at the Kotel, Rabbi Shmuel Weiss, says the stand serves on average, 500 men a day in the winter, and over 1,000 men a day during peak summer travel season. On Jerusalem Day, when around 20,000 youth visited the Kotel, the number topped off at around 1,500.

The stand opens at at sunrise and runs non-stop until sunset, the last minute that it is permissible by Jewish law to put on tefillin. Weiss says many have come to rely on Chabad’s services. “Some say ‘I won’t put on tefillin this morning since I am going to the Kotel and I’ll put it on with Chabad there’.” Conversely, others who do not normally do the mitzvah see it as an opportunity: “I am at the Kotel, how can I not put on tefillin?”

In a personal narrative describing how he wrapped tefillin with Chabad at the Kotel, journalist Liel Leibovitz wrote in a recent article that the meaningful encounter led him to daily tefillin observance. Despite not “fully understanding” why he does this, “no matter how I choose to manifest my relationship with the Creator, I start each day by acknowledging that this relationship exists, that it matters, and that everything that follows in the day should be, in part, a reflection on how my thoughts and my actions conform to or challenge my faith.”

Weiss expounds on the phenomenon. “In the Land of Israel, we believe that everything physical has a spiritual element.” It is when the straps and boxes of coarse cowhide containing the loftiest of Jewish prayers are placed on the head and on the arm, that they both meet.

Tefillin Anyone?

The Tefillin campaign established by the Lubavitcher Rebbe in 1967 to raise awareness of this cardinal mitzvah, has since been promoted by Chabad emissaries and adherents all around the globe. As Israel is home to the world’s largest Jewish population, Chabad has focused intense efforts on tefillin in the Holy Land.

Now approaching the 50th anniversary of the campaign, Chabad will ramp up its tefillin activities. Rabbi Meir Leider, who is part of a committee dedicated to improving and enhancing the nation-wide tefillin effort, says that today Chabad in Israel shares tefillin with about 13,000 Jewish men a week. Yeshiva students, rabbinical students and Chabad lay people dedicate time every week to participate in the campaign.

With a target goal of raising Chabad’s “wraps a week” to 20,000, Leider and others have created new materials to step up the outreach. New, premium and weather proof tefillin bags have been created to allow ease of use, and clever pop-up tables and awnings that weigh under five lbs make setting up a tefillin booth anywhere quick and easy. The changes translate to numbers: in the time it once took a volunteer to wrap tefillin with 20 men, he is now counting 40.

Chabad is also adding more permanent tefillin stations. Today, five are scattered throughout the country, including the stand at the Kotel and a kiosk at Ben Gurion airport. Five new locations are in the works, bringing the country wide total of permanent tefillin spots to ten. Some of these have set the bar high, aiming for 30,000 wraps a month.

Source: https://www.lubavitch.com/tefillin-the-pulse-of-israel/