It was unseasonably cold on the first night of Passover back in 1979. Snow had fallen the day before and melted into slush puddles that made walking unpleasant. The evening prayers had ended, and everyone was hurrying home to finally begin the Seder.

Not the Rebbe. Before returning to his home to make the Seder with his wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Moussia, the Rebbe took an hour-long detour, visiting several large Seders in Chabad yeshivah dormitories. Among them was one for young women celebrating what may have been their first Seder ever, and another for children and teenagers from Iran: several weeks earlier, after the Islamic Revolution, more than a thousand Jewish girls and boys had been airlifted out of the country at the Rebbe’s behest—a stunning rescue operation conducted by the late Rabbi Jacob J. Hecht—and settled into homes in the community.

I was part of a small entourage that accompanied the Rebbe on those Seder-night rounds. I observed the Rebbe as he walked through the snowy streets, cold slush penetrating his shoes. The joy he took in visiting the students at their Seder tables, it seemed, eclipsed any discomfort he may have felt. To the Rebbe, Zman Cheirutenu, the Festival of Our Freedom, was a time flush with the power to make us—individuals and the Jewish collective—soar to a higher realm.

As far as the Rebbe was concerned, the matzah, maror, and four cups of wine were more than symbols of an ancient story. They were the very means by which we connect—to G-d, but also to each other. Earlier that day, the Rebbe had asked Rabbi Hecht, who had organized the Seder for the young Iranian escapees, for some of the maror that they would be eating. He wanted to partake of their bitter herbs, to feel their suffering.

***

Each year, during the weeks leading up to the Passover holiday, the Rebbe wrote a public letter, addressed “To the Sons and Daughters of Our People Israel, Everywhere.” In these letters, the Rebbe wrote often, with great pathos, about the “fifth child,” the one who does not show up to the Seder table. Who would look out for those children, adrift in a world far from the family?

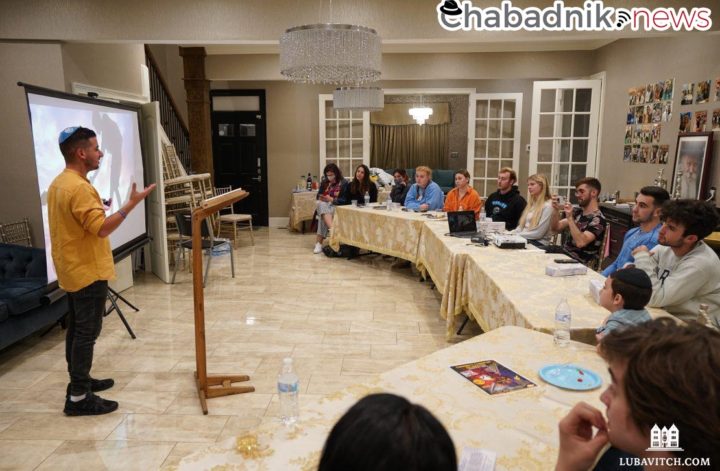

Even before the advent of Chabad Houses, the Rebbe’s efforts to find these “sons and daughters” who had fallen off the radar are the stuff of legends. In the 1970s, Chabad Houses began sprouting up; the table extensions came out and the guests came in.

Around the same time, young Jews in search of meaning began making their way to Chabad’s adult men’s and women’s yeshivahs, among them young Jews who returned disenchanted from ashrams in India, spent by the countercultural movement, and Russian Jews who made it out of the Soviet Union for their first taste of freedom.

That night in 1979 was truly different from all others. The Rebbe visited the boys’ yeshivah, the women’s yeshivah, the Seder for Russian Jews, and the Seders of the recently arrived Iranians. At each place, he patiently took the time to note details, to see that everyone had what they needed. At each, he spoke to the students for a few minutes, and blessed them.

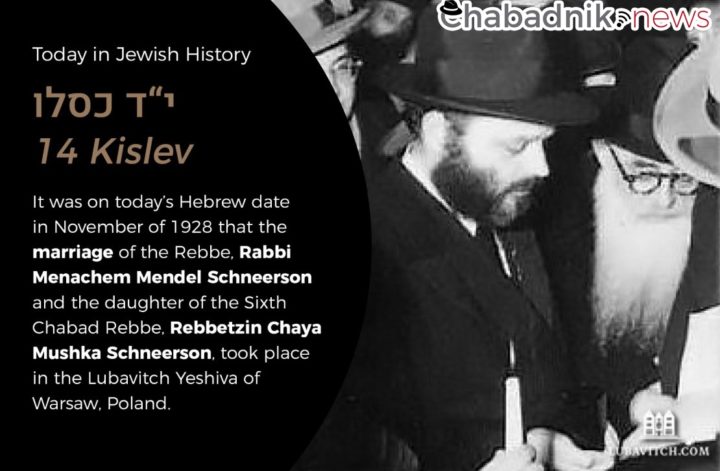

The Rebbe and Rebbetzin did not have children of their own. As I observed the Rebbe on that Seder night, I saw the love of a parent who longs for his children, and I understood. These were the Rebbe’s sons and daughters, and he, like a father, beamed with joy to finally see them at his Seder table.

Source: https://www.lubavitch.com/sons-and-daughters-at-the-seder-table/