Spread wry Chassidic wit and wisdom throughout the Holy Land

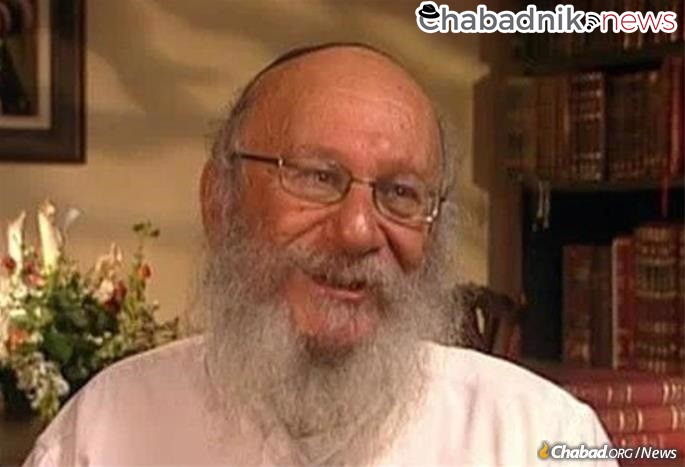

Rabbi Zushe Posner, the beloved American-born mentor to generations of Israeli yeshivah students whose piercing Chassidic wit and devotion to straightforward honesty was a canon of its own, passed away on Friday, 12 Shevat. He was 85 years old.

His decades-long career in Jewish education defies the traditional contours of an obituary, as his legacy lies not in the institutions he built but in the ideals he propagated, and the large and small ways he influenced his students, as well as virtually everyone else with whom he came in contact. He was slight in stature with an evident physical disability, which only added to his reputation as a larger-than-life role model and giant of spirit.

Zushe Posner was born in 1936 in Elizabeth, N.J., where his parents, Rabbi Sholom and Chaya Posner, ran a kosher butcher shop. It was a complicated delivery that left him with limited dexterity on one side throughout his life, and letters sent by the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—from Riga, Latvia, were filled with wishes for a speedy recovery for baby and mother, one sent shortly after the birth and one several months later.

When Zushe was a toddler, the family relocated to Chicago, where his father took a position as shamash (“caretaker”) of Congregation Bnei Ruven and served as the Sixth Rebbe’s unofficial liaison to the city, which then boasted a Chabad Chassidic community numbering in the thousands.

Like his older brothers Zalman and Leibel, when Zushe was still middle-school age, his parents sent him to study at the Chabad-Lubavitch yeshivah in Brooklyn, N.Y., which the Sixth Rebbe had re-established in 1940 after arriving from Nazi-occupied Europe.

On the morning of 10 Shevat—the Shabbat day in 1950 when the Sixth Rebbe passed away—young Zushe was the one to walk from Crown Heights to Brownsville to share the bitter news with the community of Chabad Chassidim there.

A Devoted Chasid’s Lifelong Work

Exactly one year later, Zushe was on hand when the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—formally accepted the mantle of leadership.

In 1956, a terrorist opened fire on students at a trade school in Kfar Chabad, Israel, killing six, including a teacher. In response, the Rebbe encouraged the Chassidim to expand their activities in Israel and redouble their efforts around the world.

The people of Israel were reeling—not just from this and other deadly terrorist attacks, but from the crushing poverty and fears of invasion and war with surrounding Arab nations that permeated the fledgling state. The summer following the attack in Kfar Chabad the Rebbe sent a delegation of 12 yeshivah students to the Holy Land as his personal representatives to bring inspiration and hope to their brethren.

The final student to be added to the list was Posner, who was then learning in the Chabad yeshivah in Montreal. The Rebbe stipulated that he could participate only if he was found to be in sufficiently good health. Dr. Avrohom Seligson gave him a clean bill of health, provided that he eat butter “to strengthen his bones.”

The Rebbe’s Instruction to Stay in Israel

While in Israel, Posner received a telegram from the Rebbe instructing him to remain there even after the others returned home. It was then that he began a 66-year-long “career” of spreading his unique take on Chassidism and the importance of developing a spiritual connection to the Rebbe wherever he went.

After two years in Israel, he returned to New York in 1958 to attend his sister’s wedding. But he didn’t remain there long, as the Rebbe soon sent him back to Israel and personally participated in the farewell reception arranged in his honor (the Rebbe’s remarks are published in Likkutei Sichot, vol. 2, pp. 632-35).

During the event, the Rebbe spoke highly of Posner’s willingness to travel great distances to work in the field of Torah education. As per the Rebbe’s directive that he teach, he began teaching in the Chabad school in the Zarnuqa refugee camp, where Jewish immigrants who had fled Arab lands were being settled.

The following year, he married Yehudit Kibudi, and the couple settled in Brosh, a tiny settlement in the country’s south, where they both began teaching at the local Chabad school. At the time, Brosh was a very primitive place, and Posner later recalled that they had to eat all their Shabbat leftovers right away since they had no refrigerator, and the food would spoil quickly in the oppressive heat.

In time, they established their home in Lod, in central Israel, where he served in a variety of positions at the local yeshivah, and in later years, other yeshivahs as well.

A Legendary Bond

Posner’s personal bond to the Rebbe was legendary, and he counted the days and the hours that had passed since the Rebbe’s passing in 1994, forever looking forward to Moshiach’s arrival when the departed will rise once again.

He spoke his mind without fear of ruffling feathers. With deadpan humor and self-depreciation, he called out artifice and pretense, demanding authenticity from everyone—from communal leaders and incoming freshmen—with consistency and razor-sharp insight.

To him, complacency and smugness were anathema, to be avoided like the plague.

“Reb Zushe was a man of truth,” recalls Shlomoh Ben-David, a former student of his in Lod and now a businessman in Miami. “The more I mature and gain life experience, the more I value Reb Zushe and his unpretentious ways.”

Ben-David recalls how his teacher once asked the class who wanted Moshiach to come. As to be expected, hands shot up. “Really, you want Moshiach. Why do you want Moshiach?” he asked, and then went on to paint a picture of how much their lives would change with the rebuilding of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and the re-introduction of animal sacrifices and purity laws.

“Rather,” he concluded to the class, “there is a Rebbe in New York who desperately wants Moshiach. I love the Rebbe, and so I want what he wants. No more and no less.”

Posner had an aversion for platitudes. To him words like “unity” and “dedication” were no more than distractions and diversions, to be avoided at all cost.

In his personal and professional life, he developed friendships and relationships in the most unexpected places. “He was like a father, like a brother,” says Juma Azbarga, a Muslim Bedouin who knew him through his work at the education ministry. “Whatever he said was sacred. A day without Zushe was empty. Whatever I say cannot reflect who he was as a human, as a rabbi.”

His home was always open to seekers of all ages, and students knew they were welcome to come and talk with him at all hours, even waking him in the middle of the night. Friday evenings at his home were legendary, as extra benches would be set up around his modest dining-room table, pitchers of punch were poured, and he would regale students with memories, Torah teachings, tunes and his near-constant call for genuineness and devotion to Chassidic ideals.

Beyond the walls of the yeshivah, he frequently spoke for crowds at Chabad centers, synagogues and communal gatherings.

Unvarnished Love in Many Languages

With his command of English, Yiddish and Hebrew, he connected to audiences of all ages and backgrounds, berating, provoking, asking inconvenient questions and demanding authenticity, growth and change—all with a dollop of unvarnished love.

“I remember when 770 was just purchased,” he said to a large crowd a little more than a month before his passing. “And you’re going to start telling me what is 770?”

He was wheezing and needed to sit down in the middle of his address, but words were as fiery as ever. “I am sick,” he said from his seat, “but if this is the last time here, I won’t cry. Why would I cry? For the 27 years and six months that we have not been together with the Rebbe.”

As an 18-year-old, he once wrote a note to the Rebbe detailing the various communal positions he did not want to take. In response to the Rebbe’s question of which career he did want, he replied: “a chicken farmer.”

Indeed, over the years, he raised thousands of Chassidic hatchlings, nurturing them into inspired, dedicated and learned leaders, whom he would lovingly refer to as his “children.”

Predeceased by his wife in 2019, he passed away surrounded by family members 71 years and one day after he heard the landmark Chassidic discourse Basi Legani from the Rebbe on the night he officially accepted the role.

He is survived by his children: Lizik Naparstak (Kfar Chabad, Israel); Rabbi Yossi Posner (Birmingham, Ala.); Rabbi Mendy Posner (Plantation, Fla.); Chana Liberow (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Liora Popper (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Rabbi Shmuel Posner (Davie, Fla.); in addition to many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He is also survived by his siblings: Rabbi Leibel Posner (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Bassie Garelik (Milan, Italy); and Sara Rivka Sasonkin (Taanach, Israel).