Those who knew him all use the same Yiddish words to describe Rabbi Yosef Neumann, who was brutally stabbed at a Chanukah celebration in Monsey, N.Y., and passed away on Sunday of his wounds: “He is a fartzeitishe Chassidisher Yid,” a Chassidic Jew from a bygone era, an unending font of Chassidic stories, anecdotes and adages. Although he suffered from health conditions in recent months and used a walker, when the attacker entered the Chanukah celebration, he tried to fight him back with his cane and even attempted to throw a table at him. Three months after the attack, Neumann died of his wounds today. He was 72 years old.

To many regular worshippers at the synagogue he frequented, the spiritual center of the Kosson Chassidic group to which his family had belonged for generations, he was known as a persistent collector of tzedakah for the poor. With a bag in hand, he would ask everyone who entered the synagogue for a donation in Hungarian-accented English or Yiddish.

To the close-knit group of young Chassidim who gravitated around him for decades, he is an impressive scholar, well-versed in all areas of Jewish teaching, from Talmud to Kabbalah.

And to the poor families in Israel who benefited from his funds, he was an agent of mercy.

“He never kept a penny for himself,” revealed Yosef Eliyahu Gluck, a close friend and hero of the horrific stabbing episode who successfully chased away the attacker with a table. “He used to go through a lot of effort to take care of ‘his families,’ people everyone else overlooked. He used to exchange the money he collected for crisp $100 bills to make sure the families would have no problem using the money as soon as they got it.”

The attack took place after Rabbi Chaim L. Rottenberg, the Rebbe of Kosson, had kindled the menorah on the seventh night of the holiday in the presence of family and community members. As those gathered began to leave and make their way to the synagogue next door, witnesses say the attacker calmly walked in, drew his weapon and said: “No one is going anywhere.”

He then began swinging his machete wildly at people in the room, injuring five. In a press conference today, the family detailed the numerous serious wounds that Neumann suffered in the attack. He sustained multiple injuries, including a fractured skull, a sliced neck and a fractured arm.

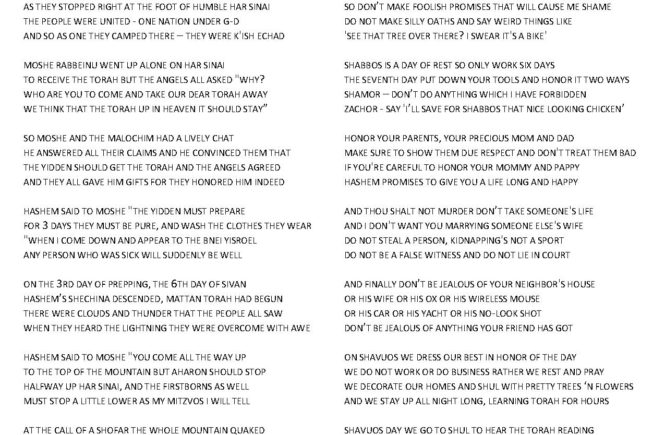

Rabbi Yosef Neumann surrounded by his beloved community.

Devoted to Torah From Hungary to America

Neumann was born in 1947 in post-Holocaust Szerencs, a town in northern Hungary with a rich Jewish history. His father, Rabbi Mechele Neumann, was a devoted Chassid and a well-regarded Torah scholar. As the new Communist regime tightened its grip on the tattered remains of Hungarian Jewry, it became clear to the Neumanns that their future lay elsewhere. But it was too late. The borders to the West had been sealed shut.

Their chance came in 1956 during the short-lived Hungarian revolution. In the chaos of the uprising, many Jewish families, including the Neumanns, managed to escape into Austria. Nine years old at the time, Yosef was carried over the border in a bag with his mouth stuffed to prevent him from calling out in fright.

The family remained for a while in Vienna, where Rabbi Mechele served as rabbi. Yet even while there, his focus was global. One of the fundamentals of Judaism is the observance of family purity (niddah). Recognizing that this mitzvah was becoming neglected, the rabbi had literature printed in dozens of languages, which he then distributed to communities around the world.

This labor of love would eventually be passed on to his son, Yosef, who worked closely with Chabad rabbis around the world to distribute his booklets. Yosef met privately with the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—three times in the 1960s, and frequently visited the Rebbe’s synagogue to attend farbrengens and study Chabad teachings.

A natural scholar who was rarely seen unaccompanied by a Torah book, Yosef engaged in several professions. He ran a grocery store in Brooklyn, drove a milk delivery truck and then opened a fish market. But his main occupation was always the joyous study of Torah.

In his final years, he lived in the lower level of the complex where he was attacked, and which housed both the residence of the Rebbe of Kosson and his synagogue.

“I would often visit him on Shabbos,” says Gluck. “He would enjoy his meal with a stack of six or seven seforim (holy books). That was his pleasure.”

“He’s like everyone’s uncle,” adds Gluck’s brother-in-law, Yisroel Kraus, who studied with him on a regular basis. “We young students used to like to talk with him and learn with him. He knew about everything and taught us little-known aspects of Torah, which are not widely taught in yeshivah.”

For every occasion and for every Torah topic, he seemed to have a gematria, a hidden connection couched in the numerical value of the Hebrew letters.

“To us, he has always been someone special,” says Kraus. “He lived and breathed Chassidus, a glimpse into a past generation.”

He died more than three months after the stabbing, leaving a gaping hole in the hearts of those who knew him.

Rabbi Yosef Neumann is survived by his children, David Neumann, Sruly Neumann, Moshe Neumann, Gitty Jacobowitz, Chaya Yitty Bodansky, Lea Klein, and Nicky Kohen, and grandchildren.