Rabbi Yehudah Leib Groner spent decades serving as an aide to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. Over that span of time, Rabbi Groner was a firsthand witness to many of the events that sent ripples of transformation from the Rebbe’s office in New York in ever expanding circles across the globe. He passed away on April 7, the eve of Passover, after several very difficult weeks battling the coronavirus. He was 88 years old.

Yehuda Leib Groner was born in New York in 1931 to his parents, Mordechai Avraham Yeshaya and Menuchah Rochel, who was a descendant of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad and the author of the Tanya. His parents fiercely guarded the Torah way of life at a time when it was not at all easy to do so. As a teenager he enrolled as a student in the Central Lubavitch Yeshivah, Tomchei Tmimim, reestablished on American shores in the new headquarters of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory (1880-1950) at 770 Eastern Parkway.

Though he probably didn’t know it at the time, young “Leibel” was destined to spend the rest of his life working at 770. Like many of his peers, he gravitated naturally to the Rebbe’s son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, and would ask him questions he had in learning, both relating to normative Talmudic topics and to more esoteric issues that are found in Chassidic teachings and Kabbalah. Leibel was a serious student, and grew into a scholar who was knowledgeable in both areas.

At that time, back in the late 1940s, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson was catalyzing new approaches to Jewish education, and sent young students like Groner far and near to ignite the spark of Torah and mitzvot wherever Jews had scattered. At the same time, Rabbi Schneerson (who would soon succeed his father-in-law as Rebbe) was also pioneering a revolution in Chassidic scholarship and publishing, preparing key texts from the successive Chabad rebbes for print that had previously remained in manuscript, or were circulated in mimeographed copies. Energetic activism and publications for Jewish children went hand in hand with the painstaking intellectual work of transcription, annotation, and indexing of complex and innovative works of Halachic adjudication and Chassidic illumination.

The yeshivah hall where Leibel and his peers studied was just down the hall from Rabbi Schneerson’s office, and they were captivated by his dynamic blend of pricipaled practicality and profound learning, as well as by his deep aura of dedication and urgency. Circa 1949, while still a student, Groner set himself to help out wherever he could, taking on the sort of laborious and indispensable tasks that transform a raw text into a polished publication. In many ways this set the tone for much of what was to come: A willingness and desire to be of service, to help, to facilitate, to ease the burden of leadership.

Along with his youthful peers he was party to the dramatic events of 1950, following the passing of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. All hope for the future of Chabad, and for a revitalization of Jewish life in the aftermath of the Holocuast, rested on the challenge of prevailing on the Rebbe to fully accept his position as his father-in-law’s successor. This was finally achieved one year later, in 1951, when the Rebbe delivered his first formal chassidic discourse and landmark “mission statement.” From then on Groner’s vocation in life was to serve the Rebbe, to facilitate his work, and to observe his holy conduct.

After his marriage to Yehudis Gurevitch in 1954, he joined the group of the Rebbe’s secretaries serving under the Rebbe’s chief of staff, Rabbi Chaim Aizik Hodakov. Wherever his help was needed he proved himself an able and willing aid. He served together with other members of the secretariat as a timekeeper and doorkeeper for long nights when the Rebbe received people for private audiences. The secretaries would also take dictation from the Rebbe and ensure the efficient dispatch of his responses to the voluminous correspondence directed to him from around the world. Ranging from responses to individuals and families to community leaders and heads of state, these interactions were always loaded with deep personal meaning and often with geopolitical significance too.

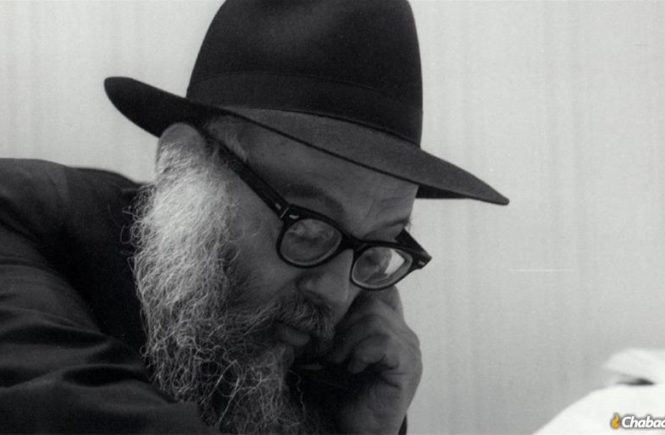

Rabbi Groner served at the Rebbe’s side for more than 40 years.

At the same time Rabbi Groner continued to assist with the scholarly work of publishing. Among other works he was involved in, he was instrumental in compiling and publishing Sefer Haminhagim Chabad, based on the Rebbe’s glosses and instructions, which became one of the most authoritative sources for customs particular to Chabad Chassidim. Back in his youth he and his yeshivah peers had grown accustomed to asking the Rebbe questions that arose in the course of their studies. In the years to come, he would remain an engaged student, listening carefully to the Rebbe’s many talks and discourses and sometimes following up with questions.

For many years Rabbi Groner was also a teacher at the Beth Rivkah school for girls. But in 1977, the Rebbe suffered a heart attack. Rabbi Groner now committed himself to working full time as an aid to the Rebbe, sensing that the need for additional support would now be greater.

In the later years in particular, Rabbi Groner was there wherever and whenever the Rebbe appeared, ready to be of service, a gesture he took on as a sign of respectful attentiveness befitting the stature of so great a leader of the Jewish people. Following just a few paces behind, he would be there whenever the Rebbe entered the main synagogue at 770, whether to participate in communal prayer, lead a farbrengen, or to share words of inspiration with a gathering of young children. He would likewise be there to aid the Rebbe as he spent many hours distributing dollars to the thousands who stood in line each Sunday.

As one of those rare few with such close proximity and regular access to the Rebbe, it was natural that he became both a conduit and a gatekeeper. People turned to him with all kinds of requests to seek the Rebbe’s advice and blessing on their behalf, while he sought simultaneously to protect the Rebbe’s space, time, and privacy. As the number of people who sought the Rebbe’s guidance grew exponentially, the Rebbe relied less on a more formal format of correspondence and would inscribe his responses in brief note form directly on the original letter that he had received. The responses were then relayed telephonically (and later by fax) to the correspondent. The number of letters and notes that passed in this manner through Rabbi Groner’s hands is unquantifiable.

In recent years Rabbi Groner spent time traveling to visit many communities where the Rebbe’s emissaries serve, inspiring audiences with memories of the many special things he merited to see.

He is survived by his wife Yehudis (nee Gurevitch), who he married in 1954; by his sons, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Groner (Charlotte, NC), Rabbi Menachem Mendel Gorner (Kiryat Gat, Israel), and Aharon Groner (Monsey, NY); by his daughters, Gitty Levin (Ft. Lauderdale, FL), Chaya Sandhaus (Crown Heights, Brooklyn, NY), Sarah Tennenbaum (Crown Heights, Brooklyn, NY), and Shaina Wilhelm (Crown Heights, Brooklyn, NY); and by many grandchildren and great grandchildren.

L.to R.: Rabbi Groner, Rabbi Dovid Raskin, Rabbi Abraham Shemtov, and Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky.