A servant of G-d on a lifelong search for truth

It was late one Purim afternoon when Rabbi Mendel Aronow made his appearance at a farbrengen gathering in Toronto’s Chabad-Lubavitch yeshivah. Joining the students’ Purim festivities—the yeshivah was located just across the street from his home—he told them that later in the evening, he would reveal a deep secret that had been taught in the original Tomchei Temimim yeshivah in the White Russian village of Lubavitch.

As the hours wore on, Aronow remained silent, choosing instead to listen to the words of inspiration being shared by others. Late at night, when all but a few brave souls had retired to bed, he finally spoke up.

“In Lubavitch, hot men oisgelernt, az men lernt nisht, vaist men nisht,” he finally shared. “In Lubavitch, it was taught: If you don’t study, you won’t know.”

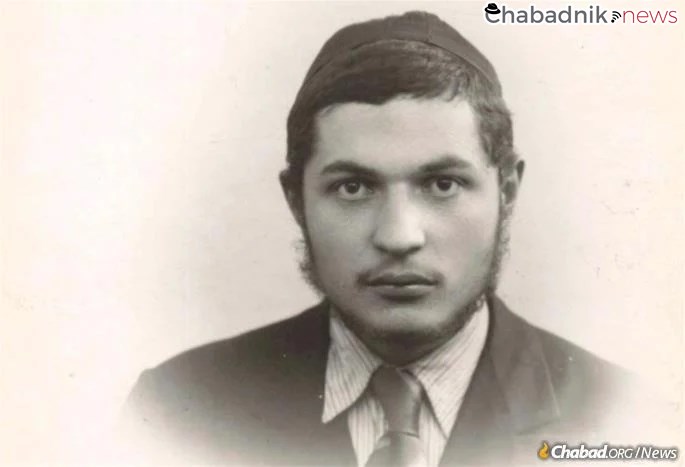

To the countless individuals who interacted with the Russian-born Aronow, who passed away on June 15 (5 Tammuz) at the age of 93, the substance and style of this story encapsulated his unique personality, earnestness and lifelong quest for truth. There were no frills, no externalities: If one wished to be learned, he had to study. If one wished to truly serve G‑d, it would take hard work and effort.

It was this same genuine sincerity that endeared him to a diverse range of members of Toronto’s broader Jewish community over the seven decades that he called the city home. Relatives, students and acquaintances all expressed similar sentiments when describing him.

Aronow was a man whose quest for emes (“truth”) shone through brightly, illuminating even his mundane actions and inspiring all those around him.

Underground Childhood

Menachem Mendel Aronow was born to Rabbi Zelik and Chava Aronow on Jan. 28, 1928 (6 Shevat, 5688), in Orsha, a mere 35 vyorst (kilometers) from the village of Lubavitch three hours east of Minsk in Soviet Belarus. The family carried an illustrious lineage in more than one way: As Kohanim, their last name paid tribute to Aaron the High Priest. At the same time, the Aronow family traced itself back directly to the original followers of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

Aronow would be forever proud of his pedigree, and atfarbrengens point out, in his inimitable way, that in his veins flowed “six generations of Chabadsker blood.”

To him, though, this was not merely a distinction to be proud of but a responsibility to carry. Indeed, sacrifice and dedication for Torah and mitzvot were imbued from the cradle.

Aronow’s father, Rabbi Zelik Aronow had studied in the Tomchei Tmimim Yeshivah in Lubavitch, where he obtained a name for himself as a Torah scholar and a truly G‑d-fearing individual. He received rabbinic ordination from the renowned Rabbi Dovid Tzvi Chein, a Chabad Chassid and rabbinical figure widely known for his tremendous Torah knowledge and piety.

At the time of Mendel’s birth, his father’s main occupation was an illegal one: teaching Torah to groups of children, deemed criminal by Soviet law. Eventually, the law caught up with him; in 1932, he was arrested in a late-night sweep of rabbis and Jewish religious functionaries in Orsha.

Young Mendel, just 4 at the time, recalled decades later that he had slept through the secret police’s raid of their home. In the morning, he awoke to find his mother shell-shocked in an overturned house. She remained standing in a trance until his aunt arrived and helped her begin putting the house back in order.

The day was not yet over when Chava began focusing her efforts on having her husband released. When her husband was subsequently sentenced to eight years of hard labor in Siberia, Chava went knocking on all government doors and departments to help secure the release of her husband, but to no avail. Chava did not despair, and after three and a half years, Mikhail Kalinin, head of state of the USSR, responded to a letter she had written asking for a pardon. Kalinin, known to play the act of a merciful head of state, responded to her request by cutting her husband’s sentence in half.

When Zelik Aronow finally did return from the Gulags, he was a shadow of his former self. With the head of the household a marked criminal, the Aronow family was then forced to move to Yegoryevsk, a small town not far from Moscow.

Following the Nazi invasion of the USSR during World War II, the family escaped to Samarkand, Soviet Uzbekistan. Having never recovered from his stint in Siberia, Zelik Aronow took sick shortly after their arrival in Samarkand. He passed away in the summer of 1942, leaving a widow and two orphans. Mendel was 14 years old at the time.

As the war continued to rage, the Soviet authorities chose to overlook the growing Jewish communities in faraway Uzbekistan. Seizing the opportunity, Chabad Chassidim set up clandestine yeshivahs in Samarkand and Tashkent, and Mendel joined one such school.

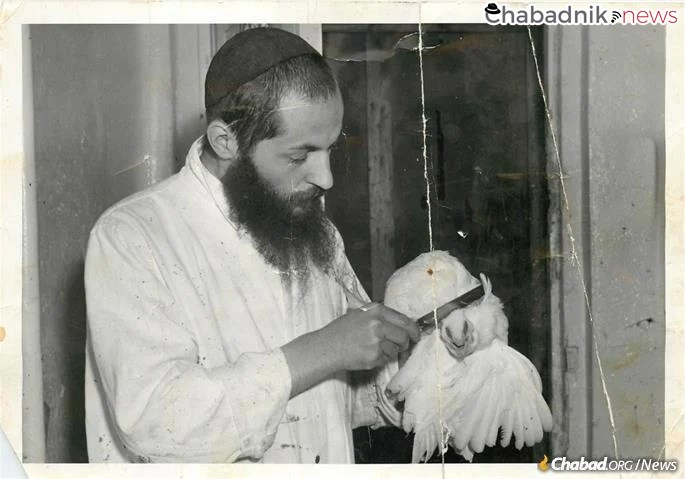

Around that time, Mendel began studying the laws of both kosher slaughter and safrut, the scribal art of writing tefillin, mezuzahs and Torah scrolls. Aronow was trained in safrut in what is known as “the Alter Rebbe’s ksav”—the particular handwriting favored by Rabbi Schneur Zalman, the founder of Chabad. According to tradition, Rabbi Schneur Zalman taught this style to his disciple Reb Reuven Sofer, who also served as his own scribe. Aronow’s teacher in Samarkand, Reb Hershel Lieberman, was the student of Reb Moshe, who was the student of Reb Dodye (Dovid), who had learned from the famed Reb Reuven Sofer himself. Aronow thus served as the link in this unique tradition dating back to the very first generation of Chabad.

Despite the relative calm, life was not simple for the young boy. Several times he was almost drafted to forced-labor battalions, and he had to devise plans for escape on each occasion. Once, he was caught and was already on a moving train when he realized that he did not have his tefillin with him, and would have no way of obtaining a pair. Determined not to miss a day, he jumped off the moving train, miraculously surviving and making it back home with only minor injuries. Later in his life, he would note that nearly all of those who had been taken on the train had perished, and he would attribute his survival to his dedication to tefillin.

Escaping Russia

As the dust settled after World War II, the Soviet Union began allowing Polish citizens to return to their home country. Seeing an opportunity, many Chabad Chassidim forged Polish passports and managed to escape. The Aronow family decided to take the risk as well.

The operation demanded endless ingenuity. Many of the passports were purchased on the black market and listed family members who could travel using the same passport. Every spot on a train could mean another life saved, so a board set out to “create” new families, assigning siblings, children, and at times, even spouses. Mendel’s mother and sister were sent off with other escapees, leaving Mendel to travel on a later train.

Alone, Mendel got to know an elderly woman who was likewise traveling by herself. The woman’s name was Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, mother of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, who later became the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Mendel helped her with her bags and any other way he was able, beginning a friendship that continued until her passing.

Having successfully escaped the USSR, the Chassidim were housed in the displaced persons camp in Poking, Germany. When the opportunity arose to study at the newly established Chabad Yeshivah in Brunoy, France, Mendel traveled with a number of others and continued his Torah studies there.

In 1950, a Jewish businessman flew him and other shochetim from France to Ireland to slaughter cows for kosher meat. While there, a visitor from England brought with him a London Jewish Chronicle delivering shocking news: The Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, of righteous memory—had passed away in New York.

This was devastating news for the entire Jewish world, but was particularly hard on the Chassidim who had escaped the Soviet Union and were now spread around Europe. Ever since the Rebbe had left Soviet Russia in 1927, the Chassidim locked behind the Iron Curtain had been longing for another chance to see him. Now, after they had finally escaped themselves and the goal seemed almost within reach, it was torn away from them.

For Mendel, the experience was even more jarring. Born four months after the Rebbe’s escape, he had only seen a portrait of the Rebbe that his father kept at home. Nevertheless, he considered himself a full-fledged follower of the Rebbe, whom he would now never have a chance to meet.

After the shechita job in Ireland concluded, Mendel traveled to England, and from there to France, hoping to be able to travel from there to America to meet the new Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory. But with no papers, the process began to drag out.

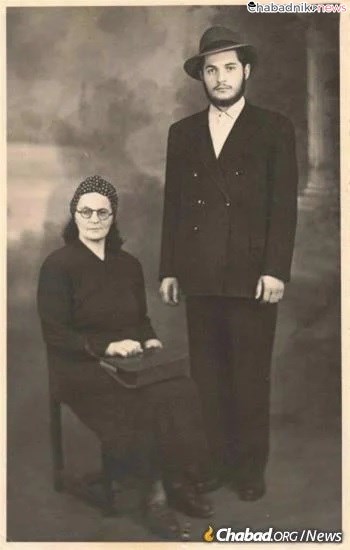

As he waited for his visas, a matchmaker suggested that he meet Golda Minkowitz; a short while later, they were engaged.

A New Life in Toronto

Following their marriage, through Golda’s aunt the couple received a visa to come to Toronto, Canada, and they accepted. After arriving, they were able to sponsor her parents, Rabbi Chaim and Esther Rochel Minkowitz, who followed them to Toronto, where Rabbi Minkowitz became an integral part of the city’s small Chabad community.

At the time, the Chabad community in the city consisted of only a few families. In contrast, Montreal boasted a larger Chabad community, where Aronow would feel right at home. Before making such a big move, however, he wrote to the Rebbe, asking for his blessing and advice. The Rebbe responded to other questions in the letter but did not address the suggested move. The same scenario repeated itself a number of times over the next years. As a dedicated Chassid, Aronow did not even entertain the thought of moving without the Rebbe’s blessing, and remained in Toronto until the day he passed away. Over the next seven decades, he served as a sofer and shochet in the Toronto Jewish community. For many of years, he also ran a small school, in the authentic old style ‘cheder’ method, which met in his house or at a local synagogue.

No matter his position, he remained the same Mendel Aronow that he was in his youth, ready to sacrifice anything for a mitzvah.

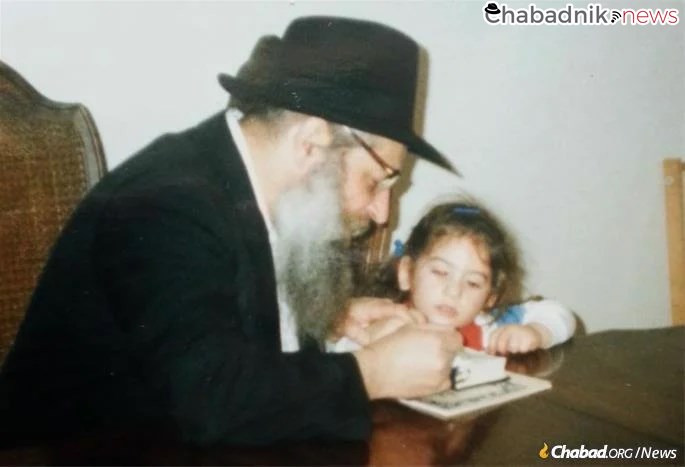

Rabbi Meir Moscowitz, regional director of Lubavitch Chabad of Illinois and a grandson of Rabbi Aronow, remembers him as having a tremendous impact on the education of all his grandchildren.

“He lived to educate; he lived to pass over the Chassidic fire to the next generation,” he said. “On the other hand, he also cared deeply about another Jew’s physical needs, making sure they had everything they needed.”

For years, Aronow ran a small Judaica store. One of his main sources of income was selling Passover supplies, primarily shmurah matzah. Every box of matzah he would sell would make a real difference for his profit margin, which was small even in the best of days.

Despite that all, and despite the fact that he was universally respected, he made sure not to take anyone else’s customers, Moscowitz recalled. Before someone began buying matzah from him, he’d make sure he wasn’t ‘transferring’ from another vendor.

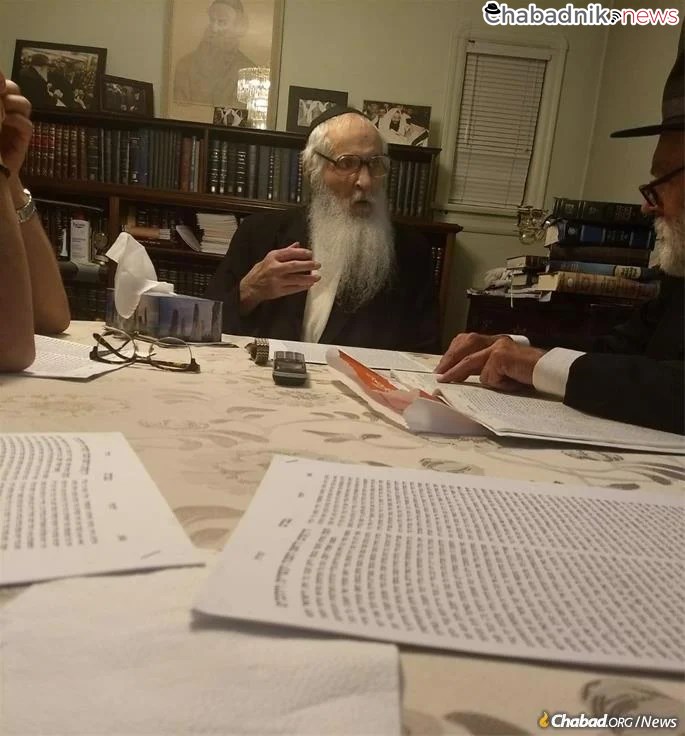

At the direction of the Rebbe, for decades he taught classes in seminal works of Chabad Chassidus like Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s Torah Ohr and Likkutei Torah, alternating between Yiddish, Russian or English depending on the crowd. He would lead farbrengens nearly every Shabbat, and many Toronto residents counted him as their personal mentor.

When Yeshivas Lubavitch Toronto opened up in a former bank building across the street from his longtime home, Aronow took on the role of unofficial mashpia (“mentor”).

Rabbi Akiva Wagner, the yeshivah’s dean, grew up in Toronto, returning to the city in the late 1990s to open the educational center. He described Aronow as a preeminent figure throughout both stages of his life, first in his own education and then in the education of the next generations.

“One thing stuck out when seeing Rabbi Aronow. He was a true Chassid in all his essence, and that came across,” said Wagner.

“The Toronto Jewish community is extremely diverse,” he added. “Nevertheless, Rabbi Aronow was respected across the board.”

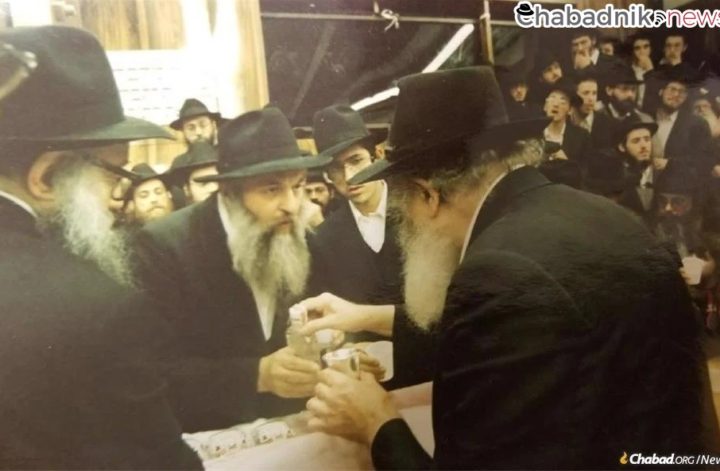

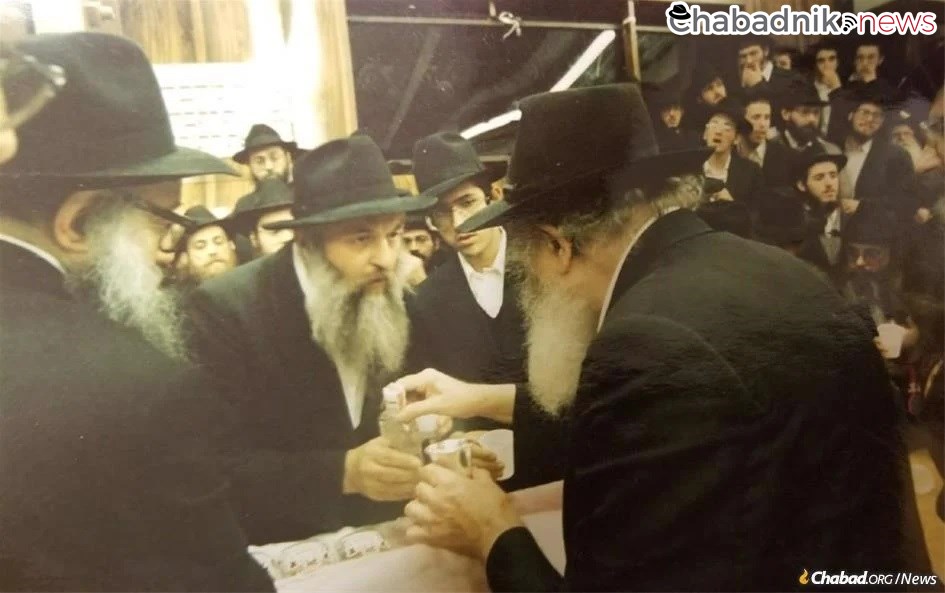

The esteem in which Rabbi Aronow was held by the entire community was on full display at a memorial service held at the end of the shiva. The crowd reflected the breadth of the Toronto community, and the rabbis on the dais represented the spectrum of the Chassidic and non-Chassidic groups in Toronto.

One after another, the speakers spoke about Aronow and the impact he had on them.

Just by “looking at Rabbi Aronow,” Rabbi Shlomo Miller, a prominent rabbinical figure in Toronto and member of the Council of Torah Sages (Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah) of Agudath Israel of America, said at the event, “one was able to gain Yiras Shomayim [fear of Heaven.]”

Rabbi Mendel Aronow was predeceased this year by his wife, Golda, on May 1 (19 Iyar).

They are survived by their children; Mrs. Brina Langsam (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Mrs. Brocha Wilhelm (Toronto, Ontario); Rabbi Yosef Aronow (Kfar Chabad, Israel); Mrs. Esther Rochel Moscowitz (Chicago); Rabbi Zelik Aronow (Florida); Mrs. Shternie Notik (Chicago); as well as many grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren.