A new library’s priceless collection chronicles the nation’s rich Jewish history

The year was 1497. Just five years after leaving his native Spain due to the Edict of Expulsion, Rabbi Avraham Saba stood tearfully beside an olive tree outside of Lisbon, Portugal. There, under what he described as a “tree of tears,” he buried his most precious possession, his manuscript commentary on Chumash, Pirkei Avot, Ruth and Esther.

By that time, the Portuguese had forcibly converted his children to Catholicism under the threat of torture and death, and it was no longer safe for him to own Torah writings or tefillin. Rabbi Saba later tried to exhume his treasure but was caught and imprisoned for six months, before being forced to depart to Morocco on a rickety ship. He was among the lucky ones. Most Portuguese Jews were not allowed to leave, instead forced to live externally as Christians, even as many preserved their Judaism in secret.

Rabbi Saba was never permitted to return to Portugal to recover his manuscripts or his family.

Yet, early one morning in 2017, Rabbi Eli Rosenfeld, co-director of the Rohr Chabad Portugal, received a historic text message from Jimmy Nasser, a resident of Cascais, a coastal village in greater Lisbon: “RABBI SABA IS BACK.”

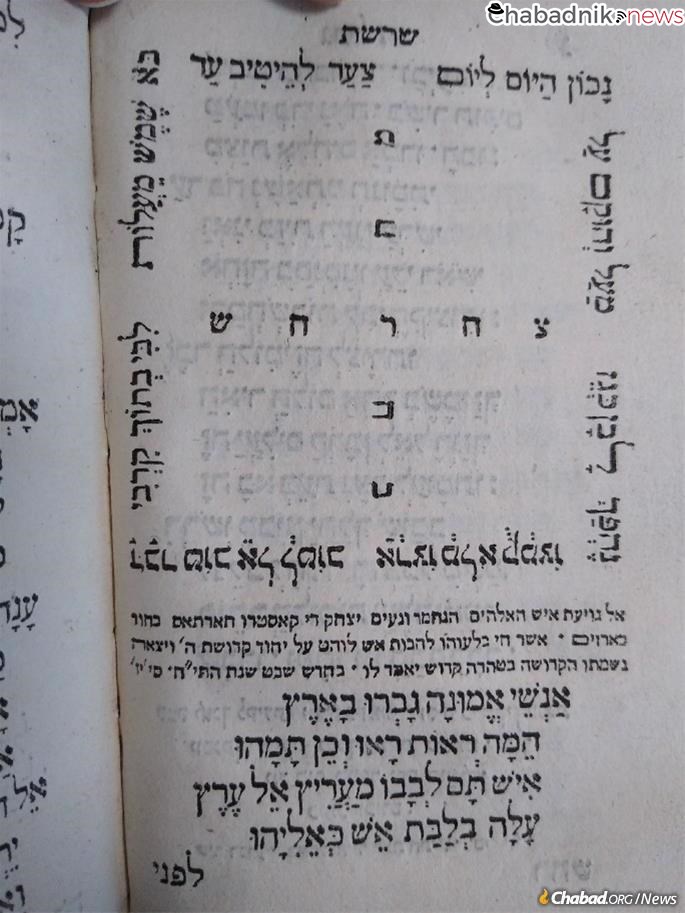

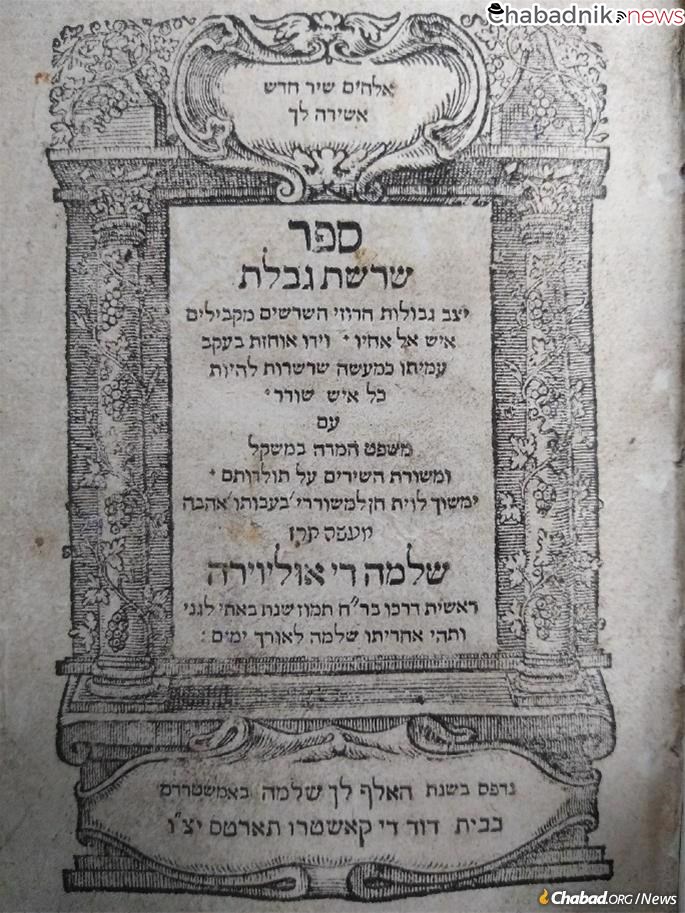

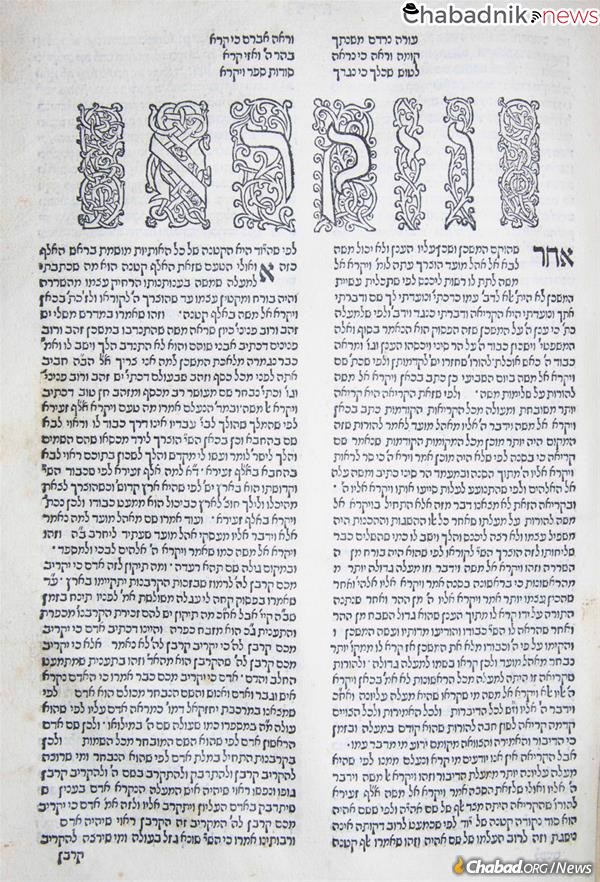

Indeed, the Portuguese Jewish community finally welcomed back the first printed edition of Rabbi Saba’s magnum opus, which he painstakingly reconstructed from memory after arriving in Morocco and was printed in 1523 by Daniel Bomberg in Venice, at the very same time that Bomberg printed his groundbreaking edition of the Talmud.

500 years after Rabbi Saba departed Portugal, broken in body but not in spirit, his life-work returned to Iberia.

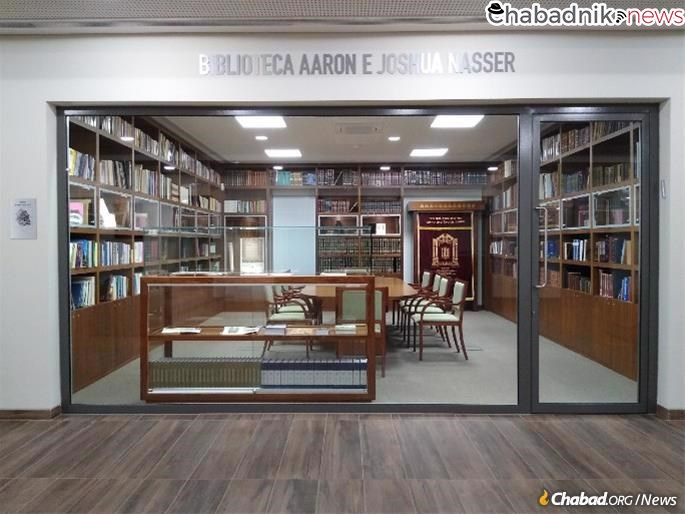

The historic book is one of many that have since “come home” to the Aaron and Joshua Nasser library (named to honor Nasser’s children), in the newly-built Avner Cohen Casa Chabad in Cascais.

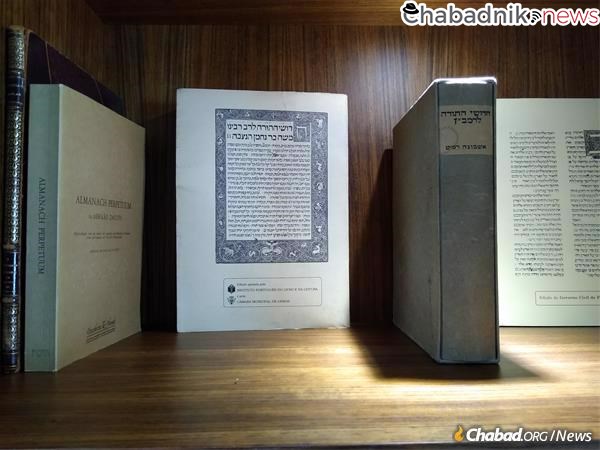

The library, which the results of the efforts of local Jewish families, places special emphasis on Torah works either written by Portuguese Jewish scholars or printed in Portugal, in the brief window between when printing was introduced into the country in 1487 and when Judaism was banned just 10 years later.

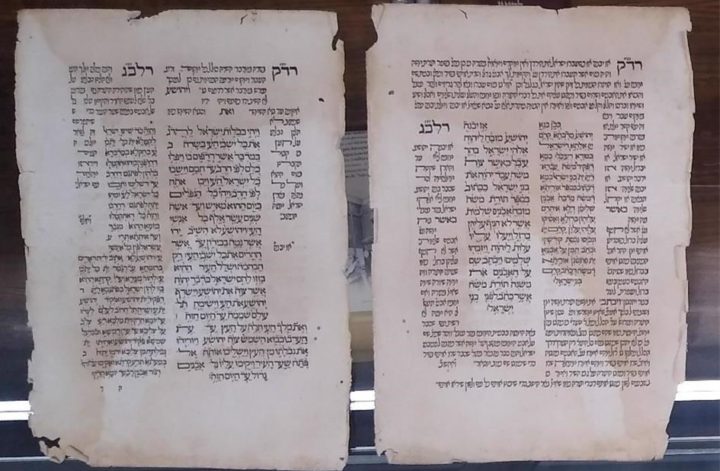

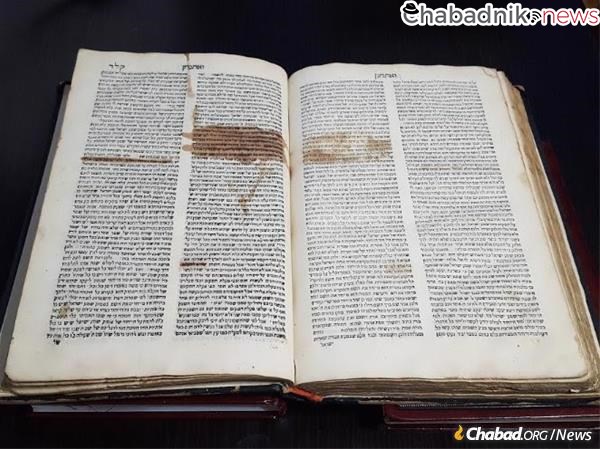

Visitors to the library, which is open to the public, can see the very first book printed in Lisbon, which was the 1489 commentary of Nachmanides on the Torah, as well as a facsimile of the first book printed in all of Portugal, a Hebrew-language edition of Torah, printed in Faro in 1487.

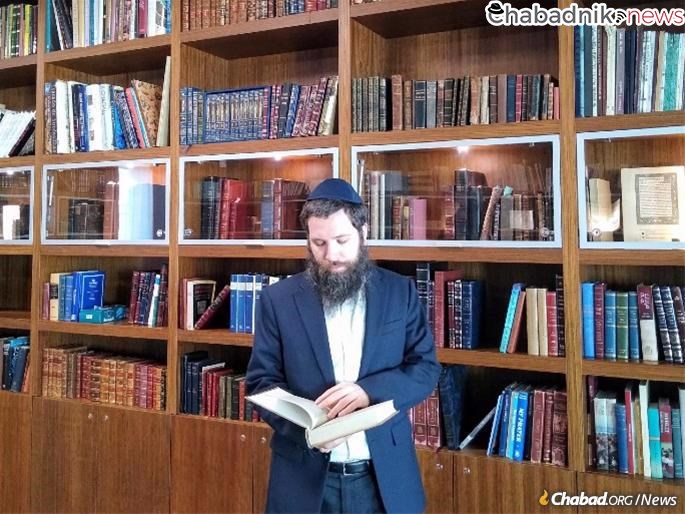

“These books are not just treasures of the Jewish people,” explains Rosenfeld, who regularly gives Zoom tours of the library, which opened its doors in 2020. “These are the very first books printed in our city and in our country, a point of pride for every citizen of our republic.”

As he skillfully guides his Zoom audiences through the treasures of the library, Rosenfeld weaves in anecdotes of Portugues-Jewish history, showing how censors tried to block out passages that were critical of Catholic persecution in Portugal and how the Royal Astronomer to the Portuguese king Rabbi Abraham Zacuto’s works on astronomy were widely accepted by all, and helped guide Christopher Columbus to the New World.

Rosenfeld’s efforts to highlight these efforts has been recognized by the president of Portugal, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, who wrote: “To acknowledge the important historical contributions of Portuguese Jewish citizens, both before and after 1497, is to recognize the Portugal we are today and to recognize that we must be more and more persistent in promoting tolerance, acceptance, and, indeed, complete integration of all, regardless of faith or ethnicity.”

“When my wife and I first came to Portugal from Brooklyn,” says Rosenfeld, a thirty-something with a ready smile and flowing brown beard, “we did not want to import Torah from Israel or the US. We wanted to learn and teach the Torah of Portugal and its scholars.”

Thus began a weekly class on the writings of Don Isaac Abarbanel (the library has the heavily-censored 1551 edition of the commentary on Deuteronomy, which was originally written in draft form in Lisbon) and other Portuguese Torah scholars.

The weekly Torah class and emails soon spawned a book, published in Portuguese and English, called Vozes Judaicas de Portugal or Jewish Voices from Portugal, which the rabbi co-authored together with Rabbi Shlomo Pereira PhD., who was born in Portugal and now lives in the U.S., where he is professor of economics and public policy at the College of William and Mary in Richmond, Va.

The two are currently preparing a second volume for print.

This summer marked 550 years since Portuguese Rabbi Yosef Hiyun completed his commentary on Avot, titled Mil De-Avot. To mark the milestone, the community studied from the work on a weekly basis, mirroring the words written in the preface to the first edition (Constantinople, 1578): “What is the value in all of these wonderful words if they aren’t being heard?”

That message, says Rosenfeld, became his rallying cry, to make the teachings of Portuguese leaders come to life once again.

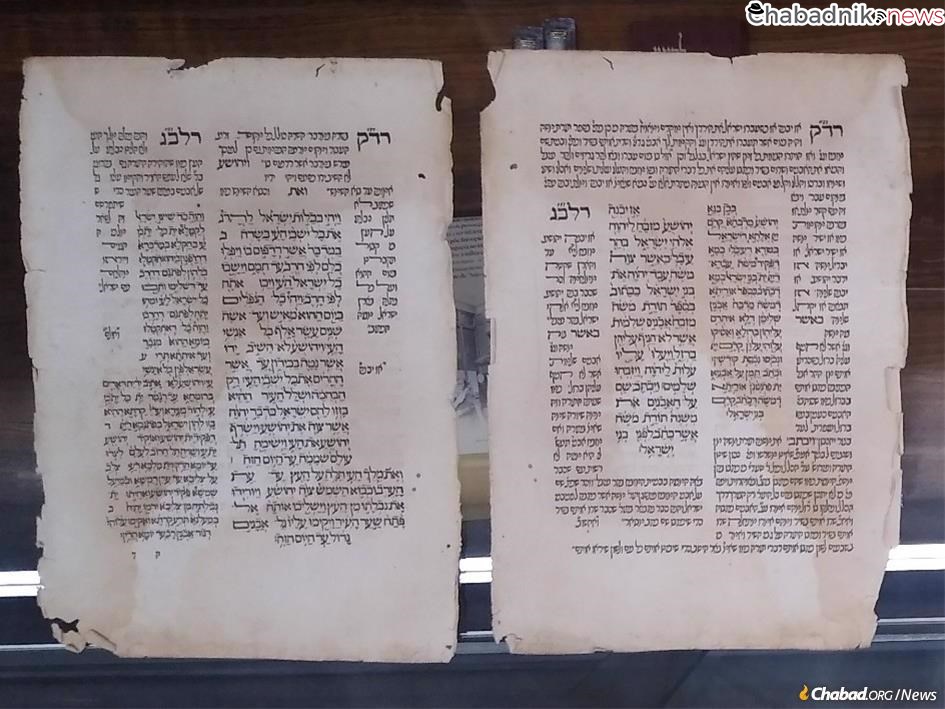

As the rabbi continues to show guests around the library, which includes 16 glass display cases at eye level for the rarest books, as well as dozens of shelves of other books, he pauses to point out two pages from a beautifully laid out edition of the Book of Joshua with the Aramaic Targum and Rashi’s commentary, in a print resembling Sephardic script from the time it was printed in Leiria, Portugal, in 1494.

Later artifacts include a book of poetry written by 17th-century Lisbon-born Rabbi Shlomo de Oliveyra and printed by David Castro in Amsterdam. It features an entry titled “Men of Faith,” memorializing his brother, Isaac Castro, who was caught practicing Judaism in Brazil, then a Portuguese colony, and sent to Lisbon where he was burned at the stake.

But the library tour is far from depressing. Rather, the rabbi uses the books to show how Jews persevered and continued to uphold Judaism in secret for hundreds of years and how Judaism in Portugal is now flourishing out in the open.

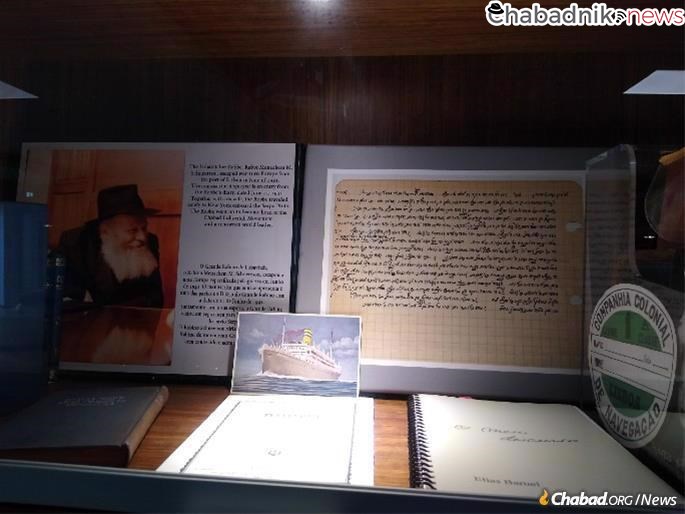

The tour culminates with a facsimile of a handwritten Torah thought penned by the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson of righteous memory—while in Lisbon, having escaped Nazi-occupied France and soon to board a ship to America.

The Rebbe wrote a commentary on the cryptic Talmudic statement that “The Son of David [Messiah] will not come till a fish is sought for an invalid and cannot be found.”

According to Rosenfeld the connection between fish and Moshiach runs deep in the Iberian-Jewish tradition. “The Jews here, who zealously preserved their Judaism in secret, would say that when Moshiach comes, he will need to disguise himself as a fish and swim up the Tagus River because if he were to appear as a man, the Inquisition would surely catch him and burn him.”1

As Rosenfeld set about building the library, he was assisted by many donors, who purchased books and shared from their own collections, especially from the estate of Samuel Ruah, whose family had been stalwarts of Jewish Lisbon for generations.

Yet, for him, the most touching moment was when he woke up to the good news that Rabbi Saba’s book, buried and forgotten under an olive tree outside of Lisbon, had now returned to the country, coming full circle.

Communities wishing to arrange a Zoom tour of the library and glimpse into these precious books can contact Rabbi Rosenfeld at [email protected]. Those interested in in-depth lectures on this era of history can contact Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Pereira at shlomo@chabadofva.org.