The expansion is the latest chapter in the storied collection of Jewish writings

BROOKLYN, N.Y.—The iconic tri-peaked building at 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad-Lubavitch world headquarters, sits at the heart of the sprawling complex of buildings. To its right, the large synagogue and upper-level office rooms and to its left the two smaller homes in the neo-Jacobean style. Connected to 770 by a bridge and underground hallways, these buildings house the Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad and its storied legacy. Home to 300,000 old and rare books, manuscripts and artifacts, the library is one of the largest and most prestigious collections of Judaica, and was deeply cherished by the Rebbes of Chabad.

Tonight, on the eve of 5th day of the Hebrew month of Tevet (which begins this year at sundown on Wednesday, Dec. 8), a small group will officially open a new wing of the library with the affixing of a mezuzah on its doorpost. The date chosen has special significance: On this day in 1987, a Federal court judge handed down the verdict in a legal saga that had dragged on for two years, ruling that the library and its contents belonged to the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

The case had begun when the estranged grandson of the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, had surreptitiously removed 550 books from the Chabad library, later asserting that they were his personal property to sell as he wished. In Judge Charles P. Sifton’s ruling at the culmination of the 23-day trial, these spurious claims were put to bed. “The conclusion is inescapable that the library was not held by the Sixth Rebbe at his death as his personal property,” Sifton wrote in his decision, “but had been delivered to plaintiff [Agudas Chasidei Chabad] to be held in trust for the benefit of the religious community of Chabad Chasidism.”

To the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, the verdict signaled the court’s recognition of the leadership of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—and the fact that the movement continued to thrive under his leadership, long after his predecessor’s passing, contrary to the claims of the defendants. The library wasn’t the personal collection of his father-in-law, the Sixth Rebbe, but, as Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, the Sixth Rebbe’s daughter and the Rebbe’s wife, told the court in a videotaped deposition, “belonged to the Chassidim because my father belonged to the Chassidim.”

In the celebrations following the victory, the Rebbe urged the Chassidim to channel the unbridled joy to concrete action, by buying books, repairing books and most importantly—studying from them. “According to Torah,” the Rebbe declared the following year on the first anniversary of the monumental ruling, “the victory of holy books … is by using them and learning from them even more—the more they are used, the more dignity they have, even if they become worn out and torn from use.”

Library Founded by the First Chabad-Lubavitch Rebbe

The library’s history begins with the first Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1813) and grew in size with each subsequent Rebbe. Over the centuries, the library weathered fires, Communism and Nazism—the latter confiscating it for future display in their museum of the Jews. Echoing Jewish survival itself, the priceless treasures lived on, only growing in size.

With the outbreak of World War I, the fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Shalom DovBer of Lubavitch, sent a large part of the library to a storage facility in Moscow, which was then nationalized by the Bolsheviks. A smaller number of valuable manuscripts and books remained with him.

Much of the original collection was lost, but the fifth Rebbe’s son, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, a passionate bibliophile, worked hard to rebuild it, and by the time he was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1927, had amassed a large collection. It accompanied him to Riga, Warsaw and Otwock, Poland. Following the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Rebbe had part of it transferred to the American Embassy in Warsaw for safekeeping, while the remainder was left in Otwock.

When Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak arrived in the United States from war-ravaged Europe on March 19, 1940, he brought with him only two suitcases of the most precious writings. The rest either stayed in Poland or made their way to Russia after the Red Army invaded Germany. Part of the library was sent from Otwock to New York in 1941, a year after Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s arrival, by his son-in-law, Rabbi Mendel Horenstein, who was later killed in Treblinka along with his wife, Rebbetzin Sheina. A large portion remained in Poland, and after years of diplomatic efforts, Poland returned the books in 1977.

But Chabad has never given up on retrieving the parts of the library confiscated by the Bolsheviks. Indeed, the library’s director, Rabbi Shalom Dovber Levine, himself spent a year-and-a-half in Moscow after Perestroika working to retrieve the books. Just prior to the Soviet Union’s dissolution a Soviet court ruled that Chabad’s library must be returned to the movement, but its order went unheeded. To this day, 10,000 books belonging to the Library of Agudas Chasidei Chabad remain imprisoned in Russia.

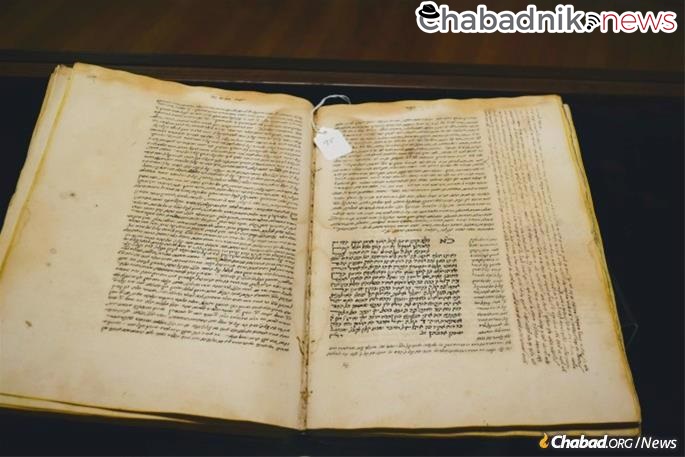

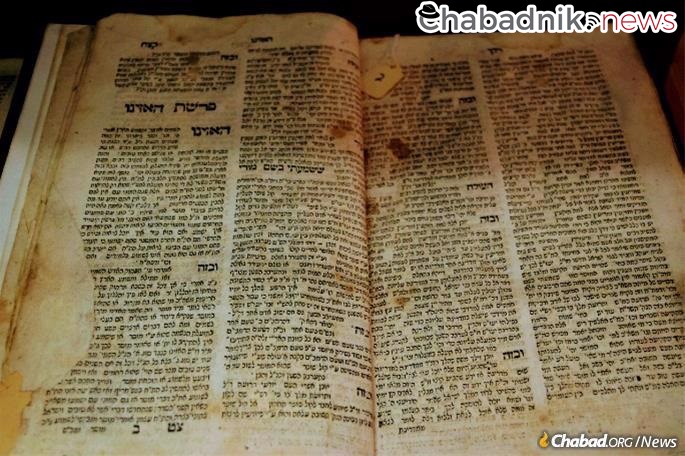

Volumes Date Back to the 14th Century

Today, the library is home to rare and precious books and artifacts, including manuscripts dating back to the 14th century. “The first dated Jewish book printed is Rashi’s commentary on the Chumash,” notes Levine. “It was printed in 1475. We have several pages of it.” The library also has a copy of the first book of Chassidic thought ever printed: “The Toldot Yaakov Yosef was printed in 1780 and we have a book of that first print,” Levine tells Chabad.org.

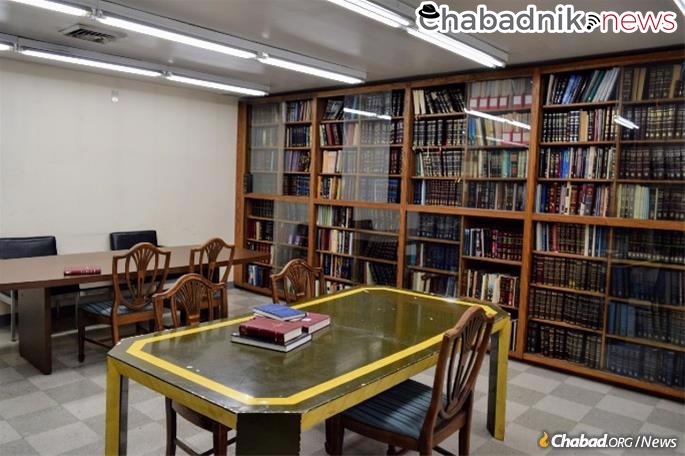

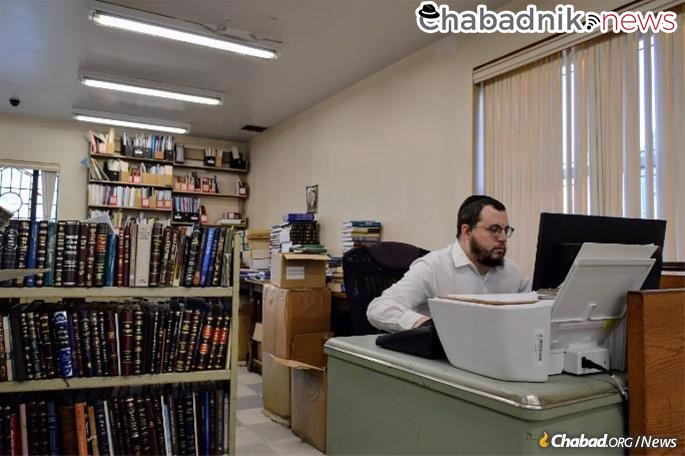

Chabad’s library and its website have become a haven for researchers and historians, with a trove of books and manuscripts available to view at its reading room, while large quantities of the archives have been scanned and made available online. Thousands of pictures of Chassidic life in the 20th century have been uploaded as well, making this communal treasure truly accessible. At the library’s third floor exhibition room, many historic items are on display, with guided tours available upon prior arrangement.

The library doesn’t purchase books, rather they are gifted copies by authors, scholars and collectors. Some members of the public will even scour Judaica auctions on the lookout for old books to purchase for the library, Levine notes. “Many of those who contribute items don’t have a direct connection to Chabad, they simply admire the library,” explains Levine.

A Priceless Collection of Books and Judaica

The constant influx of books means that the library has been in an almost perpetual state of expansion since moving to the U.S. in 1941, when the collection of 50,000 books was housed in 770’s basement floor. The Sixth Rebbe continued to expand the library, and at the time of his passing in 1950, he had nearly doubled the collection. His son-in-law and successor the Rebbe continued growing the library, and in 1956 Chabad-Lubavitch purchased the next-door building at 766 Eastern Parkway, and an entire floor was dedicated to the growing library, housing another 20,000 books.

When the Rebbe appointed Levine to begin working in the library in 1977, “the floor dedicated to the library was packed to capacity, with many books still lying in boxes,” he recalled. The bottom floor was then also designated for the books, and after several years, it too, was filled to capacity. In 1980, a further wing was added, converting the garage into library space. With the Rebbe’s blessing and guidance throughout, more work was done expanding the library space in 1984 and again in 1987.

On the first anniversary of the 1987 verdict, the Rebbe called for authors, publishers and collectors to contribute to the library. The response was enormous, and once again, the library had outgrown its shelves, with thousands of books sent in from all over the world. In 1989, a massive expansion was made, with construction taking place under the courtyard between the two buildings to create a large storage space for the now 250,000 books.

That additional space lasted two decades and about 30,000 more books, until the hallways and stairwells began to fill with boxes in 2010. With the help of Israeli philanthropist Yitzchak Miralashvili the neighboring building at 760 Eastern Parkway was purchased, with the intention of using the top floor as library space. With the support of local philanthropist Yossi Popack, the top floor was recently gutted and renovated and today is home to a temperature-controlled library room with capacity for 25,000 additional books. The books are currently being unpacked and processed.

What will be when this space no longer suffices? “We will use the other floors of this building,” Levine says.

Thirty-seven years after an episode that threatened the existence of the library, and following a protracted legal battle, the library continues to amass a priceless fortune of books, the heritage of all Jews around the world.