Fluent in four languages, she kept an open home and heart for all

Long before she got married in the summer of 1989, Myriam Bentolila knew that she wanted to serve as a Chabad-Lubavitch emissary. That’s the life she had grown up on in Milan, Italy, where her parents were sent in the early 1960s by the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—and the one her young husband, Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila, sought as well. Even if it meant Zaire, Africa.

“When I told my wife we were offered to go to the Congo—Zaire at the time—she just said, ‘Great, Africa looks interesting, let’s go,’ ” remembers her husband. “She didn’t ask to see the place first.”

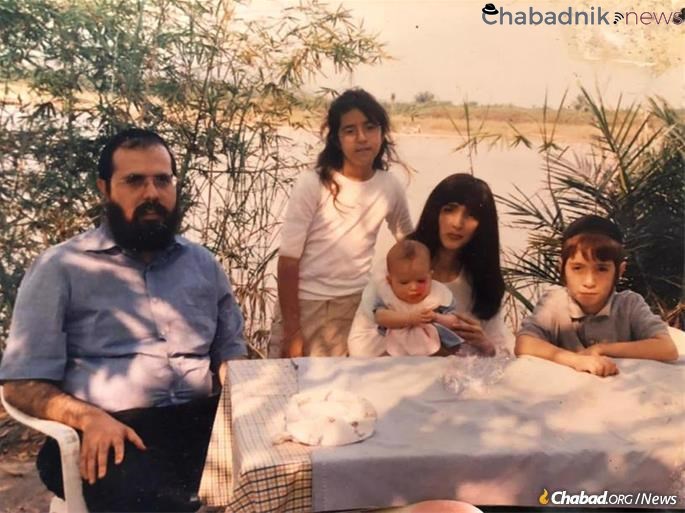

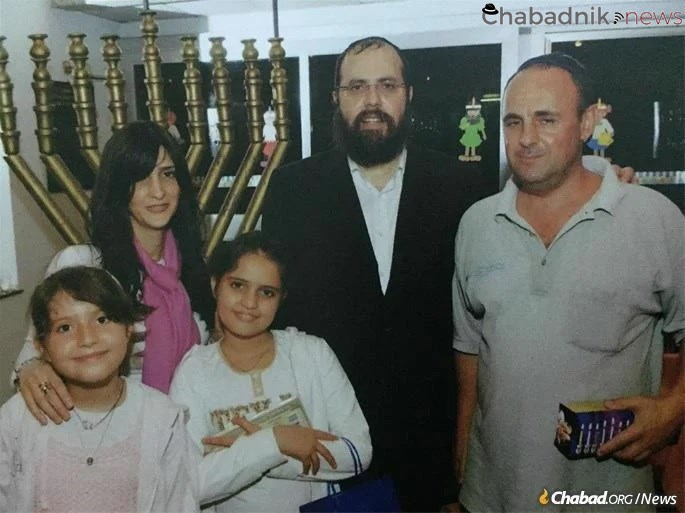

The Bentolilas received the Rebbe’s blessing to open Chabad-Lubavitch of Central Africa on the second-to-last night of Chanukah 1990. Less than a month later, together with their 3-month-old daughter, they struck out for the Congo’s capital, Kinshasa. Myriam Bentolila, who passed away after a lengthy illness on April 1 (the eve of 20 Nissan) at the age of 52, would dedicate the next 30 years of her life to sharing the beauty of Judaism with every person she encountered.

“The first time I met her was when we went to Chabad on Shabbat,” recalls Ronit Blei Weingarten of Givat Shmuel, Israel. It was the summer of 2015, and she and her husband, Shlomo, had just arrived in Kinshasa, where they would spend a year-long stint for her husband’s job. “After the Friday-night meal she asked us where we were staying, and I said we were walking back to our hotel. She said ‘From now on, you stay with us.’ For the next year, we slept and ate at her home every single Shabbat.”

The relationship they would form over the next year, says Blei Weingarten, was intense and multifold. “The Congo is extremely lonely,” she explains. “The rabbanit was a friend, a mother, a sister—every female figure in my life in one.”

“Rebbetzin Bentolila epitomized what it meant to be the Rebbe’s emissary,” says Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, vice chairman of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the educational arm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. “She was dedicated to her community, to her family, to her husband, but above all to the Rebbe and his vision. She didn’t need or ever want accolades, but in her own strong way, she contributed to changing the meaning of Jewish life in Africa. Her physical presence will be missed, even as her impact on the lives of countless will continue.”

“Here was this Italian lady, delicate, chic, stylish—the most fashionable lady in the Congo,” adds Blei Weingarten. “She was open-eyed about the difficulties she lived with, but this is what she gave her life for, and she stayed there for 30 years.”

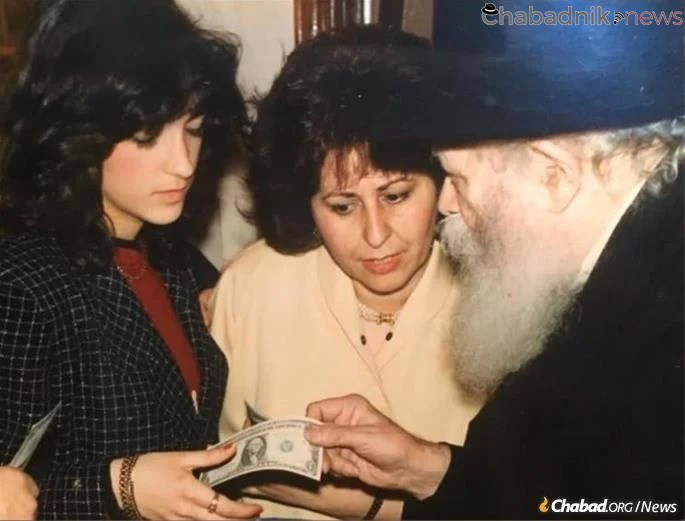

A Chassidic Childhood in Milan

Myriam Bentolila was born on April 25, 1968, in Milan, Italy, the third of Rabbi Yeshua and Rachel Hadad’s eight children. Her parents were both Moroccan-born Sephardic Jews who had been reached early in their lives by Chabad’s educational work, Rabbi Hadad studying at the Lubavitcher yeshivah in Meknes, Morocco, before going on to learn in Paris and New York, and Rachel in France. They married in Milan in 1962, with the Rebbe personally arranging for a member of Milan’s Jewish community to pay for the wedding expenses.

The couple served as Chabad emissaries in Milan for the next five decades with Rabbi Hadad leading the Sephardic Synagogue of Via Guastalla and opening a network of Talmud Torahs geared at Sephardic children. Once, when he brought an album to the Rebbe with pictures and the names of close to 200 students, teachers and courses of study, he watched as the Rebbe carefully looked at each name and smiled. Then the Rebbe turned to him and asked: “What am I guilty of that I didn’t know about this until today?”

This would be a lesson Myriam Bentolila took to heart.

“She wasn’t a shy person, but she didn’t want publicity or the spotlight,” recalls her daughter, Debbie Bensaid. “If people asked her where she was from, she’d always say Italy. She knew if she said the Congo, people would make a big deal of it. She felt the only one who needed to know about her work was the Rebbe.”

After studying in Chabad’s school in Milan, Bentolila attended Beth Rivkah in Paris. In 1989, she met Moroccan-born, Montreal-reared Shlomo Bentolila, and the couple married in Italy. Rabbi Bentolila had previously traveled to central Africa in order to bolster Jewish life there as part of Chabad’s Merkos Shlichus (“Roving Rabbis”) program. Not long after their marriage, Rabbi Bentolila was offered the position of rabbi of the Jewish community of Kinshasa and the opportunity to open a permanent Chabad presence serving dozens of countries throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, with the exclusion of South Africa.

The young couple wrote a note to the Rebbe stating they had one year of financial backing, the permission of both sets of parents, and that they were ready to move there with full and open hearts. The Bentolilas received the Rebbe’s consent and blessing the very next day, and on Jan. 16, 1991, they headed off to open a new chapter of Jewish life in central Africa.

Planting Jewish Roots in the Congo

The country then called Zaire had been home to a Jewish community dating back prior to independence, when it was known as the Belgian Congo. “Until the 1970s, Zaire’s Jewish community was centered in the city of Lubumbashi,” a 1995 Jewish Telegraphic Agency profile of the Bentolilas explained. The first Jews came from the Greek island of Rhodes, Egypt and Turkey, later joined by their French-speaking brethren from Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. By the early 1990s many Jews were leaving, but far from everyone.

Phillipe Hasson was one of these Congolese Jews, born in 1957 in the southern city of Kalemie, then Albertville, on the shore of massive Lake Tanganyika. When violence struck his hometown in the aftermath of the country’s independence, his family moved to Lubumbashi, while he was sent to a Christian boarding school in South Africa. By the time the Bentolilas arrived in the country, Hasson was back in Lubumbashi and president of its rapidly dwindling Jewish community. When the new rabbi, his wife and their baby daughter came to the city to organize programming for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur that first year, they stayed at Hasson’s home and a relationship formed.

“They were a young couple then, but they made a great impression on everyone,” recalls Hasson. Later, when Lubumbashi fell victim to street violence and looting and Hasson lost his businesses, he moved with his family to Kinshasa.

“We became the best of friends; I felt like a brother,” he says. “Myriam knew everything about me, about my family; she was always there for all of us.”

Hasson later moved to Israel, returning to Kinshasa for business reasons. “Sometimes, I would spend a month in their house, and I never felt uncomfortable there. The way she treated everyone, big or small, was unbelievable,” he says. “Their home was always open to everyone at all times. That was her.”

Though Bentolila was involved in many aspects of running the Chabad center in Kinshasa, she saw her primary role as a homemaker, keeping an open home for community members and travelers, caring for and educating her children, and supporting her husband as he traveled to the more than one-dozen African countries served by Chabad of Central Africa. Despite her behind-the-scenes demeanor, she lived with her deeply held values and was never reluctant to say so.

“When she believed something was right, she wouldn’t budge,” says Blei Weingarten. “She personified midat ha’emet, truth, and she wasn’t afraid to express it.”

“Those were two pieces of advice my mother gave me,” says Bensaid about a conversation they had before she and her husband opened Chabad of Ivory Coast in 2018. “She told me to welcome everyone, no matter what, and to never allow myself to be stepped on. Always stay true to yourself, to the ways of the Torah, and don’t hold back when it comes to something you believe in.”

An Often-Dangerous Vigil on a New Continent

Life in the Congo wasn’t always easy, especially in the beginning. The Bentolilas headed out to Kinshasa with little fanfare in an age before widespread internet or anything resembling WhatsApp. In the beginning, the only way Myriam could stay in touch with her parents and family—with whom she was forever close—was via pay phone.

For a while, they lived in a tiny two-bedroom apartment before moving into a larger and more secure home in the synagogue compound. The country was plagued by electric blackouts, and even once they got a generator, there was no guarantee it wouldn’t blow. The 1995 JTA profile describes Myriam going shopping with stacks of bills filling her purse due to the rampant inflation hitting then-Zaire’s currency.

And then there were the wars and violence. Prior to their first Passover in Kinshasa, Rabbi Bentolila was stopped by soldiers as he delivered shmurah matzah in the city. They let him go after he paid a bribe—and shared some of the matzah. Violence rocked their home city in 1991 and 1993. Then, in 1997, came a coup. “About a dozen Jews ate their Friday night meal at the home of Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila … ” the JTA reported at the time, “the sound of heavy artillery boomed overhead and sporadic shooting was heard echoing throughout the city.” That’s when Zaire became the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as it is formally known today. A second Congolese war the next year forced the Bentolilas to leave the country together with most of their community, returning when things quieted down.

Throughout it all, Myriam Bentolila kept at the mission she was sent on. In the days before online schools, she and her husband taught their children at home before sending them abroad to study at Chabad schools. “It was obviously difficult for her,” says Blei Weingarten, “but that her children should continue on this path was the most important thing for her.”

Then there was holding down the fort while her husband traveled, bringing Jewish life to the rest of the continent. Today, there are 11 permanent Chabad centers under the auspices of Chabad of Central Africa, including in Angola, Nigeria, Ghana and Uganda, with plans recently announced for a center in Zambia. Today, Rabbi Bentolila says none of it could have happened without his wife’s strong support.

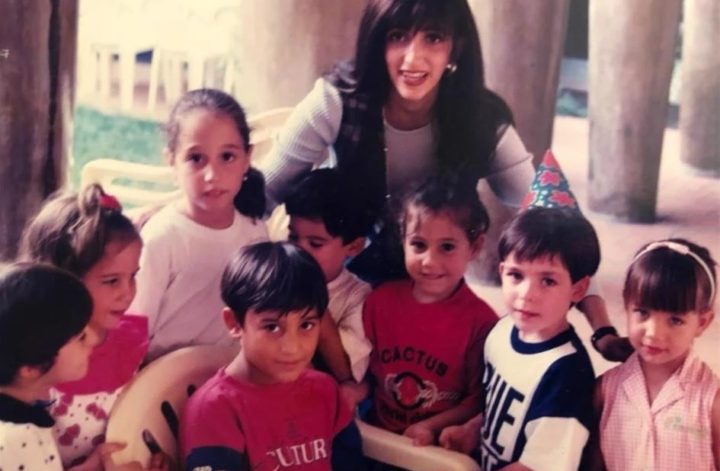

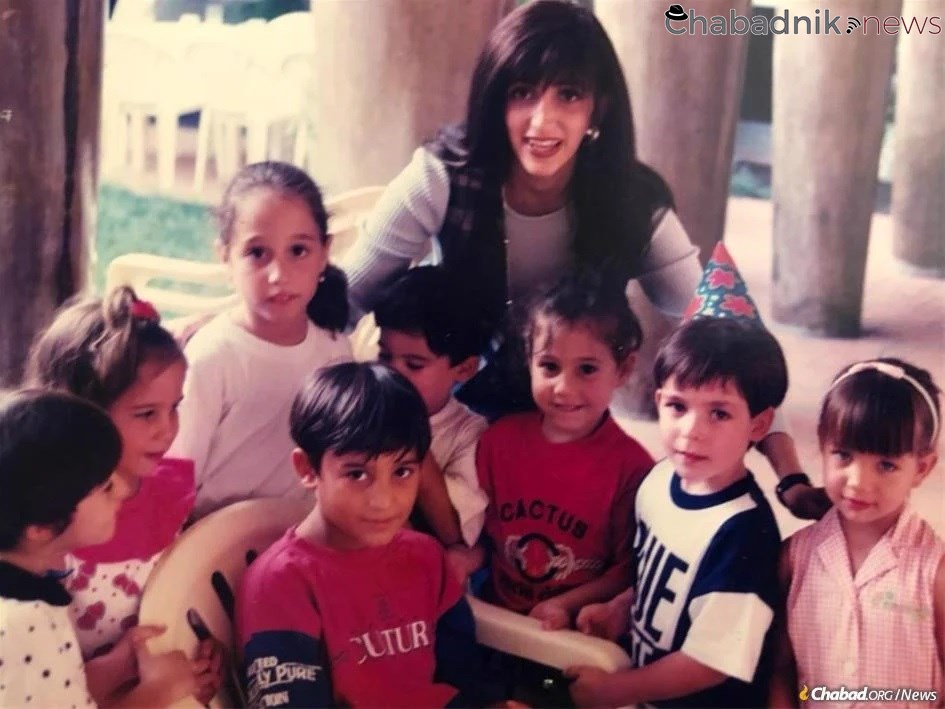

Well-read and educated—she spoke four languages fluently and taught university-level Italian in Kinshasa—she poured much of her efforts into education. At the outset, Kinshasa was home to hundreds of Jewish families, and, knowing it might be many of the childrens’ only exposure to authentic Judaism, she worked hard to build the best Hebrew school possible. Bensaid only realized how advanced her mother’s Hebrew school was recently, when she spent a few months back in Kinshasa while her mother was in treatment in Israel.

“Her curriculum isn’t light at all; it had proper prayer, history, Hebrew grammar—it was very rich,” she says. “The mothers told me they loved how she taught their children. She took it so seriously.”

“I got the chance to know Myriam better when she started teaching my boys at the synagogue,” says Nathalie Beebee, an Israeli living in Kinshasa. “Myriam had a passion for Judaism and an ease to teach Hebrew. She had a special patience for children and knew just how to get them to listen and love everything that made us Jews.”

It was never about numbers either, and even as the Jewish demographics in Kinshasa shifted and there were less young families with children of that age, she never called it quits. “It didn’t matter if she was teaching 20 children or three,” says Bensaid. “The classroom was set up perfectly, and she was there to teach.” From her hospital bed in Israel, Bentolila gave Bensaid instructions on how to work with each child and asked for updates on their progress.

“Now my boys have a keen interest to study our holidays, traditions and learn Hebrew … ,” adds Beebee. “We will miss her and never forget her.”

Blei Weingarten says that during the year she spent in the Congo with Bentolila, she got to observe Bentolila up close as a mother, wife and emissary. She saw her attention to detail in the events she put on and the people she interacted with. They discussed everything, too—aside for her role as a shlucha, as an emissary.

“We never spoke about it because she lived shlichut from the moment she woke up to when she went to sleep in the evening,” says Blei Weingarten. “She taught me many things: Tanya, niggunim, about 19 Kislev and Didan Notzach. But her biggest message was that shlichut is a state of mind. I can be an emissary even in Israel, even if I am not officially Chabad. We all need to open our eyes and see the work we can do and the influence we can have in our situation.

“This was the core of who she was.”

Bentolila is survived by her husband and their children: Debbie Bensaid (Abidjan, Ivory Coast), Binyamin Avraham Bentolila (Paris), Chaya Mushka Nemni (Milan) and Sosha Bentolila (Kinshasa), as well as grandchildren.

She is also survived by her mother Rebbetzin Rachel Hadad; and her siblings Rabbi Menachem Hadad (Brussels, Belgium), Chana Hadad (Milan), Sara Hadad (Jerusalem), Rabbi Yosef Hadad (Milan), Rabbi Michael Hadad (Brooklyn, N.Y.), Avigayil Dadon (Lod, Israel), and Eliyahu Hadad (Milan.)