“My zaidy called it ‘di heiliger Shabbos’ (the holy Shabbos); my father called it the Shabbos; I call it ‘the Sabbath,’ my children call it ‘Saturday,’ and my grandchildren call it ‘the day before Super Bowl Sunday’.”

This pithy anecdote describes a tragic trend among Jews who came over from the Old World and failed, for whatever reason, to transmit di heiliger Shabbos to the younger generation. It tells of its disappearance not only from the lived experience — but also from the lexicon — of Jews who have assimilated into secular culture.

But Shabbos is embedded in the Jewish soul. Some people hold on to it at all costs, while others come back to it after generations of nearly losing it. These are the personal Shabbos stories of an eclectic group of influential personalities.

Part 4/7

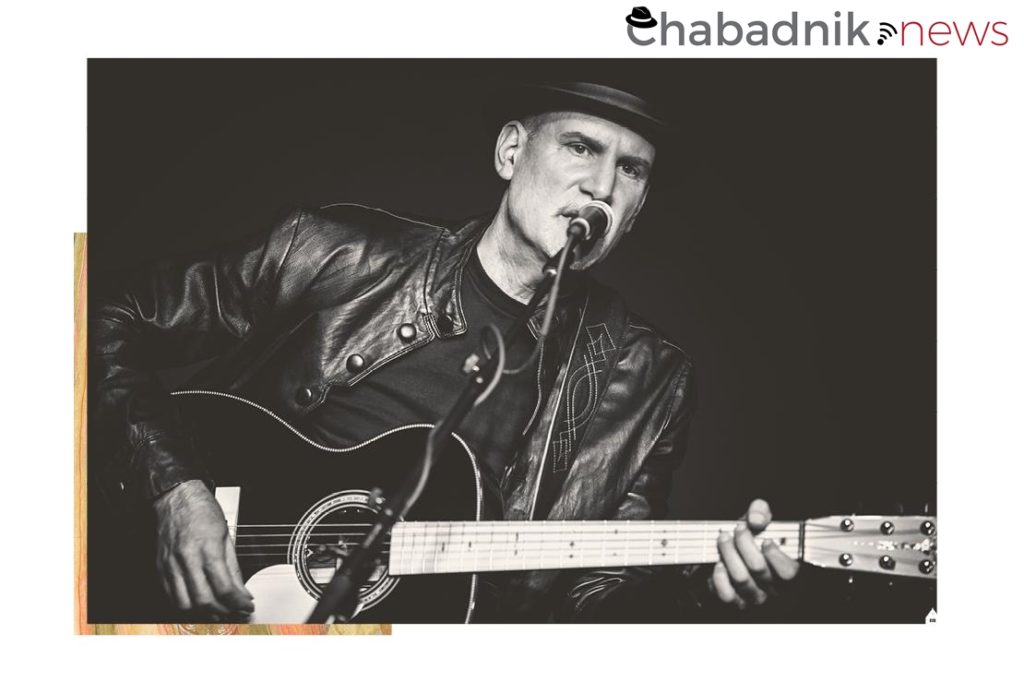

When I was first signed to Island Records in 1986, as now, the most effective way to promote a new act was to have them open shows for a more established artist. Lou Maglia, Island’s new president and the man who signed me to the label, had been considering a few names for me — Sting, for instance, but also Joe Cocker and some others. When I walked into Lou’s office and closed the door behind me, I was about to forego each of those opportunities in a single fifteen-minute meeting. “Lou, I’m starting to keep this Jewish thing called Shabbat and I won’t be available to perform on Friday nights any longer.”

Lou looked at me for a moment and just belly laughed. Not to be cruel or condescending. Lou simply had no language, no context for what he’d just heard. He assumed I was joking. And it was funny. Why would an artist who had worked so hard to get to this point in his career tell the president of a major record label that he wouldn’t work on Friday night — the most important show business night of the week?

Only after getting a record deal — something I’d thought about nearly every day since I was thirteen years old — was I able to see it for what it wasn’t. It wasn’t the answer to my hopes and dreams, and it surely wasn’t going to make me into something more than I already was. Shabbat, on the other hand, felt huge. Transformative.

It also spoke to my rebellious nature. A few months into dealing with the marketing people at the record label, the penumbra faded. I saw that rock and roll’s so-called rebellious spirit was just a bunch of hype. Finally behind the curtain, I could see how limited my lifelong dream of getting a record deal was. I was quickly becoming another commodity. Shabbat, by contrast, was the ultimate countercultural act. It made me feel as though I were in lockstep with G-d. As if I was tasting a modicum of transcendence — something that, for me, could only come about from being in service to a Force infinitely larger than myself. Shabbat was (and still is) my day of arrival. It presented me with a break in time, a respite, in which I could feel viscerally that — for twenty-four hours, at least — I was no longer wandering. No longer lost and insatiably hungering for more and more impermanent things.

That idea of “arrival” hit me hard as I walked the streets near Times Square on one of my first Shabbats. Everything and everyone seemed to be in a mania of motion. In the most profound and pleasant way, I felt that I was walking in a kind of insulated bubble of suspended time. My weekday concerns had dissipated. The constant grind of promoting my music, writing new and better songs, and getting a firmer foothold in the music game came sputtering to a halt. It was on that walk, and others like it, that I was able to gain a more clarified picture of my place in the world, and to take stock of who I was becoming as a son, as a friend, and as a man.

In the spaces that Shabbat began to provide, the things that would later become my life priorities took on a new resonance. It became harder for me, for example, to continue to believe that I could forestall getting married and setting up a Jewish home, even if on the surface those things appeared to conflict with my career goals. In time, the apparent conflicts dissipated as well.

And today, the more often I “arrive” in the bubble of Shabbat, the more my observance becomes a personal testimony to my ever-growing trust in the Oneness of G-d.

Grammy- and Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter Peter Himmelman is a visual artist, author, film composer, entrepreneur, and rock and roll musician. Himmelman has taken his special skills at unlocking innate creativity to academic institutions such as The Wharton School of Business at The University of Pennsylvania, The UCLA School of Medicine, as well as corporate behemoths like Boeing, Adobe, and Gap Inc. His most recent book, Let Me Out: Unlock Your Creative Mind and Bring Your Ideas to Life is the compendium of his novel methods of helping people discover their most creative selves.

Source: https://www.lubavitch.com/my-day-of-arrival-peter-himmelman/