New volume spurs worldwide study of Shaar HaBitachon (‘The Gate of Trust’)

When Esther Hecht walked into a Judaica store during a recent visit to Brooklyn, N.Y., she laid eyes on a book that seemed to be pulling her in. The book was titled Shaar HaBitachon: The Gate of Trust.

Hecht was on a visit to New York from South Africa, where she lives and teaches women’s Torah classes at Chabad-Lubavitch of Sandton, South Africa—a suburb just north of Johannesburg where her parents are Chabad emissaries. Leafing through Shaar HaBitachon, Hecht thought of the Jewish community back home in Sandton. In the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, she had heard so many of them ask the same major question: How was an individual meant to interpret and understand the way the world had turned upside down? People were grappling with loss of loved ones, financial stability and certainty. It was a question she had found herself asking as well.

Hecht knew those around her needed support, and she knew a class about trust in G‑d would be helpful. As she stood in the Brooklyn Judaica store holding Shaar HaBitachon: The Gate of Trust in her hands, she felt the dots connect. Bitachon—translated mostly as “trust” and connoting a sense of optimism and confidence based not on reason or experience but on faith—was something she felt she needed as much as those around her in Sandton did. She decided she was going to teach this as she learned it.

“If someone tells you that they don’t struggle with their ‘trust,’ they are not telling you the truth,” Hecht observes. “Everyone has questions, we are all human. Once I realized I could be vulnerable about that, I realized I could teach this class.”

When she arrived back home in South Africa, she put out a call on her Instagram, sharing that she would be studying this book and anyone that wanted to join her was more than welcome over Zoom. Some 25 Jewish women from all backgrounds joined her each week.

Word by word, these women have been exploring what it means to trust in G‑d. The group has created a safe space where struggles can be shared, and personal connections are strengthened as real and raw matters of faith are discussed. Hecht began hearing feedback from those who were learning with her; they felt a new, deep sense of calm. It was resonating.

The Gate of Trust is not a shiny new self-help manual found on the shelves at major bookstores. In fact, the text, written by 11th-century Spanish scholar Rabbeinu Bachya ibn Pekuda, is almost 1,000 years old.

Its message is needed now more than ever.

‘What Room is Left for Worry?’

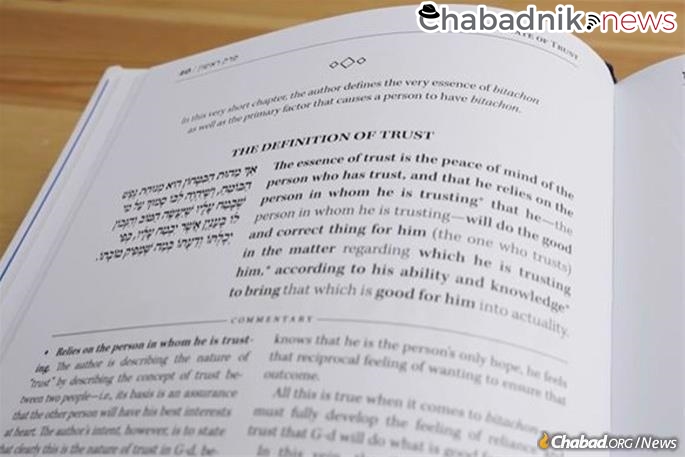

Rabbeinu Bachya’s The Gate of Trust is part of a 10-part series he wrote titled Chovot Halevovot, “Duties of the Heart.” Written originally in Judeo-Arabic during a time when contemporary scholars were producing works concentrating on the practice, law and ritual of Judaic observance, Rabbeinu Bachya’s series focused instead on one’s inner relationship with G‑d.The work had a deep impact on the Jewish world, and beyond, and throughout the centuries various scholars have elucidated what one can learn from this ancient text.

Summarizing Rabbeinu Bachya’s thesis, Hecht explains that the first part of the process is understanding that “true trust is partnering with G‑d. I am doing my part and I completely trust G‑d will do His. Day to day, I stress less because I know that my partner is G‑d, and He is the only one who truly knows what is good.”

But Rabbeinu Bachya continues, explaining that it’s not just about trusting that what we are seeing is good, but that our trust itself will produce positive results in the way that we seek to experience them.

The original text, translated into Hebrew by the famed translator Rabbi Judah ibn Tibbon around 1180, can be difficult to process, causing readers to spend more time parsing each word and leaving less time to implement the lessons being learned.

In a 1955 letter discussing whether school-age students should study Chovot Halevovot, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, underlined that it needed to be accompanied by a competent commentary. “If the material is presented literally … it will be difficult for [the students] to understand, it depends on the manner of explanation, and often, the explanation is key … .”

Nevertheless, the Rebbe would often tell those who turned to him with struggles to take time to carefully study the book and internalize its lessons. Especially during difficult times, the Rebbe explained it is necessary to give the study “practical application.” “You should study, three or four times over, Shaar HaBitachon in Chovos HaLevavos,” the Rebbe wrote to someone facing a medical situation in 1951.

To a community rabbi experiencing “bitterness and melancholy” and wishing to seek a different position, the Rebbe was unequivocal: “You ought to remain in your present post, and to trust firmly that G‑d will lead you in the path of truth … ” Should doubts on this enter his mind, the Rebbe added, “this does not indicate a doubt as to your ability, but a weakness in your trust. The remedy for this is to study Shaar HaBitachon in Chovos HaLevavos … .”

Guiding another individual struggling with worries and stress, the Rebbe counsels him to “cultivate the attribute of bitachon,” as explained in many works, “including Chovos HaLevavos, Shaar HaBitachon.” One must realize that G‑d—the essence of good—supervises every person with individual divine Providence, the Rebbe explained, “if so, what room is left for worry?”

“I always looked at it as either you’re good at bitachon or you’re not. But what I realized this year is that bitachonis a muscle,” explained Hecht. “You wouldn’t show up to a marathon without training; you would practice a little bit every day, and then when you show up to the marathon, you would know you would be OK. Trust in G‑d is always going to be a struggle, but we need to exercise this muscle.”

Shaar HaBitachon breaks down what it means practically to trust in G‑d and how sharpening the very trust itself can bring about the results being sought. This book is the guide to the workout, but the work itself must be done by the individual.

From Concept to Publication

In 2019 the team at Chayenu, a nonprofit organization that publishes a weekly Hebrew-English Torah study companion bringing Torah study to the masses in a user-friendly format, sat together, brainstorming new projects. Recognizing that every person has struggles which can take a deep toll, whether major crises or the toil of day-to-day life, Rabbi Yossi Pels, the executive director, mentioned Shaar HaBitachon.

That’s when Rabbi Itzick Yarmush, the content editor at Chayenu, began spending a few hours each week doing in-depth research collecting the classic rabbinic and Chassidic explanations of Shaar HaBitachon and compiling them into a comprehensive commentary.

Enter Howard Glowinsky and his wife, Claire. Passionate about sharing ancient texts in a readable, accessible way, the Glowinskys were excited to be involved in this project.

Glowinsky had previously studied an older version of Shaar HaBitachon with Yarmush, and though he found the study enlightening, felt the existing English presentation was dry and difficult to read. Knowing that Chassidic sources have a deeply practical approach with a profound awareness of the human condition, he was uplifted to see the enlightening commentary Yarmush was compiling. With the Glowinskys’ funding, a page at a time was published weekly in the back of the Chayenu study magazine and sent to thousands of readers worldwide. The feedback began to pour in.

One reader shared that the material had helped them begin to finally heal from childhood trauma. Another shared that it had made their day-to-day frustration with other people ease up. Countless others informed the team that they had not missed a single issue since the start of the serialization because it meant that much.

The project was beginning to change lives, and it quickly dawned on the team at Chayenu how large this project was becoming. Teaming up with Kehot Publication Society, they began working to turn the weekly installments into one cohesive work, with Kehot adding a crisp, clear new English translation by Rabbi Yisroel Dovid Klein.

Rabbeinu Bachya counsels that G‑d responds when one has trust, and the project itself was beginning to move in that direction. On the last day of the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute’s national retreat, Pels stepped into an elevator. Next to him stood Getzy Fellig.

For years Fellig had been studying the text of Shaar HaBitachon daily with his wife, Alisa. The couple had even been discussing the need for an updated edition of Shaar HaBitachon. Pels and Fellig’s minute together in the elevator was enough time to start a conversation that would lead to the new Fellig Edition of Shaar HaBitachon.

‘It’s Fair to Say It Changed All of Us’

With anxiety rampant worldwide, Shaar HaBitachon offers a balm—by leaning into the trust in G‑d, one can be gifted with a life of tranquility.

“If we are constantly concerned about if we have enough trust in G‑d for it to work, then we have just become slaves to the trust. The key is to truly relax into that trust, to put all our stress and worries in G‑d’s hands,” said Yarmush.

Throughout his life, Glowinsky has had times that were heavy with worry; there was always something to be nervous about, whether it was business, financial strain or the stress of raising a family. When he began studying the text and discussed the topics he learned with his study partner, Yarmush, he started to notice a real shift in the way he experienced his world.

During production, the book release kept getting delayed for various reasons. Deadlines had to be revised, plans adjusted or completely changed. The constant frustration and stress began to take a toll. But the reminder of how to handle the disappointments was sitting right in front of them. “It’s fair to say it changed all of us,” Glowinsky said.

Even before publication, the project began to take on a life of its own. A mentor to the Glowinskys, Rabbi Mendel Kaplan, director of Chabad Flamingo in Thornhill, Ontario, and a prolific Chabad.org contributor, had been hearing about the project from a distance. Then, as Covid-19 hit and the surprise spring of 2020 turned into the tumultuous and uncertain summer of 2020, a member of his Toronto community urged Kaplan to begin teaching classes that focused on the topic of faith and trust in G‑d. Faith was hard to come by, and the need for an anchor was deepening.

So Kaplan began teaching weekly 15-minute sessions from Shaar HaBitachon. As interest in the classes grew, Kaplan decided he would begin teaching those classes online for the worldwide community. The videos would be published and shared on Gateoftrust.org, a website that gained momentum as this new edition became more and more widespread, and are also available for viewing on Chabad.org .

But as Kaplan prepared his early videos, he realized he had underestimated the depth of what he was teaching. He began to spend three to four hours a day doing deep dive research into every quote and idea discussed. His daily classes have since developed into hour-and-a-half-long sessions that leave no word or concept unexamined and explained.

“I’m experiencing life-changing learning myself,” Kaplan shares, a path of discovery he is happily sharing with his countless students in Toronto and around the world.

Other teachers featured on GateofTrust.org include such prolific educators as Rabbi Shais Taub, who produced a series of 42 lectures on the book, and Rabbi Yosef Y. Jacobson. There are also hundreds of essays and other resources on the website, many drawn from Chabad.org, including those written by Rabbi Tzvi Freeman and Chana Weisberg, which expound upon the many facets of this unique read.

When the book was finally nearing publication, Rabbi Menachem Katz, the director of military and prison outreach at the Aleph Institute reached out to Pels and arranged for 4,000 copies to be shipped to Jewish inmates and U.S service members across the country. Katz says that the recipients were deeply moved with some sharing how it eased the pain of being in a stressful and anxiety-filled environment.

“An inmate is often imprisoned within a prison because they are in a constant state of stress and anxiety about their fate,” said Katz, “when you let go, and let G‑d, you’re halfway out of prison.”

Shaar HaBitachon’s first print sold out within six weeks, and a second print was immediately ordered.

“This isn’t just a good read for those who are interested in Torah study,” observes Yarmush. “It’s a necessary read for anyone who is looking to bring more peace and tranquility into their lives.”

Gate of Trust can be purchased online at Gateoftrust.org and Kehot Publication Society , and at Jewish bookstores.