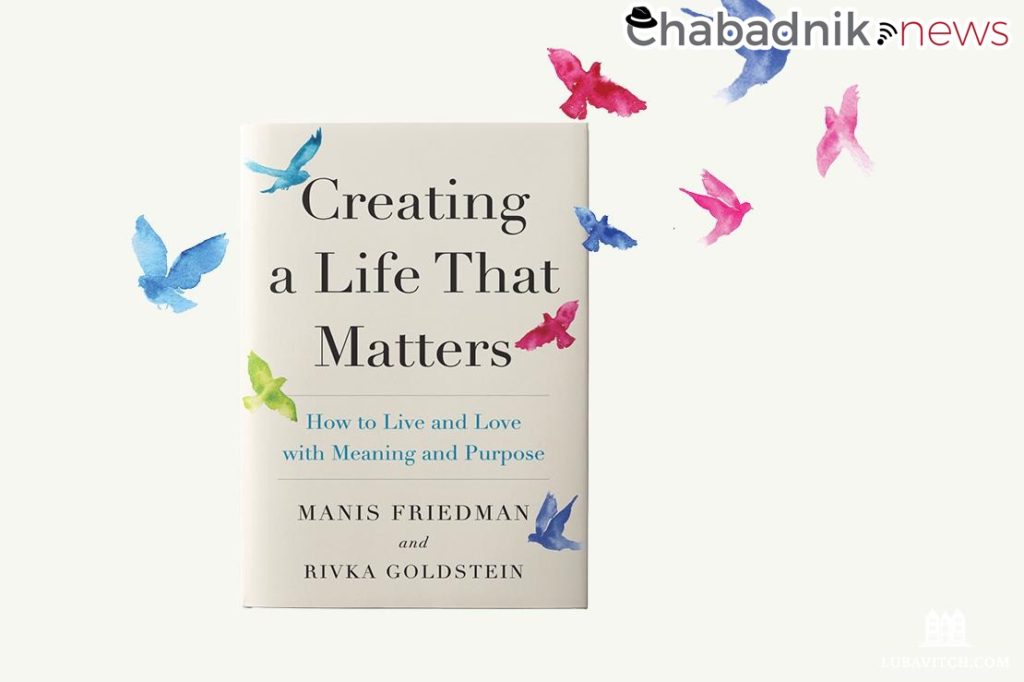

Creating a Life That Matters: How to Live and Love with Meaning and Purpose

Manis Friedman & Rivkah Goldstein

It’s Good To Know Publishing

To paraphrase the punchline of an old Chasidic story: the difference between a window and a mirror is a thin coat of silver. The affluence of our society affords us opportunities that our grandparents would not have dreamed of. But while the opportunities are vast, our view is narrow. Indeed, our prosperity seems often to result in us seeing nothing but ourselves.

We live in an age that is more concerned with self-help, self-development, self-empowerment, self-actualization, and self-care than any other age in history, but we are no happier.

Despite the wealth of opportunity and relative ease of our society, the freedom from war, hunger, and displacement, the free availability of teachers, texts, and other avenues of self-education — the many things we take for granted — too often, our experience is intensely dystopic. There is hunger, malaise, and unrest. We seek more.

Set against this backdrop, in Creating a Life That Matters: How to Live and Love with Meaning and Purpose, co-authors Rabbi Manis Friedman and Rivka Goldstein explore the search for meaning in our contemporary society, drawing on the teachings of Kabbalah and Chasidut.

Friedman begins with an exploration of the journey of the soul, which serves as a paradigm for the pursuit of meaning in life and love. After all, explains Friedman, the soul is the part of ourselves that does not simply exist — taking up space and resources — but that is eternal and transcendent, truly alive and in consonance with its mission and its G-dly source.

Friedman’s insights are most useful if they are read as suggestive, a way of playing with new ideas and paradigms and seeing how they might expand our thinking.

The beginning of the soul’s journey is G-d’s decision that He desires a world, a relationship with something “outside Himself.” Friedman brings this point to demonstrate that, contrary to popular belief today, a relationship does not begin with love. It begins with a choice.

G-d’s first act is not love, but the decision — perhaps we may call it the need — to create. And only then, as reflected in the Kabbalistic Sefirot, does he create love on the first day of creation, as a tool and support for the success of His creation. When it becomes clear that love alone is not sufficient to sustain His relationship with the creation, He adds severity, compassion, and loyalty to the mix. The days of creation mirror these Divine attributes, unfolding in creation as emotional stances unfold in a relationship. But it begins with a commitment freely chosen.

The first section of the book also explores the distinction between “facts” and “truth.” For example, a person is in a car accident and nearly dies. That is a fact. But the person deserves to live his life to the fullest. That is “truth.” As Friedman notes, when facts surrender to truth, we call it a miracle. The belief in Moshiach, or the Redemption, he explains, is the conviction that one day, there will be no division between facts and truth. In the meantime, we live in a world of facts, not truth, with all the pain and injustice that entails. Yet this is a necessary state in an imperfect world. For if we saw only truth and did not experience “facts,” we would not be motivated to improve and change the world, and that is our purpose.

In the second and third sections of the book, Friedman applies these general concepts to marriage and parenting. It is easy to see how these ideas challenge contemporary mores of dating and marriage. Marriage, Friedman argues, is not primarily about finding love, but about making a commitment. Love is a gift given freely to spouses, children, and parents, rather than the prerequisite for a caring and constant relationship. We need to “look” at each other less and “listen” more — to be more concerned with our inner connection to a spouse and less concerned with externals. In a culture obsessed with maximizing pleasure and boosting the “wow” factor of our relationships and love, this is a fresh perspective that allows us to think differently about what it means to live with and maintain our commitment to imperfect people.

The third section of the book is the most loosely structured, dealing with parenting issues and questions. It reiterates many of the earlier themes and emphasizes the role of morality in parenting. Perhaps the most significant insight here is its exhortation to parents to have the courage to take on the role of parent (rather than peer or best friend) and to have confidence in that role.

To be sure, some of the discussion feels at times like an oversimplification or a semantic game (especially when condensed into a summary sentence). Other bits of advice are too general to be usefully applied in all cases. Friedman’s insights are most useful if they are read as suggestive, a way of playing with new ideas and paradigms and seeing how they might expand our thinking. As with many discussions of Kabbalah and Chasidut, there is danger and frustration in reading them too concretely. Friedman’s style is provocative and playful, and it is best received in that vein.

Those who have heard Rabbi Friedman speak before can expect this will be another engaging presentation of the foundational ideas of Kabbalah and Chasidut. What is more, his co-author, Rivka Goldstein, has done a masterful job at moving beyond the abstract and the provocative, making it more grounded and practical. For those to whom the work of Rabbi Friedman is new, prepare to be surprised and delighted — and at times incredulous — as you rethink some of the truths that you have taken for granted.