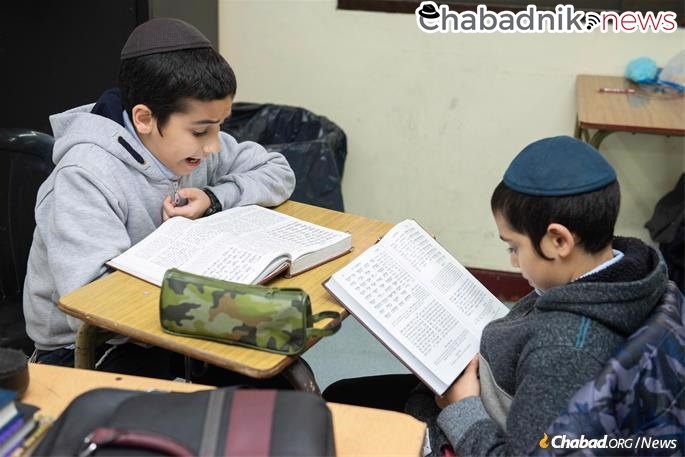

Community school keeps up with explosive growth in Torah-based education

Amid the economic woes and rising inflation that plague Argentina and its 250,000-strong Jewish community, Chabad’s school system, Oholey Chinuch, is experiencing explosive growth. With parents attracted by quality education and traditional values, each year the need for additional space increases.

“The classes are jammed,” says Rabbi Tzvi Grunblatt, regional director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Argentina. “We cannot add to our existing space.”

The current trajectory means that Oholey Chinuch needs to add many new classrooms over the coming years.

To accommodate that growth, Chabad broke ground in late 2020 on a $25 million campus spanning 247,570 square feet. Construction began in January 2021. The first phase is set to be completed in March 2023, when the children will begin learning at the expansive new campus. All in all, the educational hub will house 1,900 students in three buildings. A 70,000-square-foot building will accommodate the boy’s elementary school, along with a gym, a flexible event room, cafeteria, playgrounds and courtyards. The eight divisible classrooms will be complemented by a library and capped by a rooftop garden.

The adjacent 170,000-square-foot building will house the preschool and girl’s Bnot Israel elementary and high schools, with the recreational spaces shared between the divisions. Another 23,700-square-foot wing will serve as the campus’ administrative center.

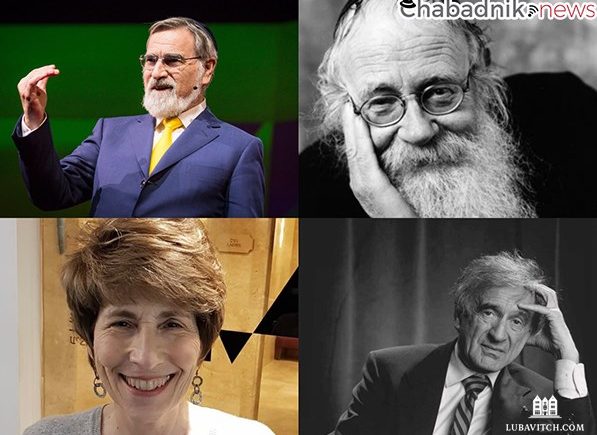

The Buenos Aires educational hub was founded in 1974 by Rabbi Berel Baumgarten, the pioneering Chabad-Lubavitch emissary sent by the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—to Argentina, who worked tirelessly to reinvigorate the community from 1955 until his untimely passing in 1978. When the community requested that Rabbi Tzvi Grunblatt—an Argentine native who had gone to study at Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters in Brooklyn, N.Y.—return to Argentina, the Rebbe agreed. Not long after, Grunblatt celebrated his marriage to Shterna Kazarnovsky, and barely a week afterward, the couple landed in Buenos Aires.

As Chabad in Argentina grew, so did the school. It began with three students, and “nobody dreamed it would reach these heights,” Grunblatt tells Chabad.org. “The school has, thank G‑d, a very good name,” says Grunblatt, noting that the reputation, coupled with other factors, led to its remarkable growth. That came even as the community began to shrink in the wake of political instability and exacerbated by the two mass terrorist attacks targeting Jews have never been solved—one at the Israeli embassy in 1992, which killed 29 people; and the other at the AMIA (Argentine Jewish Mutual Aid Society) building in 1994, which killed 85 people and injured more than 300.

“The Chabad community has natural growth; families are having children,” says Grunblatt, adding that as a result of Chabad’s activities, parents from outside the immediate Chabad community are increasingly choosing to give their children are rigorous Jewish education and see Oholey Chinuch as the school of choice.

An Urban Oasis for Kids in Buenos Aires

In addition to the increased classroom space, Grunblatt points to another critical solution the new campus will provide. Buenos Aires, a densely populated city far outpacing New York City in population density, has little outdoor space for children to play and explore. “The children live in small apartments and spend most of their day in school,” says Grunblatt, so “the school has to provide breathing space for them to thrive.” The new campus will be filled with natural light and outdoor space, giving the children the natural environment they crave.

Despite the economic woes that plague Argentina, Chabad saw a groundswell of support from the local community and Argentine expats around the world. Though it’s been 25 years since he lived in Argentina, Eduardo Azar and his wife, Leticia, Argentineans living in Miami, still feel a strong bond to their native country. “Rabbi Grunblatt is my hero; the transformation he accomplished in Argentina is exactly what the Rebbe envisioned,” says Eduardo. “Jewish life there is off the charts. I can see the Rebbe smiling.”

Azar credits his philanthropy to an encounter he had with the Rebbe in 1985, which he says changed his life. “The Rebbe taught me to give tzedakah, to give back to society.” He feels strongly about the importance of Jewish education, explaining that “if we don’t invest in education, we’ll be dealing with the consequences later. I support other educational institutions as well, but Chabad made the transformation; everyone else will follow their lead. The Rebbe said to invest in education; we need to start out on the right foot.”

And the investment pays off: “The teachers and leaders of the community come out of this school,” Grunblatt stresses. “They power Argentina and all of South America. It’s not just a school for children, but a community treasure.”