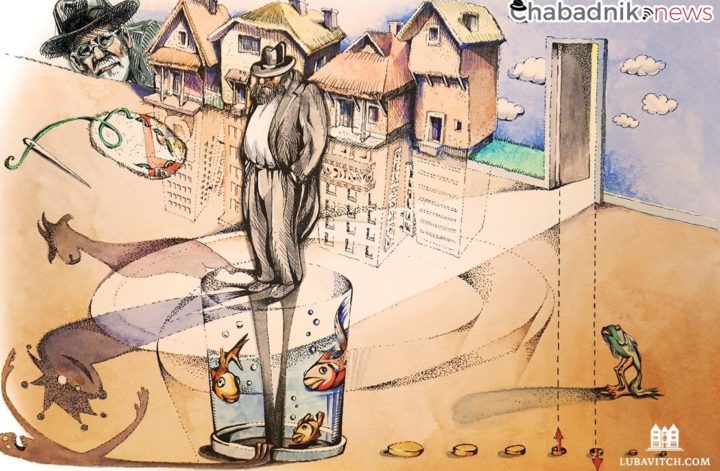

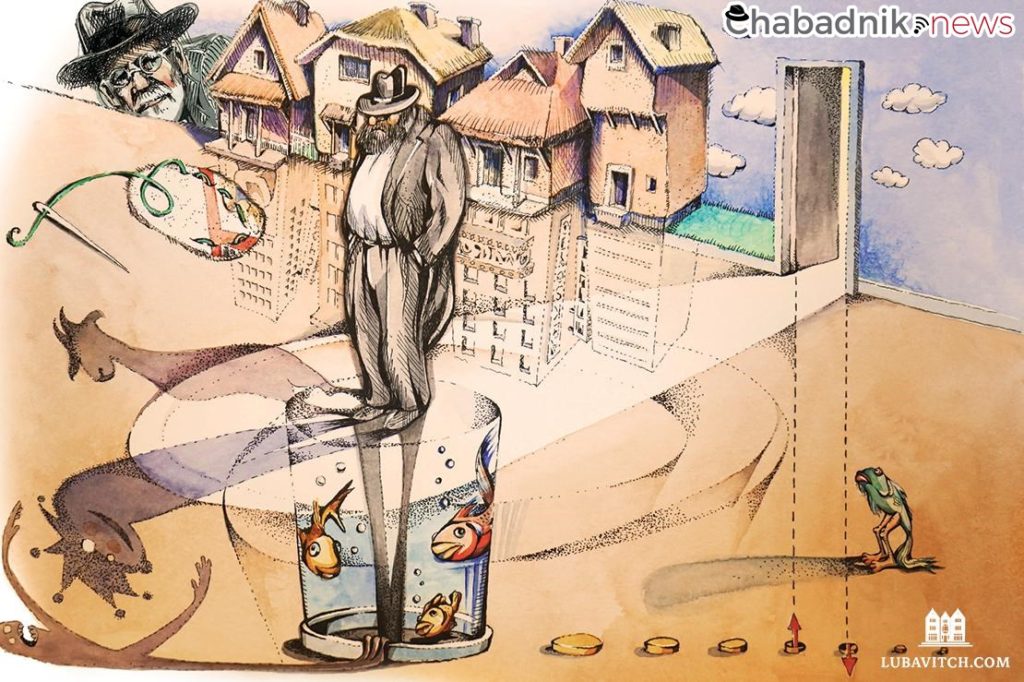

How humor can make room for a deeper truth otherwise concealed by the apparitions of this world

In his 1905 philosophical analysis of humor, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Sigmund Freud cites a classic Jewish joke: “Two Jews met in a railway carriage at a station in Galicia. ‘Where are you going?’ asked one. ‘To Cracow,’ was the answer. ‘What a liar you are!’ broke out the other. ‘If you say you’re going to Cracow, you want me to believe you’re going to Lemberg. But I know that in fact you’re going to Cracow. So why are you lying to me?’”

On the surface, the joke is a self-deprecating jab at the Jewish tendency to overthink things. But on a deeper level (and for Freud of course there is always a deeper level) the joke comments on the difficulty of discerning truth. He asks, “is it the truth if we describe things as they are without troubling to consider how our hearer will understand what we say?” Freud proposes that jokes like the one above “attack not a person or an institution but the certainty of our knowledge itself.” He is struck by how many jokes of this nature are Jewish ones.

Discussions of Jewish humor commonly point to years of oppression and living as a minority, at odds with a majority culture, as a driving force behind the Jewish comedic imagination. Comedy has been a way to cope with powerlessness, as in the world-weary humor of Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, who asks G-d: “I know, I know, we are Your chosen people, but once in a while can’t You choose someone else?” Another way to look at Jewish humor is to find in it absurd examples of Jewish intellectualism or neuroses, the over-examined life taken too far. Think of the Jewish mother jokes and the Jewish doctor jokes. The waiter who greets a group of five Jewish women sitting together at a table and says, “Ladies, is anything ok?”

Beyond these signature tropes in Jewish humor (which, while perhaps recognizably Jewish, are not overtly religious in nature), there may be a spiritual quality to the act of jokemaking itself, and particularly Jewish jokemaking, that transcends the specific subject matter of any one gag.

The Talmud notes the important role of laughter in the religious psyche. One story recorded in Taanit 22a describes a conversation between the sage Rav Beroka Choza’ah and Elijah the Prophet. Rav Beroka asks Elijah which people in the marketplace will merit a place in the World to Come. Rather than point to a traditional righteous person, Elijah highlights several people who would not obviously pass for righteous: a jailkeeper dressed in non-Jewish clothing and a pair of jesters (“badchanim”). Elijah reveals that the jailkeeper’s outward appearance hides a hidden holy agenda that one would never have guessed. The jokesters, too, are more righteous than they seem, Elijah reveals. But while the jailkeeper’s saintliness is hidden, the jokesters’ virtue hides in plain sight. The very reason one might think they are not particularly saintly — the fact that they make their living lightening the mood and distracting people from their sorrows — is precisely the source of their greatness.

The idea that comedy carries its own kind of holiness seems to underlie the Kabbalistic/Chasidic concept of “shtut d’kedusha” (“holy folly”). That is, unconventional or crazy behavior that can serve to bring one closer to G-d. This manifests in dancing with reckless abandon at a wedding, levity at a farbrengen (a Chasidic gathering), or the elevation of seemingly foolish figures who, in their naivete or lack of concern for outward appearances, reveal hidden truths about our world. Sources for this notion are found in the biblical story of David dancing before the Ark of the Covenant (Samuel II, Ch 6) and the Talmudic reaction to Rabbi Shmuel bar Rabbi Yitzhak’s outlandish wedding dances (Ketubot 17a). This mystical notion acknowledges that behavior which seems less than serious at first glance need not imply irreverence. In fact, the non-seriousness has a unique role to play in the service of G-d.

Rabbi Mendel Futerfas, a legendary Lubavitch Chasid and crusader for Soviet Jewry who spent many years imprisoned in Russian labor camps, was well-known for his farbrengens and colorful anecdotes. For Reb Mendel, comedy was not just a pastime — it was part of a life philosophy. He used to say that humor is crucial in order for a person “not to fool himself about himself.”

Rabbi Naftali Loewenthal, a London-based scholar of Jewish mysticism, spoke to me about Futerfas and his belief that humor enables a person to look at the world with perspective. Lowenthal explained that comedic irony fosters this kind of perspective, helping a person balance the forces of the divine soul pushing for good and the temptations of the world. Humor “takes the air out of the urges within a person,” and in doing so clears a space for them to connect with something that transcends the narrow self.

Wonderful examples of this sort of humor can be found in stories told about Rabbi Shmuel Munkis, a great scholar and close disciple of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad. Although Rabbi Munkis was best known as a pious Chasid who tolerated no falsehoods, he was also a serial prankster.

In one tale, presented in Rabbi Shalom DovBer Avtzon’s book Reb Shmuel Munkis, Rabbi Shmuel comes across a rather self-important man who is traveling to see Rabbi Schneur Zalman, also known as the Alter Rebbe. The man tells Rabbi Shmuel that he is incredibly learned in Kabbalah and wants to test the famous Alter Rebbe to see if he is indeed as brilliant as people claim. Rabbi Shmuel puts on an impressed face and explains that he too has a difficult question about the Kabbalah, and would he, the traveler, be willing to pass his question along to the Alter Rebbe. Rabbi Shmuel’s question goes as follows: “It is written in one of the books of Kabbalah: ‘First it was scattered, then it became connected. Then it came to the level of a great circle. The level of the three lines was then applied to it and it became the aspect of a triangle with the point in the middle. And through the combination of the foundation of water with the foundation of fire, it was finished, and it became good.’ So it is written, but I cannot discern its true meaning.”

The traveler concentrates greatly but can not make sense of Rabbi Shmuel’s passage, so he agrees to share it with the Alter Rebbe and report back with the answer. When the traveler finally arrives at the home of the Alter Rebbe, he introduces himself in grand terms and presents this fine question. The Alter Rebbe looks at him, smiles, and says, “The answer is a krepal.” Namely, the singular form of kreplach, a traditional triagonal meat-stuffed pastry.

Structurally, this joke, which in Rabbi Avtzon’s telling goes on a bit longer, could fit right into any Jewish humor anthology. Yet one detects something more than a clever punchline here. Rabbi Shmuel is a Chasid, and Kabbalistic concepts are not something one ordinarily pokes fun at, even in order to provide an essential service of ego deflation. Yet the ironic detachment that allows Reb Shmuel to make this kind of joke (and the Alter Rebbe to appreciate it) indicates that their tradition is a healthy living organism. They live within it fully and comfortably, so they don’t need to take it entirely seriously all of the time. The message to the Kabbalah expert is not only that he is not as knowledgeable as he thinks he is, but also that in turning his mystical knowledge into bragging rights, he actually ossifies it.

At another juncture, the Alter Rebbe is charged for a crime he did not commit and is trying to evade the Czarist authorities. Rabbi Shmuel encourages him to submit to arrest. “If you are a Rebbe,” Rabbi Shmuel tells the Alter Rebbe, “you have nothing to fear by being arrested. If not, what right did you have to deprive thousands of Chasidim from enjoying the pleasures of this world?!” (Avtzon, 35). The anecdote is telling of Reb Shmuel’s comedic tendencies — both in their unexpected timing and their nuance. Is this a moment of deep faith or one of humor?

In her book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor, Harvard University Professor Ruth Wisse notes that, “ideologues do not welcome levity. Joking flourishes among those who sustain contrarieties, tolerate suspense, and perhaps even relish insecurity.” What we see in the jokes of Shmuel Munkis are paradoxes that carve out space for a truth that lies beyond ideology. In the context of his humor, upending certainty is not engaging in nihilism. Rather, it makes room for a deeper and broader truth that may be concealed by the apparitions of this world.

In a 1953 discourse, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson discusses a well-known statement by one of the rabbis in the Talmud: Raba began each of his Torah lectures with a “milta d’bidichuta”— a humorous remark. In response, the Sages would laugh, and then Raba would sit in reverence and begin his lesson. The Rebbe explains, “the jest is what opens the heart and mind of the student, making him a vessel fit to receive the inner dimension (hashpa’ah penimit) of his teacher’s wisdom.” He quotes the second Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Mitteler Rebbe, as saying that “laughter is rooted in the soul’s potential for simple, uncompounded pleasure.” One can be suspicious of laughter for the very same reason. It involves losing one’s footing, forgetting one’s self, a loss of reason or control. But that very loss of control connects us to the deepest parts of our souls and opens up the possibility of transformation. The Rebbe writes, “When a person laughs, he is uncontrolled; he loses consciousness of his self. And by doing so, he taps into the essence of his soul that is also unbounded.”

The following joke is cited by Joseph Telushkin in his anthology Jewish Humor as having been circulated among British Jews in the 1950s, when the British empire was winding down:

A Chasidic Jew leaves his small town in Poland and comes to London. He immediately discards his religious garb and habits, and seeks to become an Englishman. He goes to law school and marries into a prestigious, assimilated Jewish family. One day, he gets a telegram, announcing that his elderly father is coming to visit. The man is thrown into a panic. He goes down to the port to meet his father and tells him: “Papa, if you show up at my house with your long coat, your head-covering, your beard, it will destroy me here. You must follow everything I ask you to do.” The father agrees. The son takes his father to the finest tailor in London and buys him a beautiful suit. Still, the old man looks too Jewish. So his son takes him to a barber. The beard is quickly shaved off, and the old father is starting to look more and more like a British gentleman. But there’s still one problem: the peyot — the sideburns around the old man’s ears. “I’m sorry, Papa,” says the son. “We have to cut them off.” The old man says nothing. The barber cuts off one peya. There’s no reaction from the old man. But when the barber starts to cut off the second peya, tears start streaming down the old man’s face. “Why are you crying, Papa?” the son asks. “I’m crying because we lost India.”

A joke offers a space in which we can recognize our delusions — like that of a Chasid who will never be a British gentleman — for what they are, and begin perhaps to entertain something new. It can open up a paradoxical space where a certain awareness beyond the joke, and even the world of the jokesters, can be apprehended. Jewish humor is not only a byproduct of our neuroses and persecution, but also an avenue for us to realize some of our loftiest spiritual aspirations.

Source: https://www.lubavitch.com/holy-folly-using-humor-to-reach-for-g-d/