Leonard Holtz found an archive of letters in a shoebox. Then he and his wife gave it to the Chabad Library

In July of 1941, a worried Rabbi Shimon Leib Greenberg of Chicago sent a letter to a Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied France who had just arrived in New York. The Warsaw-born Greenberg had lived with his wife and stepson in Paris before moving to the United States in 1939, intending to send for his family when he could. In September of 1939 World War II broke out, and by early summer of 1940 the Germans had captured Paris and communication was severed. Did the recent arrival have any word of Greenberg’s loved ones?

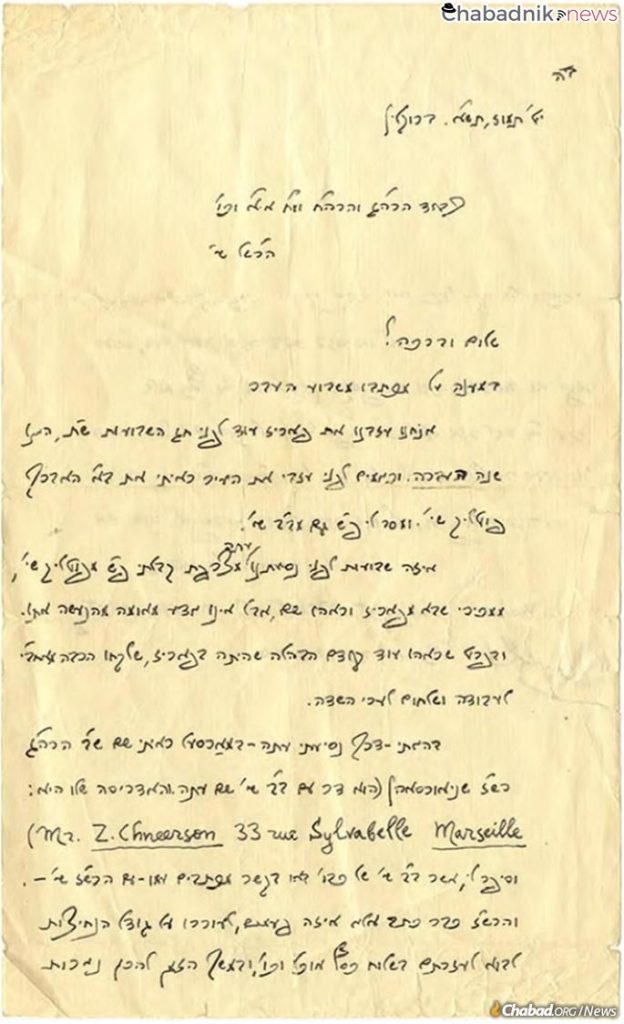

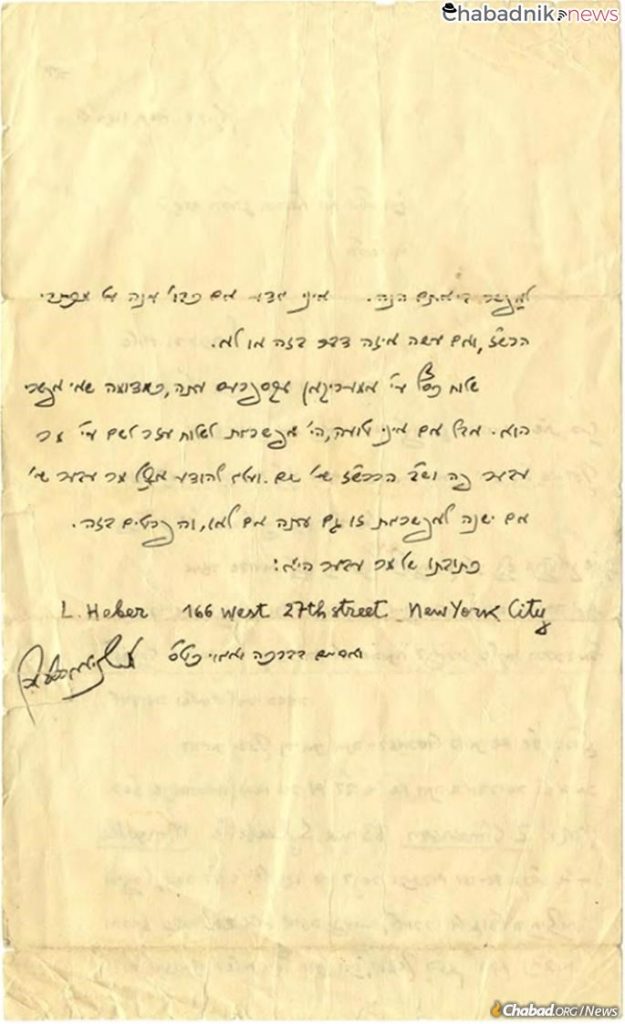

On Monday, July 14, 1941 (19 Tammuz, 5701), the refugee responded in a hand-written letter. He and his wife, he wrote in Hebrew, had left Paris just days before the Nazis’ arrival on June 14, 1940. Before that, he had seen Greenberg’s stepson, a young man named Yaakov Potlik. But that was then. “A few weeks before our recent trip from France I received regards from Potlik from acquaintances who had come [to Marseille] from Paris and had seen him there,” he wrote. “But they don’t know what the current situation is, in particular since they last saw him before the current chaos in Paris, when [the Nazis] took many of our brethren Jews and sent them to work” in labor camps.

The author of the letter helpfully writes out an address for Rabbi Zalman Schneerson, a Jewish activist aiding refugees in Marseille, and suggests that Greenberg maintain contact with him in order to send food, money and immigration documents to his wife and stepson.

He continues, “Currently, it seems to be impossible to send money [to occupied France] through American Express. However, there might be a way to send money through [another recently arrived immigrant] Mr. [Leibish] Heber, and it is best to verify that with him directly.”

The new refugee was Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, still nine years away from assuming his father-in-law’s position as Rebbe of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. The Rebbe had arrived in New York on the S.S. Serpa Pinto three weeks earlier together with his wife, the Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka.

Greenberg was an eminent Chabad Chassid who had studied at the yeshivah in the White Russian village of Lubavitch, and the Rebbe had known him in Poland and then during their years living in Paris. In response to his request for information, the Rebbe wrote Greenberg his detailed letter and dispatched it to Chicago, where Greenberg was living at the time.

The letter was among Greenberg’s possessions when he relocated to Hartford, Conn., in 1947, but remained entirely unknown to the world. Last Sunday, on June 13, 2021, Leonard Holtz discovered it in a shoebox in his Hartford-area basement, nearly 80 years to the day of its writing. The letter is a unique historical document because it is one of only two known surviving letters written by the Rebbe in the Jewish calendar year 5701, or October 1940 to September 1941. In fact, the next known letter is dated May of 1942.

More, this newly discovered letter sheds light on the Rebbe’s efforts to help his fellow Jews stranded in the Holocaust that would consume European Jewry. The curious fact is that despite the Rebbe’s voluminous output (his published letters alone fill 33 volumes), almost none of his early war-time correspondence have surfaced—though he certainly wrote correspondence during this period. That means there are surely many more out there.

From the moment of the letter’s providential discovery the team of scholars at Vaad HanachosB’Lahak(Lahak), led by Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook, worked for days straight to bring it to print, adding copious background and sources in the footnotes. As he went through last-minute proofreading, Brook commented that there are several layers of meaning in the letter.

“It is the first time that we see the Rebbe himself speaking of his escape from Paris to Vichy France and then on to America,” he explains. “We knew this information from other testimonies, but here the Rebbe describes it himself. It’s a major revelation.”

The letter was published at the conclusion of Shabbat by the Kehot Publication Society in a pamphlet together with a Chassidic discourse delivered by the Rebbe in 1974. It also includes a second recently discovered letter—this one from the summer of 1942—addressed to a Chabad Chassid in a refugee camp in Jamaica, to whom the Rebbe notes he is sending seforim (books)and prayer books for the Jewish refugees in the camp.

But the 1941 Holocaust-era letter almost didn’t reach the light of day. That is, until Laura Zimmerman asked her husband, Leonard Holtz, the director of the Hebrew Funeral Association in Hartford, to perhaps spend some time clearing out their basement of the many old books and papers that had piled up there over the years.

The day was Sunday, June 13, 2021, or the 3rd of Tammuz on the Jewish calendar, which was also the 27th anniversary of the Rebbe’s passing. But the story doesn’t end there.

“I thought to myself, ‘Is this real?’ ” an emotional Holtz tells me by phone about the hours after his discovery, and the otherworldly events that followed. “Could this really be?”

And then: “Why did the Rebbe pick me?”

Hartford Roots

Leonard Holtz is a collector by nature. Over the years, he has built up a large collection of Civil War materials and documents. He reveres old things, particularly Jewish ones: the musky smell of old books; the stamps denoting they came from Vilna, Kovna or Warsaw; the fading, swirling ink of handwritten Yiddish letters. To him, these aren’t just items but pieces of history, a paper trail attesting to the lives of individuals who inhabited a world that no longer exists.

This can be a difficult trait, particularly for someone like Holtz, who directs a Jewish funeral home established in Hartford in 1898. From time to time, people ask Holtz to bury the sacred Jewish books and belongings—otherwise known as shaimos or geniza—of their loved one. But as a collector, Holtz finds it difficult to just discard these items, even if it’s being done in accordance with Jewish law, which often requires their burial.

“It’s hard to bury these old seforim, so I have the habit of holding on to some of them and asking around if anyone wants these things,” he explains.

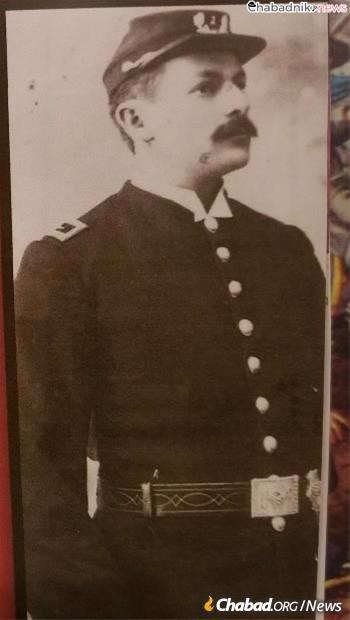

The Holtz family’s roots go way back in Hartford, where Leonard’s German-Jewish great-grandfather settled in 1865 after serving in the Union Army during the Civil War. The veteran was among the founders of Ados Israel, an Orthodox synagogue in Hartford of which Holtz’s father, the later Herman Holtz, was still president when it closed in the mid-1980s, after most of the city’s Jews had relocated to other parts of the city.

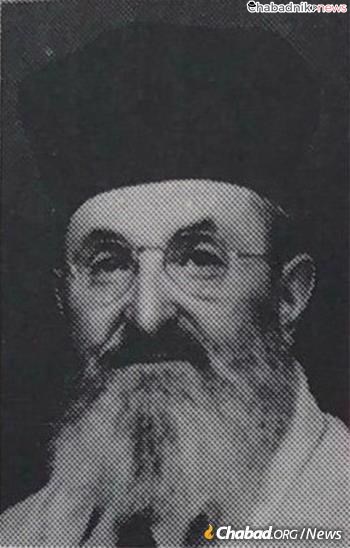

How Rabbi Shimon Greenberg made it to Hartford is another story. Born in Poland around 1893, he traveled to White Russia and studied at the famed Lubavitcher yeshivah in Lubavitch. Greenberg was a prolific chazzan, and a number of his original compositions are considered Chassidic classics—among them a tune set to the words Al Achasfrom the Haggadah. Back in Poland, he married a young widowed mother by the name of Chana Potlik (nee Hurewitz.) In 1932, the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—sent Greenberg to Paris as his emissary, where he raised funds for the yeshivah, worked as a shochet and ritual scribe, and taught Torah. Finding it difficult to support his family, he set out for America in 1939, where he first settled in Chicago. It was from there that he reached out to the Rebbe; tragically, as Lahak’s research shows, Chana Greenberg and her son Yaakov Potlik were deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

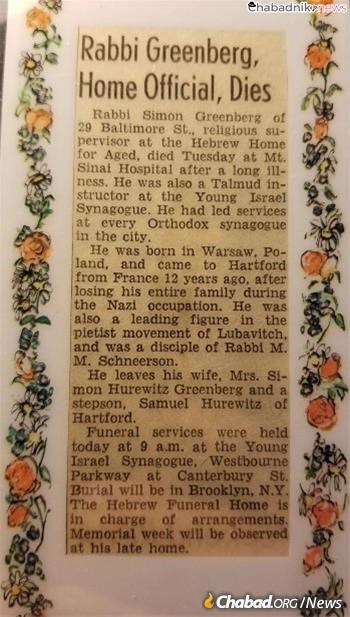

In 1947, Greenberg moved to Hartford and married a second time. His second wife was likewise a widowed mother, whose name, remarkably, was also Chana Hurewitz—though not seemingly related to his first wife. There, Greenberg worked as a rabbi at the Hebrew Home for the Aged, taught Torah at the local Young Israel synagogue and was a renowned chazzan in the city before passing away in 1959. “He was also a leading figure in the pietist movement of Lubavitch,” his death notice reads, “and was a disciple of Rabbi M.M. Schneerson.”

The now-twice widowed Mrs. Hurewitz Greenberg turned to Herman Holtz, funeral director of the Hebrew Funeral Association in Hartford to conduct the funeral. The elderly Chassid’s services were held at Young Israel of Hartford, but instead of being buried in Connecticut, he was transported to New York and interred at Old Montefiore Cemetery in Queens, N.Y., just a few rows away from the Ohel of the Sixth Rebbe, which, since 1994, is the site of the Rebbe’s resting place as well.

In 2015, Greenberg’s stepson from his second marriage, Samuel Meyer Hurewitz, passed away at age 80 in Hartford. This time it was Leonard Holtz who conducted the funeral. At the time, he also received a few boxes of shaimos that had once belonged to Rabbi Shimon Greenberg, including an old, uncovered shoebox, which he placed in his basement intending to one day bury with other old books.

The Shoebox

While Leonard is a collector, his wife, Laura Zimmerman, is not. Between Leonard’s Civil War collection and the numerous boxes of old Jewish books and Judaica in their Hartford-area basement, it was getting crowded. June 13, 2021, was a Sunday—a perfect day to clean things out.

The year of Covid-19 was a difficult one for everyone, but was particularly hard on Leonard, who spent much of 2020 burying victims of the virus and fearing he could be exposed at any time in the course of his work. Sorting through the clutter in his basement proved to be a cathartic experience. When he started the day, he noticed a large synagogue furnishing with Hebrew words emblazoned on top: “Know Before Whom You Stand,” it read.

Towards the end of the day, at about 10 p.m., he finally reached the shoebox, or what he calls The Shoebox. With every intention of burying it all the next day, he began sifting through the box’s contents.

“Inside were letters, many of them all compressed, and suddenly I notice this letterhead that says ‘Rabbi Schneerson, 770 Eastern Parkway,’” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe what I was pulling out of there.” Most were typed correspondences on the Rebbe’s letterhead with the Rebbe’s signature. But one was all handwritten, only the signature matching the others.

At the time, Holtz didn’t recall it was the Rebbe’s yahrtzeit nor did he know what to make of his curious find, so he posted a few pictures on a Jewish genealogical Facebook page, including a photo of the Rebbe’s 1941 letter. Within 20 minutes he began receiving Facebook messages and friend requests asking for more information. Fortunately, one of those who saw it and reached out to Holtz was Brooklyn-based Rabbi Avraham Berkowitz, who immediately recognized the letter’s historic importance and the excitement its publication would garner.

“When I saw it I was stunned,” Berkowitz says. “We knew of almost no surviving letters for the entire 1941, and out of the blue, on 3 Tammuz, someone posts a letter written by the Rebbe three weeks after his arrival? And it’s him trying to help someone locate family members in Europe? I couldn’t sleep the entire night.”

Beyond the obvious importance of the letter’s contents, Berkowitz also strongly believed that the most fitting home for such a document was just a couple hundred feet away from where it was written 80 years ago—the Central Library of Agudas ChassideiChabad at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn.

‘Something Powerful Is Going On’

Berkowitz and Holtz connected first by Facebook messenger, and then by phone, speaking for an hour early Monday morning. Inundated with messages, Holtz took his Facebook post down. On Wednesday Berkowitz, his 17-year-old son Menachem, and his brother—Rabbi Yirmi Berkowitz of the Kehot Publication Society, representing the Chabad Library as well—drove from Brooklyn to Hartford to see the letters in person. There was the Rebbe’s handwritten letter, but others as well, including letters to Greenberg from the Sixth Rebbe. By then, Holtz had placed the items in protective plastic sleeves and laid them out on his broad kitchen table.

From the beginning, the experience for Holtz was like “stepping into a moment in my life when something very, very powerful is going on,” he says. “I realized I was dealing with something very special.” If it was only the happenstance of the date, that would have been enough. But there would be more.

The Holtzes warmly received the Berkowitzes in their home. As they looked over the letters and discussed the lives of the individuals mentioned, Rabbi Yirmi Berkowitz asked whether Holtz might have more information about Greenberg’s burial arrangements. Holtz’s father, a collector too, had retained files for funerals he did long after legally mandated, and so Holtz still had Greenberg’s full 1959 records. Then, seeking to find out more information, Holtz went into his office to pull out a copy of Jewish Cemeteries of Hartford, Connecticut, an important genealogical tool compiled in the 1990s by Edward Allen Cohen and Lewis Goldfarb with information from nearly every Jewish gravestone in the region, stretching back a century.

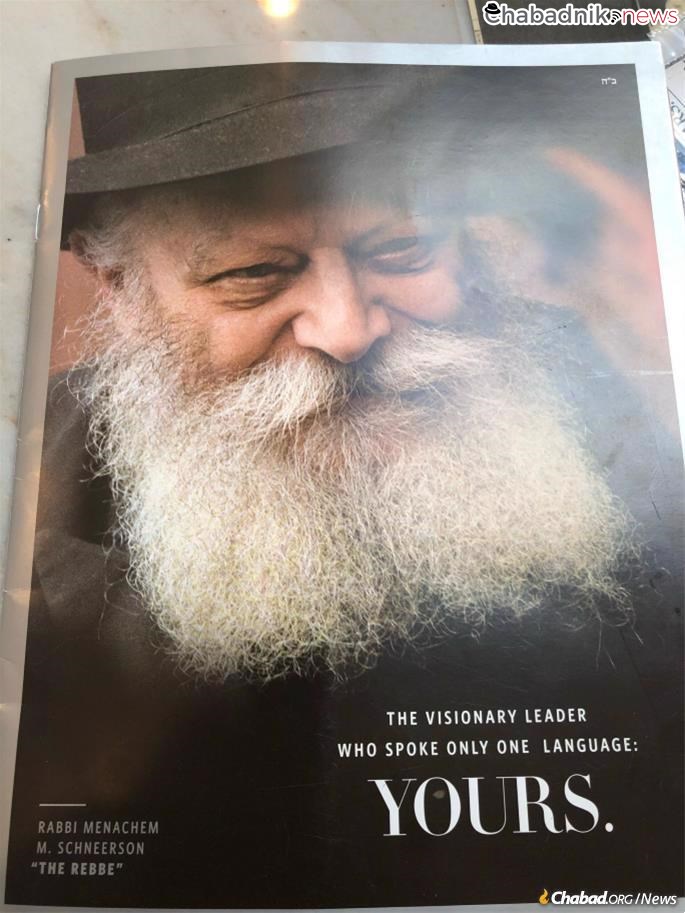

As Holtz pulled a volume out of the shelf something fell out: It was a magazine with a portrait of the Rebbe on the cover. “The visionary leader who spoke only one language,” the text on the cover reads. “Yours.”

There was an audible gasp in the room.

“It was just, ‘How is this happening?’” recounts Holtz.

The 2014 magazine had been sent to Jewish homes in the area by Rabbi Yosef Gopin, director of Chabad of Greater Hartford, but neither Holtz nor Zimmerman recalled it at all.

Then they opened the magazine. Inside was an article about Chabad’s Merkos Shlichus “Roving Rabbis” program profiling two yeshivah students who had spent their summer sharing Judaism in Alaska. One of them was Rabbi Avraham Berkowitz.

“The article was about Avraham Berkowitz and here he is in the room,” Holtz recounts. “If this didn’t happen to us, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

In the stunned minutes of silence that followed, Holtz and Zimmerman knew that the letters belonged back home at 770, gifting them to the Chabad Library then and there. On Wednesday evening, the Berkowitzes brought the newly discovered archive to Brook, who carefully scanned every letter and fragment. On Thursday morning the collection was presented to Rabbi Sholom Dovber Levine, chief librarian of the Chabad Library, where it was cataloged and added to the existing Greenberg file.

The story’s layers are multifold and intricate. There are the Holtz family’s many Hartford connections with the Greenberg and Hurewitz families, including the funeral arrangements of two patriarchs a half-century apart; Rabbi Greenberg’s martyred and forgotten family, all of a sudden coming to life; and Greenberg himself: gone for six decades, lying just feet away from the Ohel but with no one to say Kaddish for him. Then there are the boxes given for shemos that accidently went unburied, all the records saved, and all of it coming together 80 years later to the day—and on the Rebbe’s own yahrtzeit.

Holtz and Berkowitz have become friends. Together with his wife, he hopes to soon visit the Library in Crown Heights and the Rebbe’s Ohel in Queens—with a stop at the resting place of Rabbi Shimon Greenberg.

“So many things had to happen to make this happen, for the letter to go full circle and for us to meet this wonderful new family,” says Holtz. “If you didn’t have faith before, if you didn’t understand something special was happening until now—this event sends a sign.”

After all, it was the Rebbe who taught that the miraculous is in actuality a heightened sense of reality. That nothing is an accident, the world is not a discordant collection of parts but an interconnected whole, and that miracles and wonders take place all around us.

We must just open our eyes to their existence.

If you are aware of any other correspondence or archival material from the Rebbe that may be of relevance to the Chabad-Lubavitch Library, click here to help ensure that these materials are given a permanent home where they can benefit the wider public.