In honor of the 120th anniversary of the birth of the Rebbe

A lecture delivered at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. to mark the 120th birthday (1902-2022) of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson of righteous memory

In this article:

- Education Leading to Leadership

- The Divine Name – Four Stages of Education

- Singing the Rebbe’s Song

- Lamplighters – The Rebbe’s Leadership Today

- We Should All Be Leaders

Education Leading to Leadership

The Rebbe’s teachings fill hundreds of volumes, thousands of hours of audio and video recordings, and the organizations and institutions he set up are literally global. A major focus of all this material and all this effort is education that leads to leadership. The Rebbe’s goal was to educate us, and to turn each one of us into an educator and a leader, the kind of educator and leader who creates other educators and leaders.

First let us try to define what education and leadership are, in Jewish terms. Let’s start with leadership. There is a well-known story about a time in the 1840s or 1850s when the expanding network of railway lines had finally reached a small town in Poland. The chassidim were anxious to see what their Rebbe (sometimes identified as the Kotzker Rebbe) would say about the new phenomenon. He left his Study House and came with the chassidim to the newly laid rails. After a few minutes, the train appeared from the distance: an old fashioned steam engine, with a fiery boiler, belching smoke and steam, pulling a few simple carriages. ‘Nu Rebbe?’ asked the eager chassidim. What would he say?

The Rebbe looked at the train and the carriages and said ‘Ikh zeh: eyn heyser ken shleppen a sakh kelter’ – ‘I see: one hot one, the engine, can pull a lot of cold ones, the carriages.’ He had turned the new advance of modernity into a mashal, a parable about the relationship between a rebbe and the chassidim. The enthusiastic, inspired rebbe – the ‘soul on fire’, as Elie Wiesel put it –pulls and guides the others, the cold carriages.

This, however, is not exactly the Chabad perspective. Chabad is represented by a more modern kind of train in which every carriage can also function as an engine. The Rebbe’s goal was to turn everyone into an engine. As has been repeatedly said with reference to the Rebbe, good leaders create followers and great leaders create leaders.

Education is the process which turns each of us into a leader, into an engine, someone who takes responsibility for others and who seeks to make each of those others too become an engine, an educator and leader.

The Divine Name – Four Stages of Education

This talk will try to describe this process, in four basic stages. This structure is freely based on a passage in the works of the Fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe1 , whose teachings were often discussed and elaborated by the seventh Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson.

This passage presents existence itself as a communication and education process2 . This process is reflected in the Divine Name with Four Letters, the Tetragrammaton, the Name we are careful not to write, so that we do not erase it, the Name we never pronounce as it is written. Its four letters are Yud [י], and then Heh [ה], and then Vav [ו] and then another Heh [ה].

1) Yud – The Basic Point

The Yud is the smallest Hebrew letter, a dot. It means being able to narrow down what the teacher wants to communicate into a single point. There are thousands of books. What does a teacher like the Rebbe want to say for the 20th and 21st centuries?

In his first Chassidic gathering as Rebbe, formally accepting that position, on the Tenth of Shevat, 17 January 1951, he declared that there is a basic ‘statement’, what we today would call a mission statement, that defines his endeavor. His goal is: love of G‑d, love of Torah, love of one’s fellow.

The Rebbe’s talks on that occasion went on to show that each of these three are interconnected, and that all three are necessary. However, let us understand them as an educational program for the future. Love of G‑d, of Torah and of one’s fellow is a statement that includes all aspects of Jewish knowledge and of Jewish feeling, everything that the Rebbe wanted to teach us, everything he wanted us to internalize. But it focuses all of this within one small dot, the letter Yud of the Divine Name.

2) The First Heh – Broadening and Defining

Then comes the letter Heh of the Name. The Heh expands the point into a broad area of meaningful content: Jewish knowledge as needed to live a full Jewish life.

● A daily session studying one section of the weekly Torah portion with Rashi’s commentary.

- A daily session studying one section of the weekly Torah portion with Rashi’s commentary.

- Tackling the spiritual dimension of Judaism: a daily portion of Tanya, teaching both love of G‑d, love of one’s fellow – and also devotion to Torah study and the Mitzvot.

- Reading Psalms each day as arranged on a monthly cycle.

- Exploring the full gamut of Jewish law as expressed by Rabbi Moses Maimonides, the Rambam, whether three chapters a day of Mishneh Torah which means covering the entire oral law in a year, or just one chapter; or reading the briefer Book of the Commandments (following the order of Mishneh Torah).

- Studying at least one tractate of Talmud each year, joining with others so that one’s community can make a Siyum on the entire Shas on 19 Kislev.

- Regular study of practical Jewish law, in Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s Code of Law or other texts.

These are the typical study schedules promoted by the Rebbe, but of course, he would always encourage more, and more, and more…

The above list comprises Torah texts, relevant for men and for women, and also for children. But the goal of Torah is observance in practical terms and in emotional terms. This means love of G‑d, and love of one’s fellow, which both translate into action.

The Rambam compiled his Thirteen Principles of Faith to help people know which are the basic Jewish beliefs. The Rebbe sought to define basic Jewish actions, and he did this through his celebrated Ten Mivtzoim, Ten Mitzvah ‘Campaigns’:

1. Love of One’s Fellow (which translated into tangible behavior and action). Practical investment in Jewish Education.

2. Studying Torah.

3. Donning Tefilin for men and boys.

4. Affixing kosher Mezuzot on one’s doors.

5. Giving Charity.

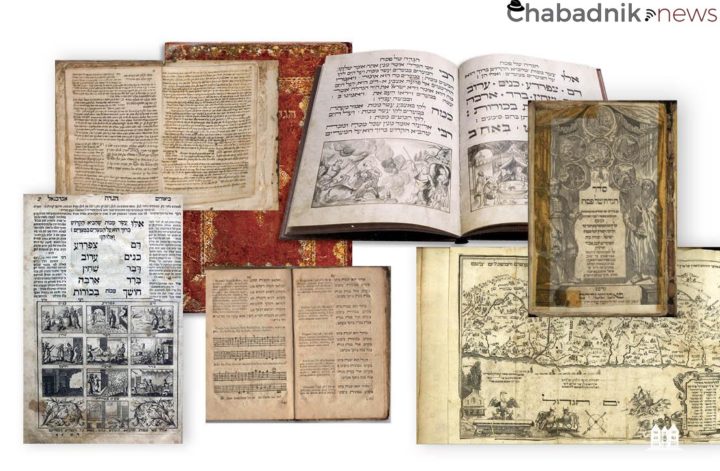

6. Acquiring Jewish Books.

7. Keeping the laws of Kashrut.

8. Lighting Shabbat Candles particularly for women and girls.

9. Adherence to the laws of Family Purity and Mikveh.

10. A further aspect which relates to action, study and feeling is the theme of yearning for Moshiach, the awareness and expectation that we are at a turning point of history.

Another aspect of the letter Heh, the expansion and elucidation of the core concepts of love of G‑d, love of Torah and love of one’s fellow, is the Rebbe’s almost unparalleled reach beyond the Jewish community with his emphasis on the Seven Noahide Laws. The Rebbe often quoted the Rambam’s statement3 that the Jews have the responsibility to communicate a moral code, rooted in belief in G‑d and in the Torah, to the rest of humanity.

3) Vav – Communicating, Teaching, and Empowering

After the letter Heh of the Divine Name, defining the teachings, comes the letter Vav: communicating these teachings, to individuals and to society as a whole.

First, we consider the Jewish education within the communities which closely align with traditional Judaism and with Chassidism. The Rebbe supported, instituted and closely guided many varieties of traditional education: kindergartens, schools, advanced Yeshivot for boys and advanced Seminaries for girls. In this sector his strong support for intensive Jewish education of girls, including the empowering study of Chassidic teachings is remarkable. This contributed to the new role for women as charismatic communicators of Judaism and of Chassidic spirituality.

At this point we consider elements of the Rebbe’s approach to the educational process, as described by Rabbi Dr Aryeh Solomon. His first book The Educational Teachings of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson (Jason Aaronson, 2000) gives a full depiction of themes in the Rebbe’s teachings, such as the essential goodness of the individual, the attainability of goals, that every descent is for the sake of a subsequent ascent and so on, all carefully analyzed in a remarkable way. His recent book Spiritual Education, the Educational Theory and Practice of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson (Herder and Herder) focuses on the Rebbe’s philosophy of education, such as his spirit of inclusivism, including every child or person, however much that individual or group might seem disadvantaged, with an amazingly positive view of each individual and each situation. As Solomon puts it: “Every encounter is an opportunity for education.” Further, he says, according to the Rebbe, education transforms the person, and gives him or her the goal to transform the world, to make it a world of good.

Together with the education in the Lubavitch school/Yeshiva/Seminary system, came the structures of informal education which the Rebbe set up, such as Gan Israel, the holiday camps, and the children’s club Tzivos Hashem.

Then we go beyond the traditional community, to the Jew in today’s acculturated world. This kind of engagement and activism began under the Rebbe’s aegis even before he became Rebbe, with the activities of Mekos L’Inyonei Chinuch and Machaneh Israel. In the mid 1940s he set up the Wednesday Hour program in which Jewish children in public schools would receive Jewish instruction from Yeshiva or Seminary students. Later came the emphasis on the ‘Torah study campaign’ and eventually the Rebbe’s thrust to set up Chabad Houses as centers of Jewish inspiration and education. The creation of Chabad Houses carrying the Rebbe’s educational ethos intensified in the 1980s and continues to flourish, thirty years after his passing, with new Chabad centers being founded wherever there seems to be a possibility and a need. Important recent ventures carrying Jewish education to broader reaches in the general community round the world are the C-Kids and C-Teens.

Another vital educational format going back to the earliest years of the Rebbe’s leadership is Campus Outreach. Today Chabad on Campus serves students and faculty at 500 campuses, with 284 permanent campus centers.

Further dimensions include every kind of adult education, with a special thrust inaugurated by the Rebbe focusing on Senior Citizens, and of course the widely famed Aleph Institute working with prisoners, responding to the Rebbe’s urgent concern for the Jewish education and practice of every individual in whatever situation they might be.

This process extends beyond the Jewish community. From the beginning of his leadership the Rebbe was concerned about daily prayer in public schools, which later extended into a campaign for a daily Moment of Silence. This campaign was relatively unsuccessful in the Rebbe’s lifetime but, by the second decade of the 21st century, no less than 34 states require or permit a moment of silence or ‘quiet reflection’, or prayer, to take place in their public schools.4

All of these initiatives led to the institution of the annual Education Day USA, or Education and Sharing Day, celebrated each year on the Rebbe’s birthday.

An illustration of the significance of this for the Rebbe is seen in his letter to President Reagan, Lag B’Omer, 1987:

I was impressed with your meaningful Proclamation of “Education Day, USA” in connection with the Joint Resolution of the United States Congress… Its mention of “the historical tradition of ethical values and principles, which have been the bedrock of society from the dawn of civilization when they were known as the Seven Noahide Laws, transmitted through G‑d to Moses on Mount Sinai” is a clarion call vital to all mankind.

Furthermore, it is particularly gratifying that you use this occasion to bring to the attention of the Nation and the International community the need of upgrading education in terms of moral values, without which no true education can be considered complete.

Consistent with your often declared position, that “no true education can leave out the moral and spiritual dimensions of human life and human striving” you, Mr President, once again remind parents and teachers, in the opening paragraph of your Proclamation, that their sacred trust to children must include “wisdom, love, decency, moral courage and compassion, as part of everyone’s education”. Indeed, where these values are lacking, education is.. “like a body without a soul”.

With the summer recess approaching, one cannot help wondering how many juveniles could be encouraged to use their free time productively, rather than getting into mischief – if they were mindful of – to quote your words – a Supreme Being and a Law higher than man’s.5

It is less well known that the Rebbe wrote a letter to Mrs Thatcher after her resignation in 1990, asking her too to play a role in communicating the Seven Noahide Laws to the world at large.

Other educational channels originally encouraged by the Rebbe and which have further developed exponentially, concern use of the Internet for education, as in the wonderful mega-site chabad.org, and more recently the use of Whatsap, Facebook, and Instagram as modes of teaching about Judaism and spreading the Chassidic wellsprings.

4) The Final Heh – The Student Becomes an Educator and Leader

We now come to the final stage. The way the student himself or herself becomes an educator, and in that process becomes also a leader.

One of the images for leadership which the Rebbe used was that of the sun and the moon. The sun has its own light. It shines to the moon, but then the moon is able to shine further, using the light it acquires from the sun. It becomes a kind of leader as well, even if clearly lesser than the sun.

In applying this idea to daily life, one has the sense that each person has qualities of both. In one aspect A is the sun shining to B the moon, who then shines to others. But in another aspect, B is the sun shining to A. Of course, it depends what kind of leadership and in what area of life.

Singing the Rebbe’s Song

In the task to transmit love of Torah, love of G‑d and love of one’s fellow, which becomes the task to transform, elevate and enhance the Jewish world, and then to reach beyond its borders, to the world as a whole – clear leadership is needed, in order to remain true to the source. The ‘moon’ can be inspiring and inspired – but it still needs the sun.

The Rebbe expresses this in his discussion of a passage in the Talmud, Sotah 30b, which has been printed as a Sichah on Sedra Beshallach, the Sedra describing the splitting of the Sea.6

The discussion concerns how the Israelites at the Sea, after the engulfing of the Egyptians, sang the ‘Song of the Sea’ (Exodus ch.15) which has become part of our daily prayers.

The Talmud states that according to Rabbi Akiva, Moses declared or sang the words of the Song, line by line, and the Israelites responded to each line with a short refrain which was unchanging: ‘I will sing to G‑d’. Rabbi Eliezer said that Moses sang the Song line by line, and each line was repeated by the Israelites. Rabbi Nechemia said that Moses and the Israelites all sang the whole song together. The question is, how did the Israelites know what to sing? Rashi on the Talmud suggests that the Israelites knew through Ruach Hakodesh, the Holy Spirit. In other words, they were inspired.

We can see this as the full achievement of Moses’ leadership: he enabled his followers, the Jewish people, to be inspired themselves, so that they knew with the Holy Spirit exactly what words to say.

The Rebbe points out in his discussion, that while indeed, according to Rabbi Nechemia, the Israelites had inspired insight – it was Moses who set the words of the song. Leadership on the part of virtually every individual is vital to the Rebbe’s project, and as mentioned earlier, as has often been said, the Rebbe created not followers but leaders. But at the same time, they have to be focused on the Rebbe’s song in order to keep to an authentic route.

We see this in a very clear way in the institution of Shluchim and Shluchot. In an astonishing way, they are empowered, the women as well as the men. They are charismatic leaders. They have the power of the second letter Heh in the Divine Name. But at the same time they seek to be faithful to the original Yud, the central definition of the goal of Chabad-Lubavitch in the world, and of the first letter Heh, which defines it in clear terms. This protects them from falling into a confusion of voices and objectives. As an emissary of the Rebbe, each man or woman is an individual, and brings his or her own special approach, creativity and unique flavor. But at the same time there is a sense of unity of direction and of goal.

Lamplighters – The Rebbe’s Leadership Today

This having been said, it is amazing to consider the remarkable spread of Chabad Houses, most of them established after the Rebbe passed away. One estimate suggested 4,900 Chabad-Lubavitch emissary families, the shluchim and shluchot, who operate 3,500 institutions, in over 100 countries and territories, with some activities in many more.

It is clear that the concept of Shelichut is heavily dependent on the Rebbe’s unique empowerment of womanhood, since the role of the Shliach and Shluchah in any district is to create a center point of a living Jewish family expressing the core spiritual values of Judaism.

A favored image used by the Rebbe is that of the ‘lamplighter’. In times gone by, the street lamps would be lit by a lamplighter, who would go to each lamp and ignite it. In the same way each Jew and certainly each Chassid is expected to be concerned to light the flame of others.

An example of the kind of leadership the Rebbe imparts to his followers is seen currently in the Ukraine. Several families who I personally know in London have children who are active in the Ukraine. When the invasion began, at first many of the Shluchim to the Ukraine wanted to stay with their flock. At a later stage, many were persuaded to leave, even though they continued to maintain close contact with the members of their communities. Then the incredible happened, which I was able to witness. A son-in-law of one of the families in my community in Stamford Hill, London, brought his wife and children to stay with his mother-in-law in London. And then: the Shaliach returned, to inspire and guide his community in the crisis of the invasion, and to make sure they have a meaningful Pesach.

We Should All Be Leaders

Is this immenses sense of responsibility unique to the ‘official’ Shluchim of Chabad? Of course not. I was able to see this tangibly myself. Around 1989, at the close of Simchat Torah, the Rebbe was giving out ‘kos shel bracha’ to thousands of people waiting in long lines. (Some people, as soon as the festival had ended, would fly in to New York for the occasion). To most people the Rebbe gave some wine from his goblet. To some, mostly prominent Shluchim, he gave a bottle of vodka.

On this occasion, ahead of me was a friend from London, a Chassidic businessman. As he came up to the Rebbe, the Rebbe gave him some wine and also a bottle of vodka, saying ‘this is for the shelichus’, this is for your mission.

The next day my friend wrote a note to the Rebbe (that is how one would communicate with him, generally), with words to the effect that ‘last night you gave me a bottle of vodka for the Shelichus. I am a businessman: so what Shelichus does the Rebbe mean?’

The Rebbe answered him with a note, which I quote from memory: Every single person is a Shaliach of the Holy One blessed be He.

Each person is an emissary, each person is empowered. As the Rebbe often said: the person who knows Alef and Bais can teach one who only knows Alef; or if he only knows Alef – he can teach someone who doesn’t know even that…

The Rebbe’s goal was that we should all be educators, and in the most positive sense, that we should all be leaders. In that way we manifest together the second letter Heh, completing the entire Divine Name in the world, making this challenging realm a true dwelling for the Divine.

Source: https://www.chabad.org/news/article_cdo/aid/5490737/jewish/Education-and-Leadership.htm