Gathering focuses on serving Jewish communities despite all challenges

EDISON N.J.—On a night that most often showcases the profound growth and success of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, this year’s International Conference of Chabad-Lubavitch Emissaries (Kinus Hashluchim) paused to recognize and draw strength from the many difficulties emissaries meet and overcome in the course of their work. At times, the hardships begin even before a young couple has landed in the community they will call home.

Like the Zakloses of Novosibirsk, Siberia, Russia. The year was 1998. Rabbi Schneur Zalman Zaklos was 24-years-old, newly married to his wife, Miriam. They both dreamed of becoming Chabad emissaries anywhere in the world, with one exception.

“When I was dating my wife, I told her my destiny is to be a shliach,” Zaklos shared during a presentation at the 38th annual conference, held on Oct. 31 at the New Jersey Convention Center in Edison, N.J. She responded: “’I am ready to go … with you anywhere, except Russia.’”

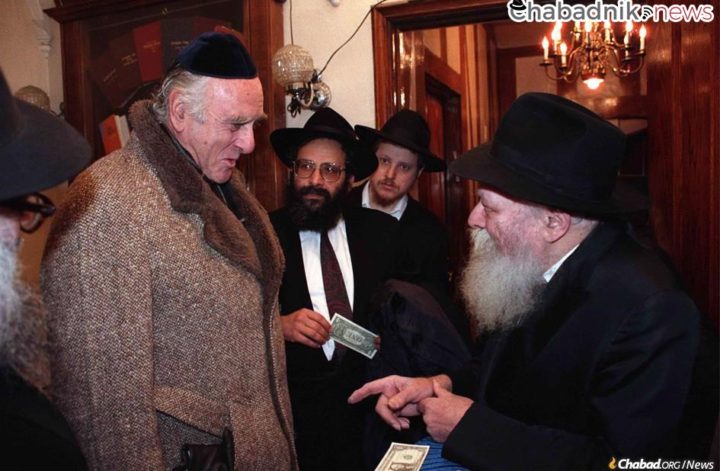

Together, the young couple deemed Russia too far, too cold and too difficult. Still, when friends suggested that they meet with Rabbi Berel Lazar, the chief rabbi and head Chabad emissary of Russia, they took the meeting.

“I told him there’s actually a big city, the capital of Siberia–Novosibirsk,” Lazar recalled. “… His first reaction was, it’s not for him, it’s not for his wife.”

Lazar urged them to at least visit the city, all expenses paid, before declining the offer. This way, he contended, they could know what they were turning down. The Zakloses took Lazar up on his offer and flew to Novosibirsk, the third largest city in Russia, to spend Purim with its local Jewish community. The city was everything they were afraid of—the thermometer read -22 Fahrenheit the day they landed. The synagogue they were shown was a broken shell frequented more often by homeless elements in the city than local Jews, with bathroom facilities consisting of a frozen bucket in the courtyard. The young couple arranged a Purim program to the best of their ability and prepared to leave.

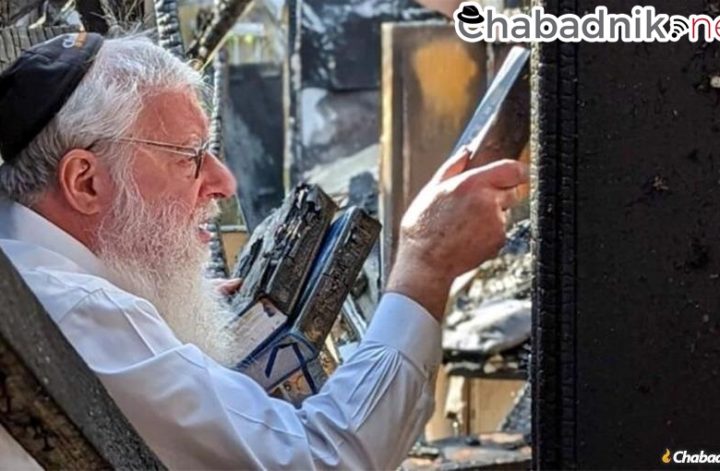

Two days before their return to Moscow, from which they planned to head on home to Israel, there was a break-in at the synagogue. Local thugs broke into the modest prayer room and tore it apart, strewing Jewish books around the room and depositing the Torah scroll on the floor. By the time Rabbi Zaklos got there the thugs were gone, leaving behind antisemitic graffitti threatening more.

“Sure enough, I get a call,” recalled Lazar. “It was the middle of the night and he was frantic.”

Lazar told Zaklos that the local government would not do anything unless there was media attention, so he asked the young rabbi to just show up at the synagogue and show the media what had taken place inside. Zaklos did as he was asked, and before long found himself facing TV cameras and microphones in an impromptu press conference.

“The first question I was asked was if I am the rabbi of Novosibirsk,” Zaklos recalled. At that moment the Conference screens flashed an image of a young Zaklos, an Israeli Lubavitcher Chassid who had gone to Novosibirsk with his wife for nothing more than a short visit, being asked by local Russian media how long he had lived in Novosibirsk and what brought him there.

“I haven’t been living here long,” the archival footage showed him responding. “I’ve only been here a short time, in order to be the rabbi for the Jews here in Novosibirsk.” He then addressed the municipality directly: “You must truly do everything in your power that something like this should never happen again. When something like this occurs in a city, it is terrible and shameful. And the only way to ensure this is by finally having a place where it will be possible to build a large synagogue … .”

Even as the story went viral in Russia, the couple returned to Israel, where they were met with a barrage of congratulations from friends and family on their new position as Chabad emissaries and leaders of the Jewish community of Novosibirsk. One evening a month or two later Zaklos was sitting at the table with his wife.

“I tell her, ‘Listen, everyone in the world has decided and is sure that we are the shluchim to Novosibirsk aside from us,” remembered Zaklos.

“He realized that when he said, ‘I’m the rabbi here in the synagogue and the rabbi here in the city,’ this wasn’t just … by chance,” added Lazar. “This is what the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] was telling him, that this is your [place.]”

The obstacles were many: Siberian isolation, antisemitic sentiment, and most of all, their own fear. Yet it was precisely these setbacks that propelled the Zakloses to accept their positon in Novosibirsk and set about kindling Jewish life in the frozen city, including the 2013 construction of a gleaming 375,000 square-foot Jewish center, a far cry from the dilapidated structure they had been met with.

Transforming Challenge to Opportunity

The Zakloses’ story is not uniquely their own in the sense that the Rebbe taught that particular challenges are given to particular people. G‑d does not place an obstacle before someone if they cannot overcome it, and so the difficulty is itself a sign to dig deeper, persevere and transform the circumstances into a positive.

It’s what Rabbi Heshy Epstein spoke about, too, when recalling the welcome he got when he arrived with his wife, Chava, to establish Chabad of Columbia, South Carolina, in 1987. He met with an influential Jewish business leader in the city named Lee Baker, who told him matter-of-factly to not bother unpacking his bags and go back to New York.

“What I said to him was ‘Thank you for the suggestion, I will take it under consideration and get back to you on that,’” Epstein said. “What I should have said was thank you for your concern … But there’s a Rabbi in Brooklyn who thinks otherwise and he cares too much about the Jews in Columbia for me not to give this my best effort, and he has entrusted me to make his vision real.”

Seven years later, when Chabad of Columbia honored Baker for his ongoing support for their Jewish school, Epstein thanked Baker for spurring him on.

“I reminded him of our first meeting and how he told me not to unpack,” said Epstein. “He smiled sheepishly and said ‘I’m so glad you didn’t listen to me.’”

But the truth, Epstein said, is that he did. The words “don’t unpack” continue to ring in his ears, and each time he faces a challenge today he realizes he needs to double down and continue unpacking.

“Whenever it felt like all this was too much, that unpacking those first few boxes was a big mistake, I” think of those words, he said, and realize “that whatever problems I’m facing are because I still have more boxes that I need to unpack.”

Baker went on to be a great source of inspiration and support to Chabad of Columbia, but Epstein regrets the businessman didn’t live to “see what would have clearly made him happiest of all. From the very office where we had that original conversation 35 years ago, if he were alive today he could look out the window and see the newly renovated Rohr Chabad House at the University of South Carolina, run by the son and daughter-in-law of the young rabbi he told not to unpack.”

The gathered also heard from Rabbi Mendy Sternbach, co-director of Chabad of Lagos, Nigeria, and the first rabbi of Africa’s most populous city; Mr. Dovid Lichtenstein, founder and CEO of the Lightstone Group; Rabbi Ari Laine, co-director of Chabad of Panama; Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, chairman of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the education arm of the Chabad movement; and Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, vice chairman of Merkos and the evening’s master of ceremonies.

Kotlarsky himself has been battling an illness of late, and shared how a few days after an extensive surgery he lay in bed and thought to himself: “What would the Rebbe want from me? What would the Rebbe demand from me being in such a situation?”

The answer, he went on, was clearly to do more, and so he announced a string of new projects that will be launching this year: A new simcha fund, for emissaries making weddings, bar or bat mitzvahs, or celebrating births; a holiday fund to help them with their family’s expenses; a new fund to build 120 new mikvahs; 36 Torah scrolls for emissaries who don’t yet have one; and 360 new Jewish libraries. There will be seed funding for 120 new emissary couples; and a new Israeli desk to assist Chabad centers catering in particular to that demographic.

The push, Kotlarsky underlined, was so that the Jewish people can turn to G‑d Almighty and say: “Look, the world is ready to be redeemed. That we should see the glory of G‑d throughout the world.”