Confronting the challenges of Covid, people from across the spectrum of Jewish life flock to Chabad.

When the world entered the Covid era in early 2020, life moved online fast. At first, it all seemed temporary; then Covid’s long-term impact became clearer. Through 2020 and into 2021, almost every facet of Jewish community life became available online, and many questioned what the post-Covid Jewish communal future would look like. Pundits asserted that many had become comfortable “Zooming-in” from home and simply wouldn’t return to brick-and-mortar synagogues and community centers. But Chabad took a different tack. In the past 19 months, Chabad-Lubavitch centers in the United States alone have launched more than $100 million in capital campaigns, pushing forward with hundreds of new centers and expanding or renovating existing ones.

This optimistic outlook builds on a growth pattern that’s been happening for decades. A 2020 study by urban and societal trends experts Joel Kotkin and Edward Heyman shows that amid a nationwide, universal decline in the number of synagogues since the 2001 U.S. Synagogue Census—a 29 percent drop—Chabad has been an outlier, experiencing threefold growth. During the same time frame, they found that the number of Chabad synagogues in the United States had gone from 346 to 1,036 with centers now in all 50 states—this number excluding Chabad on Campus chapters, mikvahs, schools, youth centers and Chabad Young Professional communities.

“When Covid started, you already had a trajectory, which to a certain extent, carried Chabad forward and exacerbated the declines that the other movements were experiencing,” Heyman explained in an interview with Chabad.org.

The physical centers reflect Chabad’s interpersonal engagement: Pew Research Center’s 2021 study of Jewish American life finds that two-in-five Jewish adults (38 percent, or 2.2 million people) report engaging with Chabad-Lubavitch (16 percent of those polled participate “often” or “sometimes,” 21 percent reported participating “rarely”). The Pew data also shows that Chabad attracts a diverse population—more than half of all participants personally identify as Reform, Conservative or unaffiliated. A more detailed 2014 Miami Jewish community study echoed the nationwide trend, finding that 50 percent of Jews under 36 were active with Chabad.

This trend of increasing engagement with Chabad only accelerated during the Covid pandemic. As early as March, 2020, when shops, offices and restaurants were beginning to shut their doors—some permanently—and synagogues were canceling in-person services and classes, Chabad centers started adapting quickly, utilizing their decades of experience pioneering Jewish life on the internet. Tens of thousands of children began logging on to Chabad Hebrew schools, and Chabad rabbis and rebbetzins offered a steady stream of online classes and kids activities, using their creativity to improvise virtual twists of anything that didn’t require in-person gatherings.

Human Interaction Is at the Heart of Jewish Life

But this virtual shift was always just a stop-gap measure. For Chabad emissaries around the world, who are gathering in New York this week for the 38th annual International Conference of Chabad-Lubavitch Emissaries (Kinus Hashluchim), it was obvious from day one that Zoom and other online platforms could never take the place of real, in-person human interaction—the type of active Jewish life that had sustained the Jewish people for millennia. At the first opportunity, they knew that real life would have to resume. Even when indoor spaces were shut, Chabad focused on safe opportunities for physical engagement, whether outdoor prayer or social events, or having a socially-distanced coffee with the rabbi in a driveway.

As the world eases into a post-Covid routine, with rising vaccination rates and falling Covid cases, people are increasingly turning to social, communal engagement, and Chabad is well-equipped to welcome them. Even as Chabad emissaries were scaling-back physical activities, many were embarking or pushing forward with construction plans, actively preparing for better times they were sure would follow.

“We knew that things were going to rebound,” says Rabbi Shmully Levitin, co-director of Chabad Young Professionals of Hoboken and Jersey City. He and his wife, Esta, had been operating out of their family home with a vision to someday purchase a dedicated space for their programs. A year ago, the couple discovered that it would be needed sooner.

“During Covid, we realized how critical the need for this space was,” says Rabbi Levitin, who moved to the New Jersey side of the Hudson River with his family in 2015. “We kept hearing from our community that it was Jewish life and connection that kept them going throughout the pandemic.”

Despite gatherings that were either canceled or downsized for much of the first months, the Levitins stayed in touch with their community in other ways, holding a wide array of online classes and events, and delivering Shabbat and holiday packages to Jews in the area, including many they didn’t yet know personally.

Esta Levitin had been wistfully eyeing an ideal property in the heart of downtown Jersey City before the pandemic hit, but it came with a price tag to match. Then, as demand for real estate plummeted, so did the value, and the Levitins raised the opportunity with community members.

The response was an outpouring of support, says Greg Edgell, a close friend of the Levitins and a commercial real estate broker who helped Chabad close the deal. “We raised enough to close in three to four days,” he says. “It was a miracle.” Edgell notes that Chabad’s capital campaign attracted donors from across the board—from major backers who regularly engaged with Chabad’s programs to people who had never come before, like some of those whom he recruited to support the project, from family members to clients and colleagues.

“Supporting Chabad is a no-brainer because it is an investment that has the strongest spiritual return,” says Elior Shiloh, another regular member and supporter. “Rabbi and Rebbetzin Levitin open up their hearts and their home to everyone in the community, and their dedication is the spark that enables thousands of young professionals to live a Jewish lifestyle for themselves and their future families.”

Edgell echoes this sentiment, “Their energy consumes you—you just want a piece in it, you want to celebrate Judaism.” When Edgell recently got engaged, he wasn’t sure his fiancée would share his enthusiasm with Chabad. “She was raised in a Reform background,” he says, “but she was cautiously optimistic.” After she went to her first Rosh Hashanah service, she remarked that it was “the most beautiful, resonant Jewish experience she’d ever had. It was an ‘aha moment’ as we build a family.”

Jersey City is home to many synagogues, remnants of a historic Jewish community at the turn of the century. Today, most lay empty, their stately doors bolted shut. “What if people won’t feel comfortable coming back?” Edgell asked Rabbi Levitin as their capital campaign was coming along.

“ ‘Greg,’ the rabbi told me, ‘even if we will have one person come, we have to do this. We will rebuild.’ ”

Today, the first phase of construction is complete, and the center has already hosted a wedding, in addition to regular class and social events. “It has indoor and outdoor space. It’s perfect,” says Esta Levitin. “This center will serve our community’s needs for years to come.”

Serving Both Niche and Broad-Based Jewish Communities

Where Chabad Young Professionals of Jersey City and Hoboken caters to a specific and underserved demographic, at Chabad of East Lakeview on Chicago’s northside—on the shores of Lake Michigan—Rabbi Dovid and Devorah Leah Kotlarsky serve a growing community with many Jewish options.

“We knew we needed a building,” says Rabbi Kotlarsky. “This is where Jewish downtown Chicago is.” The Kotlarskys have been in East Lakeview since 2015, building on the work of Devorah Leah’s parents, Rabbi Baruch and Chanie Hertz, who began offering Chabad programs in Lakeview years before while simultaneously leading Congregation Bnei Ruven in West Rogers Park, several miles away.

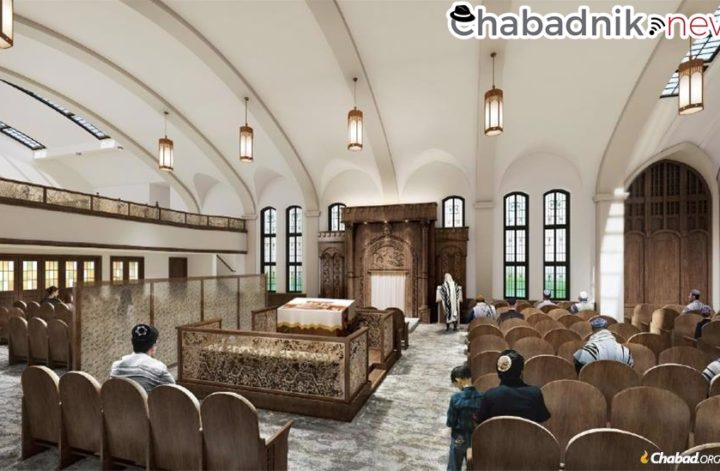

Before the pandemic, they had begun searching for a permanent home for Chabad to replace their rented apartment and small office space, something that could fit a synagogue, preschool and home for the rabbi and family. They weren’t having much success. Then Covid arrived, and they closed their physical location and moved programming to Zoom. Two months later, an offer came their way. It was a former church with a sanctuary, preschool and pastor’s residence. “It was just right,” the rabbi says. “They wanted $3 million. We jumped on it.”

As soon as it was deemed safe, in the summer of 2020 Chabad of East Lakeview began holding socially-distanced, outdoor Shabbat services in a community member’s backyard. “We didn’t miss a week,” says Kotlarsky, noting that prior to Covid, a weekly service was challenging to arrange. It went on for months until a rainy weekend threatened to cut their streak short. “That week, we got the keys to our new building, and we’ve used it ever since.”

Now, the indefatigable rabbi holds services on Mondays and Thursdays as well, and while the Shabbat services attract upwards of 40 people, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Simchat Torah each saw crowds of more than 150 congregants.

Kotlarsky says it’s the building that did it, pointing out that “there’s now a permanence to the experience. People feel a part of something real.”

In their new space, the Kotlarskys have added young-adult programming and will soon open a preschool. “The growth has been amazing,” says the rabbi.

One member, Jaques Aaron Preis, serves as a trustee of the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Charitable Trust. He was so impressed that the trust donated $2 million towards the purchase. His philosophy is simple: “They say ‘If you build it they will come,’ but I say, ‘If you buy it, they will come’—and they’re coming!”

Raised in a Reform household himself, Preis says “there’s an authenticity to Chabad” and their appeal is a nonjudgmental attitude. “They understand that no one will start out doing 613 mitzvot; they focus on each mitzvah without criticizing. They’re so welcoming.”

Preis’s wife Evelyn puts it plainly: “It’s not a diluted Judaism.”

But the new building could not have happened without the broader community believing in the vision as well despite the uncertain times, and more than $500,000 in smaller donations came in towards acquiring the property.

The Resonant Return to Basics

It’s not just in the big cities where Chabad is thriving. As a Jewish demographic shift towards the South and West is underway—what Heyman and Kotkin call “the out-migration of Jews from the big cities”—Chabad is well-positioned to embrace them with open arms.

In 1960, Kotkin and Heyman observe in their study, New York held 46 percent of all Jews living in the United States; by 2020, while the U.S. Jewish population increased by 26 percent, New York’s share had dropped to 25 percent. At the same time, Jews in the South rose from 9 percent in 1960 to 22 percent in 2020; similarly, the share in the West has more than doubled from 23 percent.

The biggest boom has undoubtedly been in Florida, some of it fueled by Covid migration from the Northeast. The general trend of Jews leaving the Northeast has become somewhat of an exodus recently. “While those migration patterns were well-established before the pandemic,” Heyman tells Chabad.org, “we believe the pandemic added impetus to the move out of the large metropolitan areas to smaller cities, suburbs and exurbs.”

“People realized they can succeed in business without being up north,” says Rabbi Pinny Andrusier, co-director of Chabad of Southwest Broward County with his wife, Gitty, in Cooper City. “Florida is the golden land of opportunity; there’s so much potential for personal and communal growth here.”

Andrusier observes that since he opened his Chabad center in 1992, it has come from struggling to find 10 men for weekday services in a trailer and rented storefront to closing, mid-pandemic, on a $4 million, 6.5-acre former rehab center he has begun developing.

“We realized our potential to evolve into a major community center,” remarks Andrusier. The sprawling new Chabad campus will ultimately include both women’s and men’s mikvahs, a dormitory for a teen summer program and a high school for teens from across the country. The main building hosts a synagogue, cafeteria and commercial kitchen. Another building overlooking a lake has been demolished, with the main synagogue sanctuary and hall to be built in its place.

Chabad of Southwest Broward will now establish a preschool to cope with the burgeoning growth of the community. “Other Jewish preschools are full, there’s no space,” he explains. “There’s such high demand due to the influx of people from up north and California that we have no choice but to grow.”

Julia Steiner has watched Chabad’s day-by-day growth in Cooper City since the beginning. The community, she explains, is “primarily non-religious, mostly families coming from Conservative and Reform backgrounds,” but “little by little, people gravitated to Chabad’s trailer.”

Steiner says that Andrusier’s current building plans were initially met with some skepticism, many wanting to focus just on a new synagogue. “It was a long, arduous road” to get people to see the potential Andrusier did, she says, “but the rabbi never looked back. He smiled when people said no and kept looking forward.”

Covid was difficult, Steiner acknowledges, but Andrusier “grabbed it by the horns.” He started with three Zoom classes a day, with Talmud, Kabbalah and a 20-minute noontime chat. Before Shabbat, there was a community-wide Zoom where everyone could wish one another a “Good Shabbos.”

Gradually, she adds, the community went back to in-person engagement, outdoors with masks. “He made sure everyone had a vehicle to remain connected.”

Some communities are still on Zoom, observes Steiner, but Chabad kept the focus on people, not digital platforms, and prepared to go back in a safe manner once vaccination became readily available.

In addition to the influx of newcomers, Steiner sees another factor at play in Chabad’s growth: “Synagogues here are folding and merging with each other; there’s not much left. If you want something, Chabad is the best option.”

Chabad Makes a Big Difference in Small Towns

Within the larger metropolitan areas, Heyman and Kotkin observe that the suburbs are seeing an upsurge of people fleeing the inner urban core. Naperville, Ill., located 28 miles west of Chicago, is home to 148,000 residents and was ranked as “Best City to Raise a Family” in 2021 by Niche. Mirroring the city’s popularity, Chabad Jewish Center of Naperville, led by Rabbi Mendy and Alta Goldstein, has seen significant growth during the pandemic.

Chabad had already closed on a new building just before the pandemic struck, and then, in early March of 2020, their regular activities came to an abrupt halt. “While it was certainly a setback, it gave us the space to renovate while our Hebrew school was on Zoom,” says Alta Goldstein. Before Covid, “we thought we’d only use two-thirds of the building and lease the rest. Now, we need every bit of space.”

With phase two of the center complete, they’ve brought an additional couple on board as youth directors, and their Hebrew school is growing at a significant rate. “Covid didn’t slow us down,” says Goldstein. Phase three, which is projected to bring the costs of the center to $3 million, will include a mikvah, additional classrooms for the growing Hebrew school, a modern sanctuary and a social hall.

Meanwhile, in Bentonville, Ark., famous for being the birthplace and headquarters of Walmart, Chabad completed a $1.4 million center.

“For the first few months of the pandemic, we were either on Zoom or outdoors,” explains Rabbi Mendel Greisman, who directs Chabad of Northwest Arkansas with his wife, Dobi. The Greismans took the opportunity to develop deeper personal connections through one-on-one meetings and smaller in-person gatherings once deemed safe again. As the pandemic waned and vaccinations became widely available, people grew more comfortable and Chabad of Northwest Arkansas’ new synagogue, social hall, classrooms and library were there to greet them.

Joel and Irene Spalter have been attending Chabad of Northwest Arkansas on and off for a decade, as they went back and forth between their Florida home and their children in Arkansas. They didn’t always attend Chabad though.

“We belonged to another synagogue, which became less and less of a spiritual home for us,” acknowledges Irene Spalter. Chabad was a better fit for them, they felt. “We’re used to a more traditional view of Judaism, a deeper view of Judaism,” she says.

“Every good deed counts at Chabad,” says Joel Spalter, “when they ask you to wrap tefillin, you’re accepted with enthusiasm. Nobody asks, ‘How often will you do this?’ ”

While Joel Spalter feels that an important aspect of Chabad’s appeal is its adherence to tradition, Irene points to the warm and welcoming personas of the husband and wife, shliach and shlucha team. “It’s the ambiance,” she says. “If someone is ill or in trouble, Chabad will be the first to assist. I’m amazed by the Rebbe’s teachings; they’re a gift to the world.”

Joel notes that though Chabad never offered virtual Shabbat services, which would be prohibited by Jewish law, that didn’t stop the rabbi from reaching out to people. “Chabad was very cautious. But they get around because people come to them and the rabbi goes out to others, even speaking to them through their window.”

For the Spalters, the new building brings things full circle. After their marriage in 1962, they went to volunteer in Israel for their honeymoon, working at Kibbutz Lavi in the north for 10 weeks, with which they developed a lifelong relationship. When the new sanctuary was being designed, they suggested one of the best-known names in synagogue furniture: Lavi Furniture, straight out of the kibbutz, bringing the touch and feel of the Holy Land into their shul in Arkansas.

Broken but More Determined Than Ever

For two years, Rabbi Levi and Rishi Gurevitch searched for a permanent home for Chabad of Southlake, Texas. Finally, they found an old church up for sale, but it was beyond their means. They kept searching and discovered a more modest building that was, they agreed, more financially feasible. Just as they began negotiations the owners chose to back out and pulled their property off the market.

Devastated, Gurevitch called his father. “You will find something bigger. You will find something even better. You will find something nicer,” Rabbi Chaim Gurevitch promised his son. “Stop worrying so much; just continue doing your holy work.” Days later, Gurevitch’s father was tragically killed in a car accident as he was distributing shmurah matzah before Passover. “Those were his final words to me,” says his son. “That day will stay with me forever.”

Broken but more determined than ever, Gurevitch resolved to double down on Chabad of Southlake’s growth. With the help of his family and community, he went back to the church he’d dismissed as too out of reach and closed the deal. By Rosh Hashanah, barely half-a-year later, Chabad in the Dallas suburb was in its new home, though construction on the $3 million project is still ongoing.

Despite the demographic shifts, California remains a major population center and home to close to 2 million Jews. Chabad’s presence on the West Coast dates back to 1949, when Rabbi Shmuel Dovid Raichik and his wife, Lea, were sent there by the Sixth Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—to “awaken the hearts of our dear fellow brethren.” In 1965, the Rebbe sent Rabbi Shlomo and Miriam Cunin to establish Chabad West Coast Headquarters, and today more than 350 Chabad emissary couples call California home.

Rabbi Menachem and Adina Landa have been serving the town of Novato for a decade in what the rabbi calls “the spiritual desert of Northern California.” They got started without knowing anyone and “hit the ground running,” says Rabbi Landa.

Like everyone, they moved online when Covid came and were soon catering virtually to a wider group of local Jews than ever before. “We knew that this wasn’t a temporary bump; there was a real need that would last long past Covid,” says Landa.

The Landas opened Chabad of Novato in 2012 in their 1,200-square-foot home, soon renting a 1,400-square-foot office space. They knew they’d need to expand their physical center to meet the needs of the flourishing community.

“It wasn’t a matter of if we’d purchase a larger community center,” says Adina Landa, “but when.”

After Rabbi Landa brought Hilda Naam, a 95-year-old Holocaust survivor in his community, to see a property that had come up. “I said to her, ‘Hilda, this is the future of Yiddishkeit,” remembers the rabbi. “She believed in the rabbi’s vision,” says Naam’s daughter, Evelyn Naam.

Naam says that the Landas had been “really generous” to her mother during Covid, a frightening and lonely time for many seniors. “He drove her 100 miles to see her brother” for the first time they’d met in “quite a number of years.” Landa helped Hilda’s brother, 96-year-old Paul, put on tefillin for the first time since his bar mitzvah in pre-war Europe, before they fled to Shanghai.

Hilda had always focused her giving on Judaism and Israel, and told the rabbi she would become the lead donor for the project. The new center will bear her name.

But it was a group effort. Another community member, Gary Cohen, a commercial real estate agent in town, spearheaded the construction while a committee of community members helped Landa raise the rest of the funds needed.

Cohen stumbled upon Chabad of Novato six years ago, after searching Google for nearby Yom Kippur services. And they hit it off.

“I walked in the door, we looked at each other, and it’s been a great relationship ever since. It struck a chord within me.” After the holiday, the rabbi invited him for a coffee, and Cohen never looked back. “I grew up basically Reform in Columbus, Ohio,” says Cohen. In Novato, he found himself “searching for the sweet spot of where I want to worship.” It was Landa’s “genuineness” and embracing attitude that told him he’d finally found it.

The new 11,400-square-foot, $2.7 million center will house a synagogue, mikvah, preschool and youth lounge. “For nine years,” notes Landa, “we had to rent other venues for larger events; our space was too small. Now, we have a place that people can feel is theirs.”

Like so many others during the last two years, Landa was confronted by tragedy when his father suddenly passed away in Canada in February, just as negotiations for the new building’s purchase were underway. “When I got up from the shivah, two hours later, the notary was outside,” says the rabbi. “I knew that this was the way forward and the best way I could honor my father’s memory.”

It’s not that Chabad projects where people are going or which communities are growing better than others, observes Heyman, the demographer, and has thus been able to grow in the last two years. It’s that Chabad simply goes anywhere Jews are. “The Rebbe’s vision of making sure that Jews were never forgotten and never alone, anywhere in the world, and the movement to place emissaries in these environments” means Chabad will more likely than not be there when a family moves into a new town. Whether there was or wasn’t an existing Jewish infrastructure “Chabad became the point of Jewish presence.”

Heyman also identifies a “generational gap” that Chabad has bridged, noting that it is able to attract not only college kids and families but the tough demographic in between. “It’s the same warm and inviting atmosphere they remember from Chabad at college. And they can find a Chabad center wherever they’ve relocated to.”

Ultimately, it’s Chabad’s authentic, traditional perspective that appeals to people. “If you’re seeking tradition, Chabad is open and welcoming,” says Heyman. “It’s the return to basics which people find resonant.”