Earlier this summer, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida paid a visit to the Bal Harbour Jewish community, not for the last time that month. He was there, at the local Chabad Shul, to sign a Moment of Silence bill into law. Like similar bills in several other states, it calls on schoolteachers to institute a moment of silence observed by their students in the first period of each day.

Encouraging school students to focus their thoughts in the beginning of each day — in reflection, introspection, or personal prayer — was a cause passionately championed by the Rebbe. With the approach of the new year, it is about to become especially resonant.

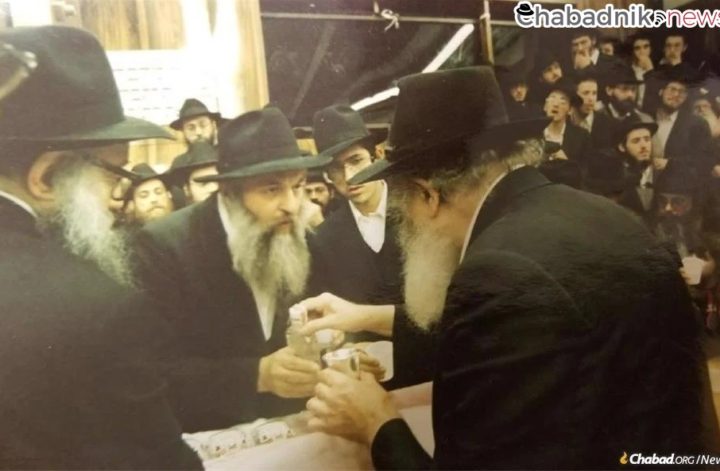

During the month of Elul, as the Jewish people prepared to see off the past year and ring in the new one, the Rebbe would customarily write a letter addressed to the “Sons and Daughters of Israel Everywhere.”

In his letter, the Rebbe would speak to the great spiritual themes of the day, and to our highest hopes for the year ahead. Often, he would point to some distinctive feature on the upcoming year’s Jewish calendar, such as whether it would be a leap year, and explain its special significance.

Invariably, if it was set to be a Shmittah year — the agricultural Sabbatical decreed by the Torah for the Land of Israel, as it will be this coming new year on the Jewish calendar, the Rebbe would make ample reference to it in his letter.

The year 1966 was a Shmittah year, and in his pre-Rosh Hashanah letter, the Rebbe pointed to a curious detail in G-d’s instructions to Moses, in Leviticus (25:1-7), to relay the laws of Shmittah to the Jewish people:

Speak to the children of Israel and you shall say to them: When you come to the land that I am giving you, the land shall be given a complete rest, a Sabbath to the L-rd.

You may sow your field for six years, and for six years you may prune your vineyard, and gather in its produce,

But in the seventh year, the land shall have a complete rest, a Sabbath to the L-rd; you shall not sow your field, nor shall you prune your vineyard.

Shmittah is typically understood as a way to give arable land a rest after working it for six years. So why does the Torah first tell us to let the land “rest a Sabbath to the L-rd,” and then go on to speak of the first six years of sowing, pruning, and gathering produce? Why not just say: When you come to the land, sow your field for six years, but in the seventh year, the land shall remain fallow and have a complete rest. Would that not be the proper order?

This seemingly reverse order, says the Rebbe, is quite deliberate, conveying at the outset a profound lesson for finding order in our lives.

Before settling upon the land, the Jewish people are called to set aside a “Sabbath to the L-rd,” to recognize G-d’s mastery over all things and devote themselves towards a loftier purpose. By putting holiness and spirituality at the forefront of their world, they would ensure that their engagement with the Land of Israel remained infused with meaning and Jewish values. Then, when they went about working the land for the next six years, instead of being swamped by the earthly materialism that occupied them, they would spiritually uplift it.

What was true of the farmers in biblical Israel remains true for us: holding onto holiness doesn’t come any easier now than it did then. Between the daily commute, work and making dinner, there isn’t time for much else. Even those working in religious or communal institutions get tied down by financial concerns, administrative duties, and all the other tediums that come with the day-to-day operation of any occupation or organization. Sometimes, it seems like the odds are against us. There’s only one year of Shmittah, and six times as many regular working years; one day of Shabbos, and six days of work; an hour at the synagogue each morning, and the whole day at the office.

And yet, despite all the commotion, we are called upon to lead our spiritual lives, filled with meaning and purpose — to live a Jewish life. How? The Shmittah order tells us. Putting the spirit of that special seventh year first sets the tone for the first six.

And this is the point of the Moment of Silence, as well: Start the children’s school day right, and the rest will follow.

It is also the essential meaning of Rosh Hashanah. During those first forty-eight hours, we formulate a clear picture of our highest goals, beliefs, and aspirations. Then we can be sure the rest of the year will follow in its elevated wake.

With blessings for Klal Yisrael may we all be written and inscribed for a happy, healthy and sweet new year.