Rabbi Judah Mischel reframes repentance as a joyous journey of self-actualization

The high holiday of Rosh Hashanah that begins this year at sunset on Monday, Sept. 6, is also the opening of the Aseret Yemei Teshuvah, the Ten Days of Repentance, an annual period of self-assessment during which we reflect on all that we thought, said and did in the past year—for better and for worse—and consider who we want to be in the dawning new year.

If we use these ten days properly, we’ll reflect on the times we damaged our connection with G‑d, harmed the people He put in our lives, and missed the opportunities He gave us to actualize our highest, most authentic selves.

Although we will consider the good along with the bad in this annual spiritual performance review, we actively set aside our feel-good-at-all-cost impulses and allow ourselves to experience deep and sincere bitterness and regret for how we have let ourselves and others down. After apologizing and making amends to the people we harmed, we verbalize our regret before G‑d on Yom Kippur and resolve to do better, with G‑d’s help and forgiveness. Yet this is but one crucial aspect of teshuvah.

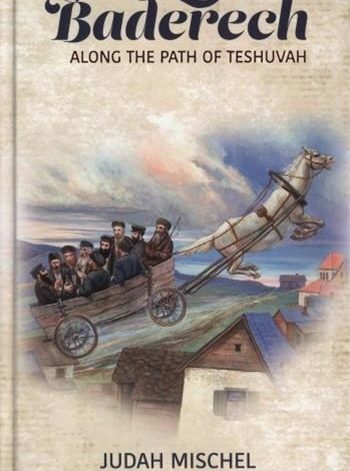

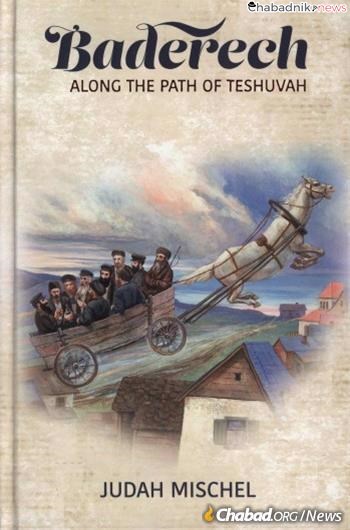

In his timely and elevating new book, Baderech: Along the Path of Teshuvah, Rabbi Judah Mischel convincingly and beautifully demonstrates how teshuvah is one of life’s most positive, empowering, and joyously transformative experiences. At the forefront of our consciousness during these ten days, it’s meant to be an ongoing process of returning to our spiritual roots, improving our behavior and expanding our consciousness that we need to be engaged in throughout our lives.

Drawing on hundreds of teachings and anecdotes from Judaism’s greatest tzaddikim and sages, from Tanach and the Talmud to the 21st century—including a host of Chassidic masters from Reb Zusha of Anipoli to the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—Mischel asserts that teshuvah is not so much a set of actions as it is a path and a way of living. It’s a path to forgiving and forgiveness, a path toward honesty, humility, and sincerity, and most of all, a path to inner peace, engagement with the world, and awareness of the Divine presence in every aspect of life.

As a core principle of Jewish faith, teshuvah is an exceptionally rich and complex topic, and to accommodate its scope Baderech’s 500+ pages are organized into three parts, in which Mischel takes us on a historical and contemporary journey into the world of Jewish spirituality.

The Journey

In Part I: The Journey, the author gives a wonderfully succinct and novel insight into teshuvah:

Teshuvah is a process of both discovery and recovery. Perhaps even more accurately, teshuvah is “uncovery”. . . slowly and effortfully peeling off the coverings that separate us from whom we hope to one day become.

The process of “uncovery,” of removing the character defects that conceal our shining, G‑dly soul, is a spiritual practice at the heart of Baderech.

But as anyone who has made a sincere effort to change for the better knows, making an accurate appraisal of yourself and the ways you need to change is easier said than done. Overcoming your blind spots and rationalizations in order to accurately assess where you are at any moment can be a monumental undertaking. Where to begin and how to proceed?

The Path

This leads to the book’s Part II: The Path, in which Mischel explores and teaches us how to actualize a profound Chassidic teaching from Reb Zusha of Anapoli that was preserved in a foundational work by the Rebbe, HaYom Yom. Mischel starts us along the path by noting that:

What follows was published in HaYom Yom, a collection of daily aphorisms and sources compiled by the Lubavitcher Rebbe in 1944, with the instruction to “live with each day.” In entries covering six consecutive days during the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, the Rebbe shared the following story and insight from Reb Zusha:

Reb Shneur Zalman, the Alter Rebbe of Lubavitch, shared an episode with his grandson and successor, the Tzemach Tzedek, Reb Menachem Mendel: “My Rebbe, Reb Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezeritch, shared a teaching beginning, ‘V’shavta ad Havayah Elokecha — you shall return to Hashem, who is Elokecha, your G‑d.’ ”

He explained that the avodah (service) of teshuvah must continue until Havayah, transcendent Divinity beyond worlds, becomes Elokecha, Your nature, Elokim being numerically equivalent to ha’teva (nature). As we find, “In the beginning, Elokim created the heavens and the earth.”

All of the members of the holy band of disciples of the Maggid, the Chevraya Kadisha, were profoundly stirred by this teaching.

The tzaddik Reb Zusha of Anipoli said that he could not attain the heights of such teshuvah; he would therefore break down the teshuvah process to its components, for the wordteshuvah is an acronym, made up of the initial letters of five pesukim (Torah passages).

Te: “Be sincere with Hashem, your G‑d.”

Sh: “I have placed Hashem before me, continuously.”

U: “And you will love your friend as yourself.”

Va: “In all your ways know Him.”

H: “Walk modestly with your G‑d.”

Over the next 400 pages, Mischel unpacks Reb Zusha’s “five steps” in great detail, and illustrates how through wholeheartedness; experiencing G‑d’s presence; loving others and ourselves; doing so in all our ways; and embracing the virtues of modesty and humility, everyone can be moving towards an ever-higher and deeper life. It’s a fascinating process, and practicing any of its details is sure to make a positive impact on anyone’s life.

Something for the Road

The book concludes with Part III: Something for the Road, Here Mischel delves into the concept of story as crucial to the path of teshuvah. To begin with, we become inspired to change through the stories about spiritual role models.

As a means of strengthening our sense of self and building confidence in our ability to shine forth great light, the Lubavitcher Rebbe recommended sharing stories of the righteous, stating that stories of tzaddikim themselves are Torah, as their instructive insights point us in the direction of how to live our lives, drawing down holiness, G‑dliness, and goodness.” As Elie Wiesel pointed out, we become the stories we hear … and the stories we tell.

While the importance of stories about others is important, it’s how we apply these stories to our own lives that provides the foundation for positive change, says Mischel. Teshuvah is about positively reframing your own life story, every day. As the author concludes:

Real teshuvah is just that: a life of self-discovery and self-recovery, renewal and rebirth. As Rabbeinu Yonah put it: “Yesod hateshuvah, the foundation of teshuvah, is to consider today as the day you were born, the first day of your life.” . . . Being baderech is being “in the process,” of embracing life.

As executive director of Camp HASC, an acclaimed summer program for individuals with special needs, as a mashpia (mentor) at the Orthodox Union’s National Council for Synagogue Youth, and as the father of eight children, Mischel brings a sense of wise experience, warmth, caring, and gentle, positive guidance to every page of Baderech.

Like other popular recent works on Jewish spirituality, including Positivity Bias by Rabbi Mendel Kalmenson, Wisdom to Heal the Earth by Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, and Daily Wisdom by Rabbi Moshe Wisnefsky, Baderech: Along The Path of Teshuvah is a deeply inspiring, practical guide to a more meaningful life that will be of great benefit to anyone, regardless of where he or she is on their spiritual journey.

Baderech: Along The Path of Teshuvah is available at Jewish bookstores and can be ordered online at Mosaica Press.