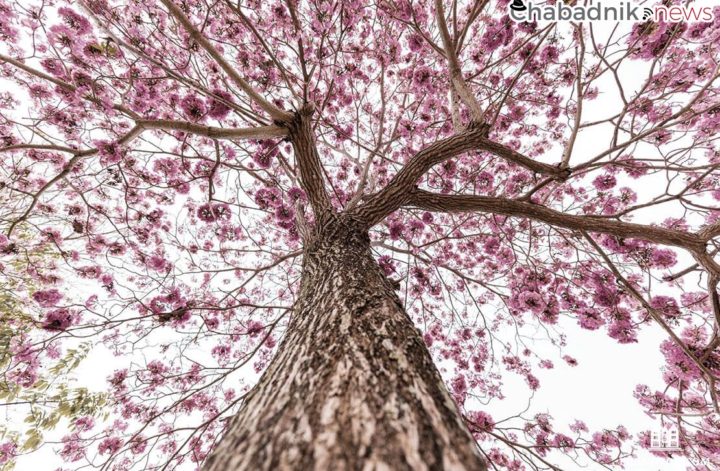

The blossoms have appeared in the land; the time of pruning has come, and the voice of the turtle-dove is heard in our land. Shir HaShirim 2:12

Like all of us, I have tasted Egypt this year. I have borne the burden of worry; I have experienced the lack of control over my work and my environment. My interactions with others have been curtailed; I have felt surrounded by loss. More broadly, I have had to confront the persistent inequities in our society, the inability of so many to feel heard, and most painfully, a sense of distancing from one another so extreme that it feels unbridgeable. In my role as a parent, an educator, a shlucha, it is my job to inspire hope and put a bright face on things, but in my darkest moments, I sense that everything is broken.

Now, there is a vaccine—an exodus from the turmoil. How tempting it is to think that it is only a matter of time until all this is over, like a bad dream—no, a nightmare—that will fade a bit more with each passing day. But what happens when we find that this is not enough to fix what is broken in our lives?

Shir HaShirim, the Song of Songs, is read in many synagogues on Passover, the holiday that falls by biblical mandate in the spring. For all of us that have endured the winter of our lives, the message resonates. How fitting to speak of new love, the emotion that makes us feel that everything is possible. It is an apt metaphor for a personal and national exodus, a grand moment when we leave our misery behind and follow G-d into the barren desert, confident that he will carry us through it all.

But if we read carefully, we will find that Shir HaShirim is not that kind of love song. We will find that this most poignant story has not yet been realized; it has not yet reached its natural end. For the love affair between G-d and the Jewish people is a dance of approach and retreat. Adam and Eve are planted in the Garden of Eden, but there they violate G-d’s command and are expelled. The Jews in the desert, newly redeemed from Egypt, experience revelation and receive the Torah at Sinai, only to betray that gift with the sin of the golden calf. Solomon writes the Song of Songs to mark the dedication of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, the “home” that G-d intends to share with the Jewish people, but as a result of sin and unfaithfulness, that home will be destroyed. And here we are today, praying for deliverance, for the still unconsummated fulfillment of the G-dly vision that preceded creation.

And still, each year, Passover whispers its message of redemption, its acknowledgment of the ways in which love has been betrayed. This is Shir HaShirim asher LeShlomo – the song penned by Solomon of the One to Whom Peace and Wholeness belong.

It was against this backdrop that I decided to explore Shir HaShirim in one of my classes this spring. The midrash has been described as the subconscious of the text of Torah, and having encountered many hauntingly beautiful passages from the midrashic text, Shir HaShirim Rabbah, in the past, I was on a quest for consolation, perhaps even seeking to feel courted, wooed, into a vision of imminent perfection.

But that was not what I found.

The midrash introduces the Song of Songs with a verse from the book of Proverbs: “Have you seen a man quick in his work? He will stand before kings; he will not stand before poor men” (22:29).

It then lists some of the most responsible workers and administrators in Jewish history. First is Joseph, who has been sold into Egypt by his brothers on account of his dreams of greatness, and yet is meticulous about showing up for work on time when he is in the employ of Potiphar, and eventually, Pharaoh. Moses, who speaks to G-d and receives the Torah, is noteworthy for keeping careful accounts of the donations of gold and silver for the building of the Tabernacle; and Solomon makes sure that not a moment is wasted in the building of the Temple.

A love founded on passion alone may be fiery and powerful, the midrash is telling us, but what evidence is there that this passion can be sustained in times of crisis? Joseph, Moses, and Solomon knew that what blossoms in spring was planted in the fall, and will need shade and protection through the summer, that redemption comes in the slow, steady accumulation of promises fulfilled.

“The voice of my Beloved! Behold, He comes, leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the Hills. My Beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag; behold He stands behind our wall looking through the windows, peering through the lattices.” (Shir HaShirim 2:8-9)

We Americans are an optimistic people, a nation of dreamers. But we cannot force a better tomorrow simply by stoking the passions of our idealism. What are our responsibilities—to self, to family, to community, to G-d? What promises must we make good on, even when the moment seems to call for revolution, outrage, radical transformation? What is the work that we must do to rebuild, to make whole all that has become broken?