‘I want the world to hear our stories’

On April 19, Chabad.org first shared with the world the horrific story of Vanda Semyonovna Obiedkova, a 91-year-old Jewish woman who survived the Holocaust hiding in a basement in her hometown of Mariupol, only to perish 80 years later in another Mariupol basement.

Obiedkova’s daughter and family buried her in a public park before escaping with the help of Chabad-Lubavitch of Mariupol’s Rabbi Mendel Cohen. Tragically, Obiedkova’s fate is shared by many more Ukrainians of her generation—men and women whose stories deserve to be told and need to be heard.

Like those of Holocaust survivors Elvira Bortz, 86, and Valentina Levashina, 85, two women whose fates diverged in the spring of 2022.

Bortz, born in Mariupol, can count 38 members of her immediate family murdered by the Germans and local Ukrainian collaborators in October of 1941. She was nearly betrayed by her neighbors before being sheltered by sympathetic non-Jews. After World War II, she lived peacefully in Mariupol until February of 2022. For 50 days, Bortz sheltered under bombardment, together with her 93-year-old husband, sister-in-law and niece, before the family made it to Kiev on April 14, 2022. That she suffered for so long with nearly no food or water in the 21st century haunts her, but she is alive and determined to keep telling her story.

Her neighbor Valentina Levashina, however—like Obiedkova—had a different fate. Levashina, originally from Ukraine’s Poltava, survived the Nazi evacuating to Central Asia. Later, she moved to Mariupol and likewise lived peacefully until February of 2022. On March 28, after a month of sheltering with no medicine and little food, Levashina died in Mariupol.

“Mama said, ‘I can’t survive this!’ ” recalls her daughter, Viktoria, who was later spirited out of Mariupol in a car sent by Rabbi Cohen. “On the last day, there was a massive artillery attack and explosions; you can’t imagine. Mama just couldn’t take the intensity of it; she just died.”

Viktoria wrapped her mother in a blanket, with the help of neighbors dug a pit in their apartment building’s little garden, and buried her.

The terribly familiar circumstances of Levashina’s death and burial gives renewed meaning to Rabbi Cohen’s pronouncement in the aftermath of Obiedkova’s tragic last journey: “The whole Mariupol has turned into a cemetery.”

By now, living Holocaust survivors are all quite old and often very weak. This has complicated rescue efforts throughout Ukraine, but nowhere more so than in Mariupol, a city that over the last two months has for all practical purposes been wiped off the map. It is impossible to get a bus into Mariupol, let alone an ambulance, and those who’ve been able to flee have done so crammed into ramshackle cars dodging heavy fighting.

“One of the biggest tragedies has been the struggle to save the elderly,” says Cohen, who continues to work each day to evacuate families from the hell of Mariupol. The rabbi’s work is supported financially and logistically by the New York metropolitan area’s Syrian Jewish community, which has been actively working on evacuations from Ukraine since the first days of the war. “It’s difficult to locate and move younger people; it is unspeakably more difficult—sometimes impossible—to take out someone old and weak. It’s heartbreaking.”

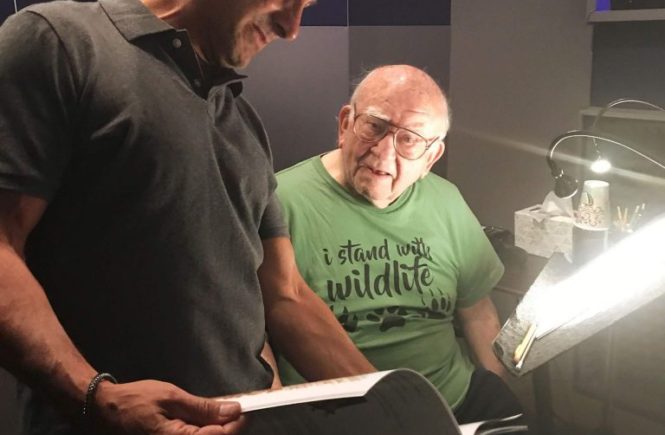

While Bortz did not know Levashina personally, she was friends with Obiedkova. The two had grown up around the corner from each other in Mariupol but lost touch in the decades after World War II. They reconnected about a decade ago at Chabad of Mariupol, after Rabbi Cohen invited the two of them to share their Holocaust experiences with the younger generation.

“Vanda [Obiedkova] was older than me, and she recognized me right away,” says Bortz, recalling their first reunion at Cohen’s center, which housed Mariupol’s only synagogue. “We got friendly again. Even as we got older and both didn’t go out often, we’d talk on the phone constantly. Each time we’d end the conversation I’d say, ‘Vanda, hold on! And she would respond, ‘Elvira, hold on!’ ”

The last time the two spoke was on Feb. 28, four days after the war began, when Vanda called to congratulate Bortz on the occasion of her husband’s 93rd birthday. Days later, Mariupol’s phone lines and cell phone service went dead.

“We ended the last call the same way,” says an emotional Bortz. “But Vanda couldn’t ‘hold on.’ ”

Two Dugouts in 80 Years

Elvira Bortz was born in Mariupol in August of 1935; her paternal grandfather was a rabbi. Prior to the war, Bortz says, the seaside city had a large Jewish population—prominent doctors and lawyers, architects and merchants. Most were shot in Agrobaz, a village outside Mariupol where anti-tank ditches dug by Soviet authorities for the defense of Mariupol were repurposed to kill the Jews by the Germans after their capture of the city. “They say there are 10,000 Jews murdered at Agrobaz, I was always told it was much more, probably 25,000,” says Bortz. “Whole families disappeared, with no one left to even claim their murdered family. Of course, it was more than 10,000.”

When a longtime neighbor informed the Nazis that little Elvira had been overlooked in the roundup, other sympathetic Ukrainians spirited her to another part of town where she was hidden, passed from house to house, for nearly two years. “The Ukrainian Polizei would catch word of me and I’d be moved to another place, a basement, under beds,” Bortz says, “so the [Nazi] SS never got to me.”

In April of 1943 Elvira was concealed, together with a teenage Jewish girl, in an underground shelter dug out of the earth, where the girls remained until August of 1943. By that point Elvira had typhus, and she was pulled out unconscious. She remained bedridden until Mariupol was liberated by the Soviet army in September of that year.

Though Bortz married twice after the war, she always kept her family name as a remembrance for all the Bortzes who were wiped out in the Holocaust. She’d often speak about her war-time experience—in Mariupol’s synagogue, at the yearly memorial service at the Agrobaz murder site—educating younger generations about the unspeakable horrors brought about by Jew-hatred in the modern era. She felt it was the duty of those old enough to have seen the Holocaust with their own eyes to bear witness.

In recent years her niece, Inna, lived in the Bortz family home in Mariupol, while Elvira and her husband lived in an apartment in another part of town. This war, the one Elvira never dreamed she’d have to experience, began on Feb. 24. Four days later, Inna, who’d long helped care for her aging aunt and uncle—Elvira never had children of her own—drove over to pick them up.

“It was only four days into the war, and it was already frightening to drive through Mariupol,” Inna says. It was Elvira’s husband’s birthday, and the elderly couple was brought to Inna’s for what they hoped would be a birthday party and a temporary stay. But things went quickly from bad to worse.

As others have testified, in the early days of March Mariupol lost water, electricity and gas. It was freezing cold outside, and Inna was at a loss as to how she could keep her elderly family members—her mother had joined them, too—warm through the nights and days of endless artillery fire. “They were wrapped in blankets, wearing boots and coats, but it was still freezing,” she says.

When the shelling and bombings got particularly hard, Inna and her mother would head into the basement, while praying their aunt and uncle survived. “My aunt said they both don’t have the strength to go down, and we were simply afraid to harm them going up and down the stairs,” Inna says. “They’re weak people, if they’d break something on the stairs it’s not like we had a doctor to help them.”

In mid-March a family friend, Vitalik, risked life and limb traveling from Kiev to Mariupol to help the family. It was in the nick of time. On March 18, their immediate neighborhood was hit hard by aerial bombardment, with houses on their street transformed into scorched pits big enough to fit a car. As bombs fell Vitalik packed everyone into a car and drove them all down towards the waterfront, safer because both militaries were trying to avoid losing bombs in the sea. Inna recalls passing bodies and burning cars, then looking back towards her old neighborhood and seeing pillars of black smoke billowing into the sky.

“I knew people were sheltering there,” she says. “Now it was all fire and ruins.”

They drove on to another neighborhood, where they settled into an abandoned home. This part of town proved worse than the one they’d left. Vitalik dug a pit in the basement—Elvira’s second dugout in eight decades—and the five of them remained there until April 8, when the home suffered two direct hits from munitions and caught fire. Without a way of extinguishing the flames, they desperately relocated to an unassuming house across the street.

A few days later, they awoke to the blinding light of phosphorus bombs raining down all around them. The fires caused by white phosphorus are difficult to extinguish, and Inna says she saw people trying to pour water on them only for them to grow bigger. The phosphorus destroyed most of the neighboring homes but somehow missed theirs.

As the fighting grew more intense, Elvira and her family were living on their last cans of stewed meat and groats, which they cooked on an open fire into some kind of soup. Water was even more difficult to obtain, and Inna recalls passing unclaimed bodies along the path to the source. Each time she’d return for water the corpses had decomposed a little more.

Time Was Running Out

In mid-April, Ukrainian soldiers told them the neighborhood would imminently be the scene of intense battle and in all likelihood they’d all die. Then, on April 13, they got a visit from 15 Russian soldiers who began quizzing them as to why they were still there, suspecting that they might be passing information on to the Ukrainians. Inna pointed at her aunt and uncle and pleaded that they were only still there because of them. The Russians left after warning the Bortzes to only cook on their open flames between the hours of 6 a.m. and 8 a.m.; otherwise, they’d be marked as a military target.

Time was clearly running out.

“We didn’t want to die,” Inna says, “and we knew if we’d stay another day we would.” Early on the morning of April 14, Vitalik went to retrieve the car, which had been concealed in blankets and somehow still sat in one piece. They then moved Elvira, her husband and Inna’s mother into the car, and Inna got behind the wheel.

“Vitalik got on a bicycle in front of us wrapped in white towels, and we followed slowly behind him with our windows rolled down and also waving white rags,” Inna recalls. “Every 500 meters was a checkpoint, and Vitalik kept shouting not to shoot and that the car behind him had old, harmless people. We prayed and also yelled ‘Don’t shoot!’ ”

Within minutes the car’s tires were blown out by the debris littering the streets. They kept going, passing destroyed buildings, bodies and missile ends sticking out of whatever was left of the asphalt. They did this for 20 kilometers, before Vitalik was able to drop the bike and get into the car. They finally reached Ukrainian territory and then headed to Kiev, where they’ve been ever since.

“I have no idea how we survived,” says Inna. “It was all miracles.”

In Kiev, the Bortzes received financial aid from Rabbi Cohen. It was also in Kiev that Elvira first learned that her friend Vanda Obiedkova had perished in Mariupol.

“Vanda and I spoke about how nice it was that we now live with peace, that our children can’t imagine war like we saw, but here we are again,” says Elvira. “I have no words for the fact that such atrocities could be committed in the 21st century.”

‘Go Where? I Had Nowhere to Go’

Valentina Levashina was born in Stalingrad (today Volgograd, Russia) in 1937 and raised in Poltava, Ukraine, where her father worked as an accountant and her mother a teacher. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Valentina’s parents chose to evacuate from the city immediately, boarding a freight train to Kazakhstan. It was a difficult journey, on which Valentina’s newborn baby sister died of malnourishment.

After the war the family decided to return to Poltava; Valentina’s father died of an illness before they made it there. When Valentina and her mother reached Poltava, they discovered that their home and possessions had been stolen by neighbors or destroyed in war.

Valentina was sent to live with relatives in Kharkov, and in 1959 moved to Mariupol, married and had a daughter—Viktoria. When Rabbi Cohen and his wife, Esther, established Chabad of Mariupol in 2005, Valentina and her daughter began taking part in the revival of Jewish life underway in their hometown. “We became involved from when the synagogue opened,” Viktoria says. “We went for holidays, we kept Jewish customs to the best of our abilities.”

In her older years, Levashina suffered from a chronic heart condition and was aided by Chabad and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s local Hesed, which provided her with a nurse.

“The Jewish community took care of her, materially and morally. We didn’t need anything,” says Viktoria, who lived with her mother in the seaside Primorsky neighborhood. It took only three days for shells to start hitting Primorsky. Like everyone else in Mariupol, the Levashinas had no electricity, gas or connectivity.

“I was alone, the nurse couldn’t get to us of course, and Mama was just lying there,” says Viktoria. “A week in, all her medication was gone.”

The mother and daughter lived on the second floor of their apartment building. Soon enough, their windows were blown out. That’s when Viktoria moved her mother and herself down a flight to a neighbor’s now-empty apartment. They lived there for nearly a month.

“By this point Mama couldn’t understand what was going on. We had no doctors, no help, nothing,” she recalls through tears. The explosions around them kept intensifying. Then came March 28, when the artillery fire and bombs got so intense Valentina couldn’t withstand it. “There was a barrage, and she just died. It wasn’t shrapnel; it was just the intensity of it all.”

That’s when Viktoria wrapped her mother’s body in a blanket and enlisted the help of the few neighbors who hadn’t yet left. They dug a pit in the building’s garden and buried Valentina.

Now alone, Viktoria moved into the building’s basement. When a detachment of Ukrainian soldiers came and told her the building had been hit and she needed to leave immediately because it was burning, she was at a loss. “Go where? I had nowhere to go!”

She remembered a friend of hers who she thought might still be in Mariupol and trekked over to his home. She stayed with him for two weeks, surviving on half a slice of bread they’d split between each other each day. “I felt terrible, I didn’t have anything but he also didn’t have anything. What could I do?”

‘Up to All of Us’

On April 18 Viktoria thought she’d found a way out of Mariupol, but after three days of travel found herself at a dangerous dead end. She didn’t know what to do next. Her mother was buried in a garden. Her home was burned to the ground. Her city was gone. Suddenly, she thought to call Rabbi Cohen.

“I owe my life to the rabbi,” she says through tears. Cohen told her to stay right where she was, and within hours a car pulled up. Utilizing side roads, the driver took her from village to village amid heavy fire overhead, ultimately reaching Zaporizhzhia on April 25.

“Imagine, I was born in 1962 and I have nothing—it’s me and my purse,” Viktoria says. “I hope to go to Israel now. I have no other homeland and no other life. I’m alone in this world. I couldn’t imagine I’d ever live like this. For what? I want people to hear this story.”

Mariupol might be gone, but Cohen knows there are still hundreds of Jewish families left in the city that once was. He’s also been fielding messages from around the world and the list of names to rescue continues to grow. Day and night he works to get them all out, one by one.

For her part, Elvira Bortz says that she’s reached an age where she knows that, thank G‑d, all wars come to an end. The only question is how long it will take.

“That relies on all of us, old, middle-aged and the young.” she says. “We need to do everything in our power to bring about peace in this world.”

Click here to support the Jewish Community of Mariupol’s effort to save lives.

Click here for a prayer you can say and a list of good deeds you can do in the merit of the protection of all those in harm’s way.