Historical Sketches

Events in the Life of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi.

by Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn

Kehot, NY 2014. www.kehot.com

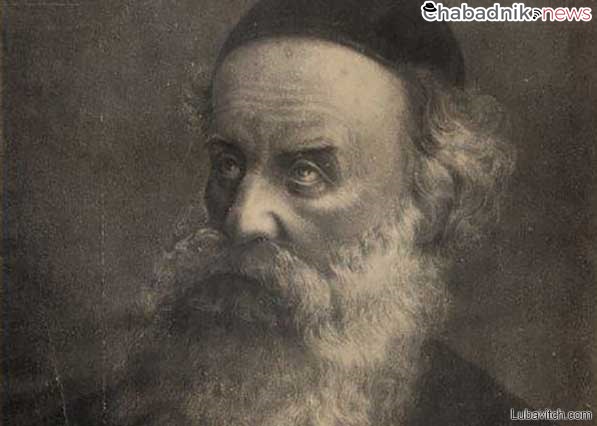

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi

by Nissan Mindel

5th printing Brooklyn, N.Y.:

Chabad Research Center

Kehot, 2002. www.kehot.com

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi

The Origins of Chabad Hasidism

by Immanuel Etkes

Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2015.

The Jewish calendar date of 24 Tevet, corresponding this year (2021) to December 28, marks the yahrzeit of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of Chabad, who passed away in December of 1812.

A few years ago, I reviewed a number of recent biographies of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory for this newspaper. As I read through three biographies of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad movement, known as the Alter Rebbe, I was struck with a strong sense of déjà vu. In countless instances, the features that make the Chabad movement unique today have been present in nascent form from the very inception.

Three Accounts: The Same and Not the Same

These three books cover much of the same ground, often citing the very same source material. Historical Sketches, excerpted from the memoirs of the sixth Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, provides a very personal retelling of events from the unique perspective of a Rebbe. The goal is not to exhaustively document history, but to transmit an appreciation of the times and zeitgeist that shaped the very formation of Chabad movement.

Etkes’ book is written from the perspective of an academic researcher. He confines himself mostly to letters and primary sources such as the Russian archives containing the records of the R. Schneur Zalman’s incarceration. In his quest for an objectivity that has not been tainted by the biases or conjectures of others, he studiously avoids secondary sources. Ironically, this means that he is forced to fill in the gaps in documentation based on his own personal interpretation of events in ways that sometimes border on the bizarre to one who is personally familiar with the Chasidic world. In addition, while he strives to be fair in his analysis of documents and events, he does not have the reverence for his subject that one might expect in reading a biography of a spiritual giant.

For the average reader who has not encountered the Alter Rebbe before, the book that will provide the most useful introduction is the oldest one, Rabbi Nissan Mindel’s Rabbi Schneur Zalman. The foreword of this book, written by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, on the occasion of its first release in 1969, stresses the need for one’s life to be lived in accordance with one’s personal philosophy, and points to this book as one that successfully demonstrates the consonance between the two in the life of the Rabbi Schneur Zalman. For the student of Chabad who seeks to identify the soul of the movement, this book will prove invaluable.

Mirrors of Our Past

The Chasidic movement was born at a particularly turbulent time in history, following the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648-9 and the subsequent false messianic movements. Though these events generated a great thirst for support and healing, they also aroused much fear and caution regarding innovations that might offer false hope and destroy more than they would rebuild. This reflexive skepticism underlay the harsh reception of the nascent Chasidic movement a century later.

With the disbanding of the Council of Four Lands in 1764 as a consequence of the repartitioning of Poland, the major internal governing body of the Jewish people was lost. It was a time of political unrest, characterized by much Jewish migration and Jewish institutional dissension. Each city formulated its own policies, and many Chasidic groups were under renewed attack as some used this opportunity to gain power for their own faction. This period culminated in Rabbi Schneur Zalman being jailed as a dissident and rabble-rouser in 1798 and again in 1800 due to the slander of Jewish informers.

The lack of peaceful cooperation also made Jewish communities particularly vulnerable to inroads from the maskilim, Jewish proponents of the Enlightenment, who attempted to subvert the traditional mores from within by infiltrating the Jewish schools and indoctrinating children with their “progressive” views.

While the details differ, when one reads of the harsh conditions under which the Chasidic movement was born, the image that comes to mind is mid-century 20th century Jewry, decimated by the evils of Hitler and Stalin, displaced and desolate. With the breakdown of the traditional Jewish community, Jews became particularly vulnerable to a whole host of foreign “isms” that further eroded the faithful transmission of Jewish faith.

In our times, the seventh Rebbe made it his life mission to rebuild Jewish faith, peoplehood and community, encouraging and supporting the existing Jewish social and religious infrastructure and building from the ground up where no such infrastructure existed. He inducted shluchim to expand his reach and effectiveness at transforming and revitalizing Jewish society.

Yet in many ways, the Rebbe’s life work can be seen as a revisiting of the model first developed by the Rabbi Schneur Zalman. The founder of Chabad used his wedding dowry to buy land to create farming communities for Jews displaced by the Polish partition. In this way, they would have an independent livelihood and could practice their faith in serenity. Later, when Czar Alexander forbade the Jews from selling liquor to the peasants and ordered over 60,000 Jews to be expelled from their villages by 1808, Rabbi Schneur Zalman organized a collection of funds to help in their resettlement.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman worried no less about the spiritual wellbeing of Jews. Beginning in 1742, many Jewish craftspeople from Poland began crossing the border into Russia twice yearly to participate in the market fairs. They found better financial prospects there than in Poland, and were able to bribe the officials to allow them to immigrate to Russia. Economically, this was a boon, yet the religious infrastructure that had existed in Poland was not present in the Russian towns. Without the synagogues and guilds that had brought Jewish craftspeople together in Poland to pray, study, and otherwise encourage one another to maintain their religious observance, many Jews began a spiritual decline. Rabbi Schneur Zalman sent emissaries to visit the Jews living in the Russian villages to arrange classes in Torah and Midrash for the adults and to set up schools for the youth. Then as now, the role of Chasidut was to give hope and to uplift, to convey a sense of belonging and place in a world that seemed increasingly hostile and alien to the Jewish way of life.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman was a visionary, but also organized and strategic. Based on Russian records of his incarceration, he managed to grow the movement to over 40,000 Chasidim (and internal estimates are much larger). The historical records show that complex regulations were established to manage the great influx of Chasidim to the “court” such as reserving three weeks of the month for new Chasidim and one week for returning Chasidim. There were also regulations to ensure that all visitors had their needs adequately cared for and that those too poor to pay for food and lodging had their costs covered by the court.

Many of his talks were copied and disseminated so that Chasidim could study them on their own Ultimately, as the demands on his time increased beyond what he could personally provide, as stated in the introduction to the book of Tanya, the Rebbe composed a book that could substitute for his personal spiritual guidance by laying out in detail the underpinnings of Chabad thought. In addition, the Rebbe gave detailed instructions to leaders of the various Chasidic communities, so that they could provide additional guidance as necessary.

This was quite a break from the practice of other Chasidic Rebbes, who felt that the average Chasid, relatively simple and unschooled, was not capable of deep philosophical study nor of achieving great level of piety on his own. They taught that the average person could only achieve spiritual transcendence through close adherence to the tzadik.

This level of trust in the Chasid was readily apparent as well in the way our Rebbe led his flock. At a time when the rest of the Orthodox Jewish world saw spiritual outreach as risky and dangerous, at a time when it was felt that no religious Jew could live apart from his peers and teachers and remain unchanged by his environment, the Rebbe confidently sent his Chasidim to all corners of the world, trusting them to internalize his teachings in a way that would enable them to act on his behalf.

Over the years, as the number of Chasidim grew, the Rebbe replaced personal audiences and lengthy private correspondence with more frequent farbrengens, shorter letters, and the distribution of dollars on Sunday morning. Yet Chasidim who immersed themselves in his teachings felt no less of a connection despite these changes.

Although the Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s parents were devoted followers of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Chasidic movement, they were told not to introduce their son to his teachings. Rabbi Schneur Zalman was twenty before he met Rabbi Dovber, the Maggid of Mezeritch, the Baal Shem Tov’s successor, and it was only then that he was inducted into the Chasidic movement. It appears that the Baal Shem Tov trusted him to come to appreciate and embrace Chasidut on his own. And perhaps it was this trust that created within him his trust in the abilities of his Chasidim. In light of this, it is interesting to note that the Rebbe never met the fifth Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Shalom Dovber, (though he did not pass away until the Rebbe was eighteen) and only met the sixth Chabad Rebbe in his twenties. Perhaps his leadership too, needed to be forged by understanding that people could be trusted to seek out truth.

The End is Rooted in the Beginning

When the Rebbe first initiated the tefillin campaign in the aftermath of the 6-day war, scores of Jews in Israel who had never worn tefillin before lined up to participate. The later Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, renowned Jerusalem rabbinical authority, commented on this astounding, unprecedented sight by declaring, “The Lubavitcher Rebbe has faith in Jews.” Indeed, there is no better way to summarize the ethos of Chabad that has remained at the core for over 200 years.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman forged Chabad Chasidut in a way that was very different from the path of other Rebbes. He did not focus on miracle-working, but rather emphasized the miracle of self-transformation. Rather than stressing the role of vicarious personal growth achieved through close personal association with the tzadik,the righteous, he trusted that his followers could take responsibility for their own spiritual development by following his directives regarding study and prayer. He believed that they could study Tanya and faithfully absorb its teachings on their own, not only in his lifetime but through the generations. And undoubtedly, it is this faith in Jews that that has enabled the ranks of Chabad and its shluchim to continue to grow and expand today, even as Chasidim feel the vacuum of no longer having access to our Rebbe’s physical guidance.

Simple faith coupled with intense intellectual exploration; a profound attachment to uncompromised tradition paired with the confidence to engage in the world; devotion to a leader in tandem with an obligation to invoke personal initiative; a love for every Jew and a willingness to sacrifice for both their spiritual and personal wellbeing; a group at once at the heart and apart from “mainstream orthodoxy” . . .

The more things change, the more they stay the same. These paradoxical innovations characterize Chabad today, but they have been there since its inception. For as the Rebbe noted in his introduction to Mindel’s book, in a life well lived, there is no disjunction between one’s philosophy and one’s actions. There is no greater testament to a movement that despite the travails of two of the most turbulent centuries in history, with unprecedented intellectual, technological, and sociological change, it has remained steadily on course.

Dr. Chana Silberstein is educational director of the Chabad House of Ithaca, serving Cornell University, Ithaca College, and the local community. Chana is chair of Ithaca Area United Jewish Community.

Source: https://www.lubavitch.com/revisiting-r-schneur-zalman-the-alter-rebbe/