From her Chicago home, she lavished love and attention to all those who crossed her path

They say you can tell a person’s personality from their couch. Faigy Bassman’s couches feature fluffy cushions with large floral designs on a light background, drenched in sunlight from the largest bay window I have ever seen, and are clearly well-used. Peeking out from behind, one can see a couple of guitars, as well as a colorful array of amateur and professional artwork.

Indeed, spending time at the Bassman shiva home in Chicago—where her husband, eight children, and assorted children-in-law and grandchildren were joined in mourning with dozens of community members—one learns that Faigy lived by lavishing love, care and optimism on everyone she met.

Faigy Bassman passed away on July 8 (Tammuz 29) at the age of 63.

“My mom once came home from a doctor’s appointment without her shoes,” recalls her daughter Leah Emmer with a laugh. “ ‘You’ll never believe what happened,’ she told me. ‘I was waiting outside for my appointment and the most beautiful African-American woman walked by and admired my shoes. The amazing thing is that we are the same shoe size. I begged her to take them—and she did.’ ”

Faigy Bassman and her guitars were a fixture at community women’s events, where she regularly brought joy and inspiration.

Although she did not hold an official community position, she was the address to whom countless people turned with their woes, knowing that she would be there for them 100 percent.

“She was an activist in the fullest sense of the word,” says her son Rabbi Yossi Bassman, an educator in Milwaukee. “She didn’t know the words can’t or shouldn’t. She loved people and loved to help them, caring for them and nourishing them, body and soul. She was an advocate for those in need and a strong voice for those who needed support.”

She was born in 1959 in Cleveland, the youngest child after five boys. Her parents, Jerald and Ruth Schoen, raised her with a strong Jewish identity but not much practice or in-depth knowledge of Judaism.

In search of meaning, she set off to Israel—the only place her parents allowed her to travel to just out of high school. While working on a kibbutz, she met some people from Holland who operated a drug-rehabilitation center. Having learned about the devastation of drug abuse from one of her brothers, who had returned from Vietnam and seen its ravaging effects, she joined them—first in Holland and then in India.

After three-and-a-half years, she returned home disillusioned. Vague notions of enlightenment and harmony were no longer satisfactory. But neither was she impressed with what her friends from home, now college students, were doing.

Together with her mother, she attended a presentation at the local Chabad House in Cleveland. But it turned out to be more than just a class.

The date was 11 Nissan, 1981—the 80th birthday of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. To commemorate the milestone, the Rebbe’s farbrengen was being broadcast over cable, and she was mesmerized by what she saw.

She did not understand the Rebbe’s Yiddish and the topics were not familiar to her, but she was particularly taken by watching and hearing the Rebbe lead the Chassidim in singing “TzamaLecha Nafshi” (“My soul thirsts for You”).

Her soul was on fire.

“I finally found ‘it,’ she would later recall. “And it was there, right in my own backyard.”

She went on to study at Machon Chana in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., and at Bais Chana in Minnesota, where she greatly deepened her Torah knowledge and devotion to a life of Torah and chassidus.

In 1982, Bais Chana held a dinner, and the guest speaker was supposed to be Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. At the last minute, Wiesel needed to cancel, and Faigy was asked to speak in his space, sharing her life journey and how Bais Chana had inspired her.

In attendance was a certain Yaakov Bassman, a successful businessman from Des Moines, Iowa, who had also returned to Jewish observance. Yaakov was impressed by what he heard and inquired about the young woman.

The two married that year, and at his bride’s insistence, Yaakov set aside his business endeavors and enrolled in Yeshiva Tiferes Bachurim, where he remained for five years, broadening and deepening his Torah knowledge.

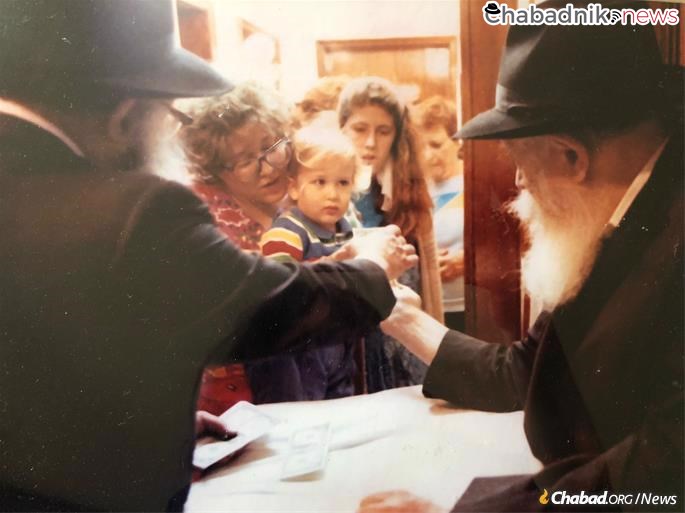

Every Shabbat, along with their growing brood, the Bassmans would make their way to Brooklyn, where they rented an apartment. Faigy would spend time with the children at home, while Yaakov basked in the Rebbe’s presence. And on Sundays, they would queue up with thousands of others to receive a dollar and a blessing from the Rebbe.

After the Bassmans relocated to Chicago in 1991, following a one-year-stint in Des Moines, Faigy—a people’s person par excellence—soon became a one-woman bastion of warmth and love.

A neighbor with a significant stutter and a sweet singing voice recalls how she would beg him to sing, not because she wanted to help draw him out of his shell, she said, but she genuinely loved his singing—and she did.

Never shy, she knew to overstep boundaries. When the principal of a local school fell ill for an extended period of time, Faigy was in the principal’s kitchen every night cooking dinner, cheerfully and patiently, never giving off that she had her own children back home whom she was also caring for.

As her eight children made their way through the educational system, they each brought home a cadre of friends who were made to feel as if the Bassman home was their home. And to Faigy, it truly was.

She loved feeding people, injecting love and care into every bite. “When the bunch of us girls trooped up the steps from the basement in the morning, she had homemade oatmeal waiting for us,” says Esty Perman, a native of Kansas City, who left home to attend middle school in Chicago and often slept over at the Bassman home. “It was the most delicious, heartwarming breakfast I had ever had.”

Perman says she tried recreating the recipe, noting that Faigy was not one for measurements, but with limited success “because the real secret ingredient was her uninhibited love.”

As she believed in people, she believed in G‑d, unconditionally and with unending trust. “Whenever she was told about another’s moral shortcoming,” recalls her son Rabbi Tzemmy Bassman, a Chabad youth leader in Budapest, Hungary, “she would simply reply: ‘Daven [pray] for him.’ ”

Her children chose diverse paths, some entering the rabbinate and others finding fulfillment in different areas. She celebrated their successes and pushed them all to reach out. She did not allow those in leadership positions to become complacent, just as she did not allow the others to absolve themselves from the imperative to share goodness with those around them.

Despite the fact that she suffered chronic pain in recent years, her passing was sudden for all who knew and loved her, sending the entire community into shock—each person feeling they had lost a confidante, a mentor, a sister, a mother and a dear friend.

In addition to her husband, she is survived by their children: Rabbi Betzalel Bassman (Pittsburgh), Leah Emmer (Milwaukee), Rabbi Yossi Bassman (Milwaukee), Moshe Bassman (Chicago), Rochel Meyer (Toronto), Malkie Bassman (Chicago), Rabbi Tzemmy Bassman (Budapest) and Chana Bassman (Chicago); siblings Chuck Schoen and Jim Schoen; and grandchildren.