Remembering Norman Rosenbaum

Thirty years ago, on Aug. 19, 1991, a tragic car accident in Brooklyn, N.Y., sparked what has been called “the most serious anti-Semitic incident in American history.” For four days the Jewish community of the borough’s Crown Heights neighborhood sat in terror, as rioters rampaged through the streets and desperate calls for help were seemingly ignored—events that were described as a modern-day pogrom.

This is an attempt to tell the story of what happened, as framed through the work of the late lawyer and activist Norman Rosenbaum, and his tireless quest for justice for his brother, Yankel, who was murdered during the riots.

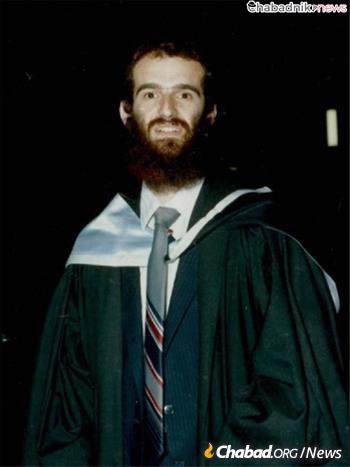

Norman Rosenbaum, a fiery Orthodox Jew from Australia who roused the diverse New York Jewish community to confront the growing danger of anti-Semitism on the streets of New York, shook up the New York political establishment, redrew the priorities of the city’s electorate for decades to come, and gave bold voice to Jews worldwide of the courage to stand up to anti-Semitic violence, passed away on July 25 in Melbourne, Australia. He was 63 years old.

During more than a decade following the brutal murder of his brother Yankel in the Crown Heights riots of 1991, in the words of Dr. Edward S Shapiro, professor emeritus of history at Seton Hall University, it was “the most serious anti-Semitic incident in American history,” Norman Rosenbaum was a fixture on front pages and nightly newscasts for his impassioned speeches, many on the steps of City Hall, in which he demanded justice in the face of entrenched anti-Semitism. Driven with a mission to right the wrongs he witnessed in his lifetime, he was, as one friend recalled, “a man obsessed with justice.”

A barrister by profession, Rosenbaum was a mainstay in the Melbourne Jewish community for most of his adult life. “People were always turning to him for legal advice, general help,” his friend Ephraim Finch, emeritus executive director at the Melbourne Chevra Kadisha, told Chabad.org. “It didn’t matter what it was, he never said no.”

Applying his know-how and dynamic personality, Rosenbaum, working in tandem with Finch, would help ensure that Melbourne’s Jews would receive a proper Jewish burial. “Sometimes, we’d get a call at two in the morning from Rabbi Yitzchok Groner that our services were needed with a tragedy,” recalls Finch. Rosenbaum would dive into action, cutting through legal bureaucracy, and preventing autopsies and other procedures that run contrary to Jewish law.

Rosenbaum enjoyed a warm relationship with his parents, Max and Fay Rosenbaum, and his younger brother Yankel. “His parents were devoted to their boys,” says Finch, “and the boys were devoted to their parents and to each other.” It was this devotion to others, his friends say, that motivated the young man to pursue a life of service to his community, channeling his legal acumen into advocacy for Jews everywhere.

The Day Everything Changed

Everything changed for Norman Rosenbaum on a sunny Melbourne afternoon in August 1991. Halfway across the world and a 14-hour time difference away, his brother Yankel had been doing research at the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City for his doctoral thesis on anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. Returning from a visit to family members in another part of Brooklyn at 11:20 p.m. on Aug. 19, Yankel was attacked by a mob of as many as 20 youths.

Amid shouts of “Let’s kill the Jew,” Yankel Rosenbaum, who stood at 6’4” with a full beard and yarmulka, attempted to take flight. He was overwhelmed by the vicious crowd, who proceeded to beat him, fracturing his skull, and then stabbed him repeatedly. He was rushed to nearby Kings County Hospital after identifying one of his assailants to police, but passed away at 2:25 a.m.

The four days from Aug. 19 to Aug. 22, which became known as the Crown Heights riots, were precipitated by a tragic car accident. At 8:20 p.m. on Aug. 19, a station wagon driven by a Chassidic Jew trailing the Rebbe on a return trip from the Old Montefiore Cemetery in Queens, N.Y., was hit by another car while crossing the intersection of Utica and President Streets in Crown Heights. The station wagon spun out of control, careening into a nearby apartment building and pinning two young Caribbean American children—cousins Gavin and Angela Cato—against the building’s wall.

The streets were packed, as Brooklynites took advantage of the pleasant evening’s weather, a refreshing reprieve after a decidedly hot summer. Within moments of the accident, an angry crowd of several hundred people, largely teenagers drawn from the Caribbean and African-American communities, surrounded the car. The driver and three passengers had leapt out of the car and were attempting to help the children trapped under it, but amid shouts of “Jews! Jews! Jews!” the mob began pummeling them.

Hatzolah, the Chassidic-run EMT service, arrived minutes later. The Hatzolah members tried in vain to work on the two injured children, even as the angry mob beat them, and police repeatedly yelled at the Hatzolah members to “Get out of here! Look at what they’re doing to you!”

City ambulances arrived. Nona Capace, one of the police officers at the scene, found the Hatzolah EMTs assisting their city counterparts with the limited supplies with a “tech/trauma bag.” So focused were the Hatzolah members on saving the children’s lives despite the riotous mob, that they only stopped working on the children after she cursed at them, ordering them to leave the scene, she recounted. The driver and his passengers then left with Hatzolah as city EMTs continued to work on the children.

After the two children were stabilized, they were transported to the county hospital. Tragically, Gavin, just 7 years old, passed away shortly after arriving.

Rumors that the Chassidic Jews had purposefully abandoned the two black children or that the drivers were drunk spread among the growing crowd. Speakers encouraged those gathered to violence with calls to “get the Jews.” Bands of violent youths rampaged through Crown Heights, throwing bottles, rocks, bricks and debris at visibly Jewish houses, cars and passersby.

Despite the sudden, uproarious violence convulsing through the streets of Crown Heights, the police department and New York City Mayor David Dinkins were slow to request an increased police presence, and full mobilization was not completed until 2:40 a.m.

At 11 p.m., Charles Price, a drug addict and petty thief, stood on the roof of a car and began to excite the crowd of some 500 people with calls of “No justice. No peace!” urging bands to “take Kingston Avenue and get the Jews,” referring to the main drag filled with Jewish-owned stores and synagogues.

Among those in the crowd was Lemrick Nelson Jr., a troubled teenager from neighboring East Flatbush. He was found by the police hiding in the bushes just minutes after the mobs attacked Yankel. Nelson was brought by police at the scene to Yankel, who lay languishing on the hood of a Lincoln Continental as blood streamed down his back. Seeing Nelson’s red shirt and baseball cap, Yankel identified him, “Why did you do that to me?” he cried out in anguish. “You in the red shirt!”

Nelson’s clothes were stained with Yankel’s blood, as were the contents of his pants pocket: three blood-spattered dollar bills and a bloody knife with the word “KILLER” etched on it.

‘I’m Here for the Long Haul’

Norman Rosenbaum, back in Melbourne, rushed home from work when he heard the horrifying news of his younger brother’s murder.

Yankel was the last person in the world he expected to die, Norman later told the playwright and professor Anna Deavere Smith. “I mean the fact that my brother could be attacked or die, it just hadn’t even entered my mind.”

As Finch, his friend, recalls it in Australian-tinged Yiddish: “Yankel’s murder took the kishkes, the guts, out of him.”

Yankel Rosenbaum’s body was escorted past Chabad-Lubavitch World Headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in a funeral that attracted some 2,000 mourners as rocks and bottles rained down on them from neighboring rooftops. Some 500 people drove with the hearse to the airport, where he made his final trip back home to Australia.

After shiva had concluded, Norman was tasked by his parents with traveling to New York to bring justice for his brother. He made contact with Rabbi Shea Hecht, today the chairman of the National Committee for Furtherance of Jewish Education and then a member of the Crown Heights Emergency Committee, an entity set up to help in the response to the riots. He stayed at Hecht’s home during his quest for justice.

“I’m here for the long haul. I’m not going away,” Norman told The Jewish Week at the time. Despite a successful law practice in Australia, a teaching position at the University of Melbourne’s law school, and above all, his family back home, Rosenbaum dug in, sometimes spending weeks at a time in New York.

“Norman was an expert on tax law, not a criminal lawyer,” relates Hecht. “But he possessed a deep understanding of how the law worked. He was incredibly sharp.”

Rosenbaum focused on the search for his brother’s killers. Though Nelson had been arrested, he had been only one of as many as 20 people who attacked Yankel. Even though Yankel had been alive and lucid for three hours after the stabbing, he was never questioned by police. Key witnesses were let go without further questioning, and numerous other details were left uninvestigated by the NYPD. Rosenbaum made little secret of his deep frustration and anger with the police and the mayor.

“To Norman, it was inconceivable that the city decided to prosecute only one person,” says Hecht. “They seemed to stop their search for justice after they found only one of many people culpable for Yankel’s murder.”

Norman didn’t stop, regularly speaking at protests and gatherings across the city. Realizing the enormity of what unfolded, Rosenbaum bucked the trend among elected officials and even the Jewish establishment, to relegate the violence in Crown Heights as a “local issue.”

Echoing Rosenbaum’s sentiment, A.M. Rosenthal, the venerable New York Times editor, was one of the few columnists willing to acknowledge the deafening silence

“Some Jewish organizations acted as if Crown Heights did not quite concern them,” Rosenthal wrote just two weeks after the riots, “Their usually ferocious faxes were either silent or blurped out diplomatically balanced condolences to all concerned.”

Instead, Rosenbaum centered the violence, and the loss of his brother’s life, on the bloody truth: the age-old expression of antisemitism once more rearing its ugly head.”

“My brother’s blood cries out from the ground,” he boomed at one event in front of City Hall, intoning the biblical verse after Abel’s murder to indict the city. “His blood is on their hands. And I hope they never, ever forget. My brother was killed in the streets of Crown Heights for no other reason than that he was a Jew!”

Rosenbaum’s frustration was only magnified by the city’s bungled attempt to prosecute Nelson. With a confession, bloody murder weapon and victim identification all locked away, a conviction for Nelson seemed like a done deal.

Shockingly, Nelson was found not guilty in October 1992. In a statement, the mayor, hoping to move on and already focusing on his reelection campaign for the following year, said “I have no doubt that in this case the criminal-justice system has operated fairly and openly.” That evening jurors attended a post-decision victory celebration for the freed man, hosted by his defense lawyers at a restaurant in downtown Brooklyn.

“I am incensed at what’s happened,” Rosenbaum called out at a large gathering after Nelson’s verdict later that week. The miscarriage of justice wasn’t “a black or a white issue. [It] affects every decent New Yorker.”

“It’s going to be long, hard and slow, but we’ll get justice. Let me assure you of that,” he told JTA at the time.

Another point of contention for Rosenbaum was what he saw as lopsided coverage of the riots and their aftermath.

“Norman would often point out how the media equivocated the accident that took Gavin’s life with the murder of his brother Yankel,” says Hecht. “It was deeply upsetting.”

‘It’s a Pogrom! You Know What That Means?’

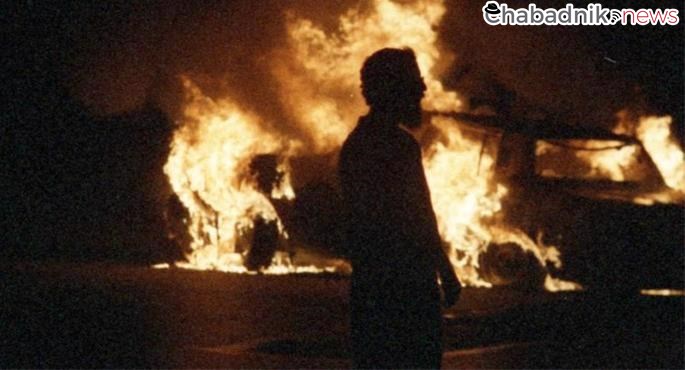

For four days, violent anti-Semitic mobs coursed down the streets of Crown Heights. Angry protests led by outside agitators during the day gave way to chaotic riots each evening. The fear of the Crown Heights Jewish community is palpable in the records of 911 calls made at the time.

On the second evening of the riots, a Jewish woman told the dispatcher how she made her way home with three small children as angry rioters chanted “Heil Hitler!” and “Kill the Jews,” all while police officers stood passively by, observing from the street corners. As she entered her building, bricks and bottles burst through her windows. Shielding the children, she was hit by a rock and a shower of broken glass. Even as she entered, the angry mob began to pound on her door, taking off its hinges until the door was only held in place by the lock.

Taking cover under a table, she frantically called 911.

“You’ve got to get the National Guard,” she told the operator. “I don’t know what you can do. … They’re throwing bottles … they’re breaking stores! It’s a pogrom! You know what that means? It is bad. If we have to wait for the killings, we’re finished. If we have to wait … my door’s broken. I’m not safe in my house anymore. I want to get out. How am I gonna get out of here?”

Records show that she called 911 half a dozen times that evening. Yet despite repeated promises from the operator that authorities were on their way, the cops never came.

Time and again, the Jewish community saw the police stand by—unwilling or unable to act—as windows of Jewish homes were smashed, cars were burned, and Jewish bodies were assaulted

In one particular incident, a group of some 50 people attacked Isaac Bitton, a Chassidic musician, as he walked home with his son Yechiel. Pelted with bricks and stones, Bitton watched in horror as the police stood off on the sides of the intersection. After a brick struck his head, Bitton fell on top of his son in an attempt to protect him. The mob swarmed around the two fallen Jews, pulling the child out from under his father as they beat them. Finally, Peter Noel, a Caribbean American reporter for The Village Voice, ran in to save them from the bloodthirsty mob

As a cavalcade of charlatans and hucksters, attempting to capitalize on the pain of the Cato family, led successive waves of rioters down the streets of Crown Heights, the trauma experienced by the Jewish community lingered. Brokha Estrin, 68, a widowed Holocaust survivor and refugee from the Soviet Union, told her neighbors she could no longer endure what was happening in her neighborhood. Tormented by the traumas of her youth, she leapt to her death from her third-floor apartment, just down the block from the site of the accident.

“The Girgenti Report,” the official fact-finding report ordered by New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, noted that the riots—resulting in 152 police officers and 38 civilians injured, 27 vehicles destroyed and an estimated $1 million in property damage—“exhibited a kind of violence rarely witnessed in New York City since much of the aggression was directed against one segment of the community.”

Yet the general press, set on framing the events in central Brooklyn through the lens of national issues of race, failed time and again to identify the raw anti-Semitism of the riots. Despite, as noted in the Girgenti Report, the single direction of the violence against Jews, papers repeatedly presented the riot not as an anti-Semitic attack, but as a conflict between two sides. Despite it’s jarring departure from the realities on the ground, the morning after the car accident and the first night of rioting, the New York Times wrote “Hasidim and blacks clashed in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn through the day and into the night yesterday.”

Ari Goldman, who covered the riots for The New York Times and is today a journalism professor at Columbia University, wrote about his exasperation with this lack of objectivity decades later in The Jewish Week.

“Over those three days, I also saw journalism go terribly wrong. The city’s newspapers, so dedicated to telling both sides of the story in the name of objectivity and balance, often missed what was really going on. Journalists initially framed the story as a ‘racial’ conflict and failed to see the anti-Semitism inherent in the riots. … When I picked up the paper, the article I read was not the story I had reported.”

Norman Rosenbaum remained doggedly on the case. Over the course of three years since his brother’s murder, he logged some 30 trips from his home in Melbourne to the U.S. Working political contacts in Albany and Washington, D.C., including then U.S. Rep. Charles Schumer, Rosenbaum persuaded Attorney General Janet Reno to pursue a civil-rights case against Nelson.

In 1997, the federal court began a civil case against Nelson and Charles Price, who whipped the crowd into fury at the scene of the accident, for violating Yankel Rosenbaum’s civil rights. Slowly, excruciatingly, a modicum of justice was underway

“Anyone involved in the criminal justice system knows that the pursuit of justice is a life-long struggle,” says Devorah Halberstam, director of external affairs for the Jewish Children’s Museum and an advocate for justice after the murder of her own son, Ari Halberstam, who was riding in a van with other Chassidic boys on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1994.

Only in 2003 was Nelson finally found guilty of Yankel Rosenbaum’s murder.

On the 10th anniversary of the riots, Rosenbaum broke bread with the boy’s father, Carmel Cato, in a ritual meal of sorts they would repeat several times over the years.

“We shared a terrible time in New York history,” Norman recalled in 2016. “It’s important for people to see us meet, so that people see that we’re all part of one community.”

‘This Was Anti-Semitism in America’

Even as he toiled tirelessly for justice in New York, he served as a beacon for goodwill and kindness back home in Australia.

In 2012, he helped launch and served as the director of Beit Rafael in Melbourne, an organization dedicated to bringing patients to and from doctor’s appointments, and providing accommodations and kosher meals for family members visiting loved ones in the hospital for Shabbat.

Despite the pain of his brother’s absence, an extended “numbness” as Norman called it, he remained vigilant in his many duties and advocacy.

Back in New York, Norman’s continued advocacy slowly began to create a shift in the city. In many ways, “The Girgenti Report”—the state’s formal acknowledgement of the riots in Crown Heights—was due to Norman’s advocacy.

Released in July 1993, it sent a seismic shock through New York’s political establishment. Compiled by some 40 lawyers and close to 700 pages, in withering detail it analyzed what went wrong during the riots and the initial trial of Nelson, leveling a critical eye on Police Commissioner Lee Brown, the mayor and District Attorney Charles J. Hynes. More importantly, it definitely set the record clear about the anti-Semitic nature of the riots.

According to Edward S. Shapiro, professor emeritus at Seton Hall university, changes in policing after the riots factored into the NYPD’s rapid and “laudatory response to the events of Sept. 11, 2001.”

When the political and Jewish establishment vacillated on the nature of the riots, Rosenbaum centered Yankel’s murder clearly in the lens of his brother’s unfinished research: an act of anti-Semitism with broad-reaching implications for every Jew.

“Norman recognized that Crown Heights was something larger than Yankel, something larger than Brooklyn,” says Halberstam. “He didn’t let people forget that this was anti-Semitism in America, and that it affected each and every one of us. He knew that the knife that killed Yankel was pointed at every Jew—and he fought for us. He truly was his brother’s keeper.

Predeceased by his wife, Ettie, in 2014, Norman Rosenbaum is survived by his mother and his children—Ari, Yoel, Yoni and Michal—as well as grandchildren.